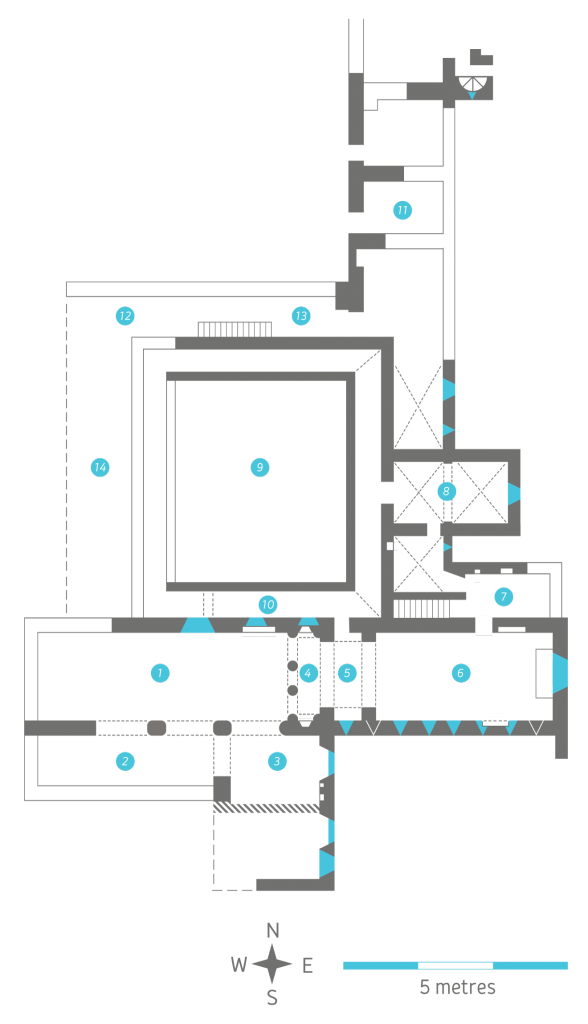

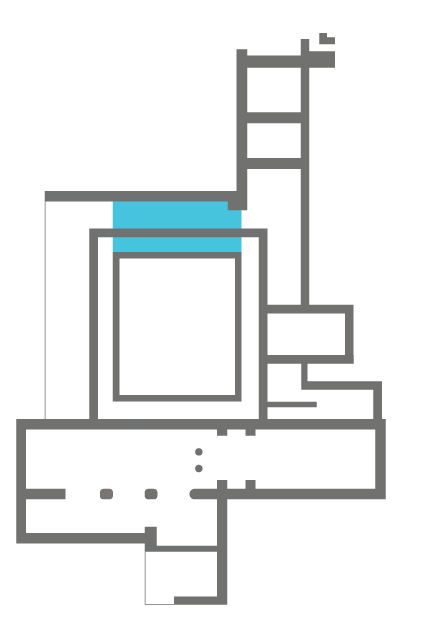

A view of the interior of the nave, with the stone rood screen at its east end, in front of the tower.

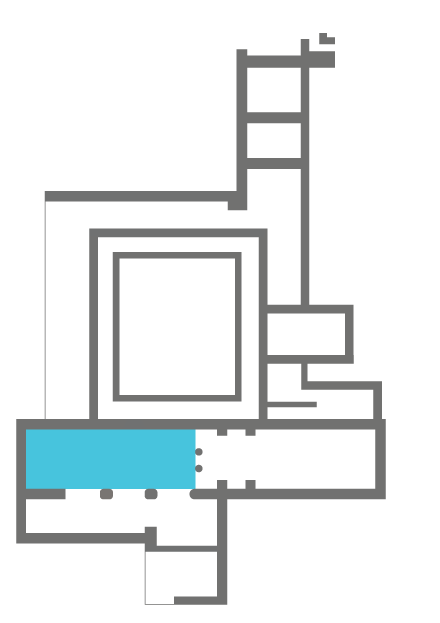

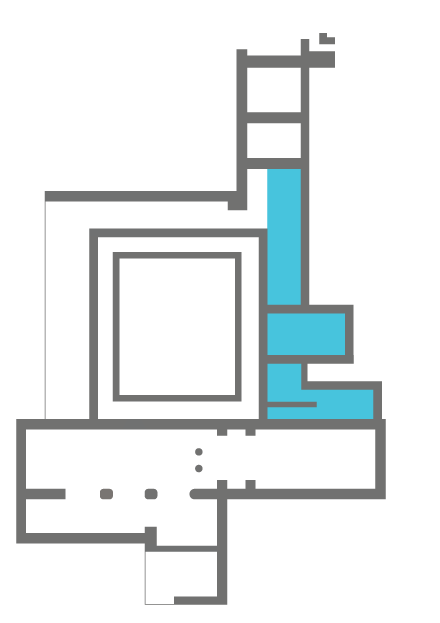

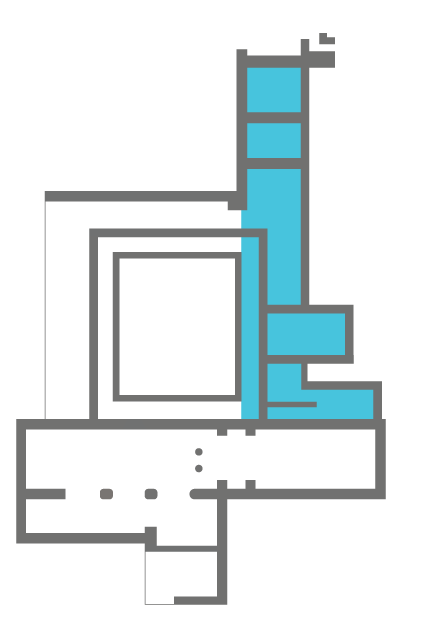

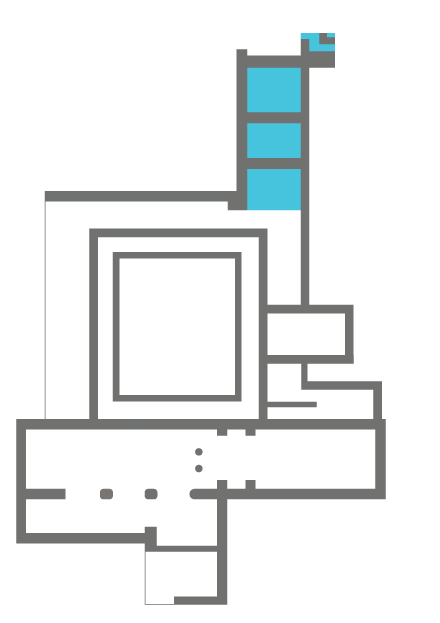

The tower was inserted at a later stage, perhaps when the priory was being restored after the 1414 fire. The tower is supported by pointed arches and groined, fan vaulting.

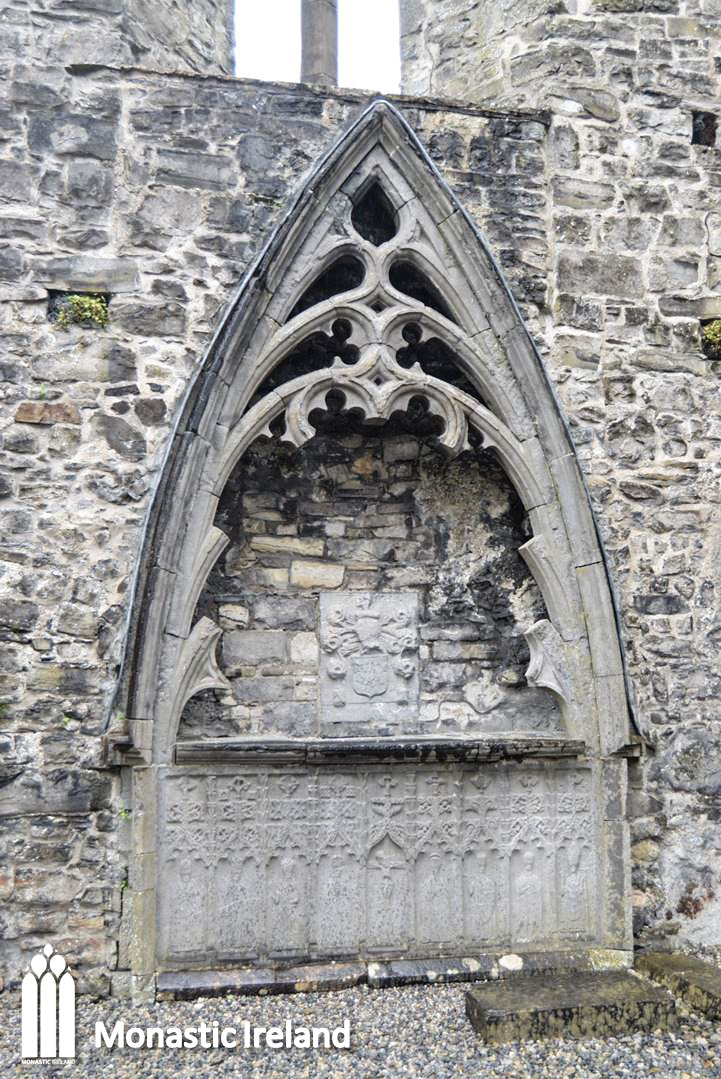

This inserted wall tomb is the earliest of all the funerary and memorial monuments that survive in the church. It was commissioned for Cormac O’Crean and his wife in 1506 and is placed at the northeast angle of the nave, a common position for wall tombs in a mendicant context. It is composed of a horizontal slab and a pointed-arch canopy filled with tracery, only the upper section of which survives, while the front of the tomb is carved into nine panels each surmounted by their own arched canopies decorated with foliage and separated by pinnacles. Within each panel is a carved figure, including a crucified Christ in the central panel, and the Virgin Mary and St John on either side. At each end are a friar and an archbishop; the figure next to the friar looks like a pilgrim, while next to the archbishop are St Peter and St Michael.

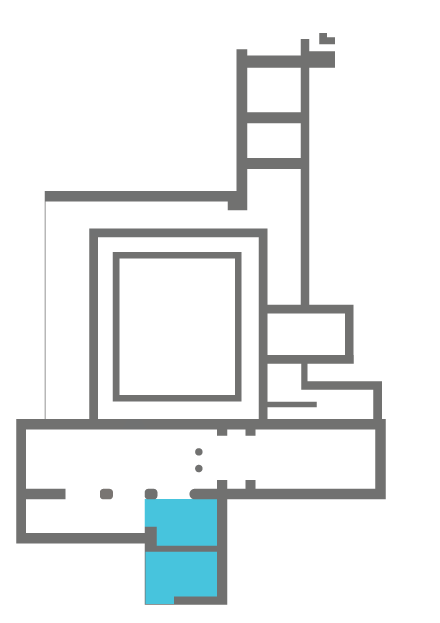

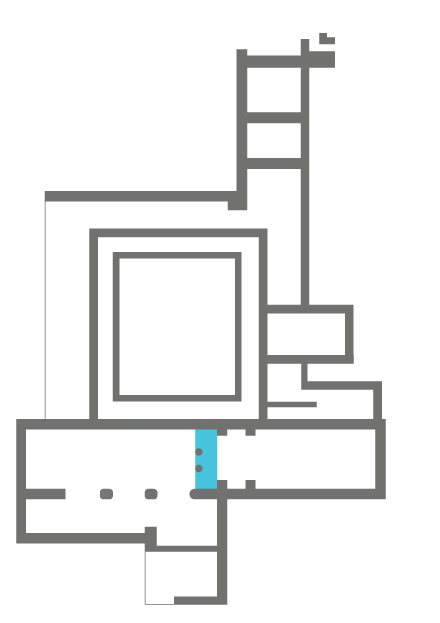

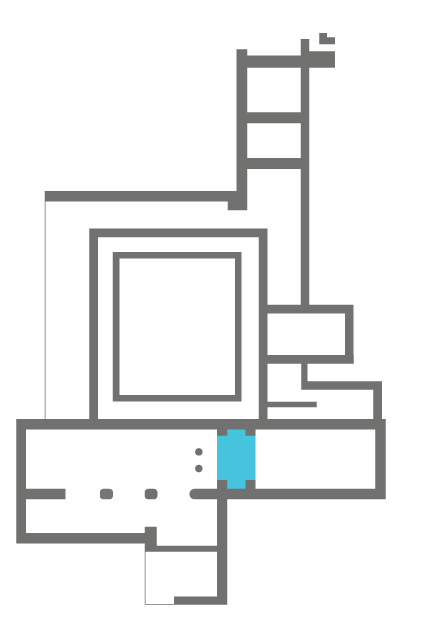

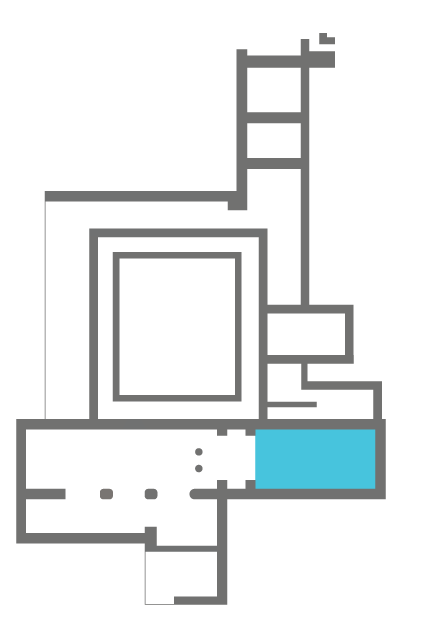

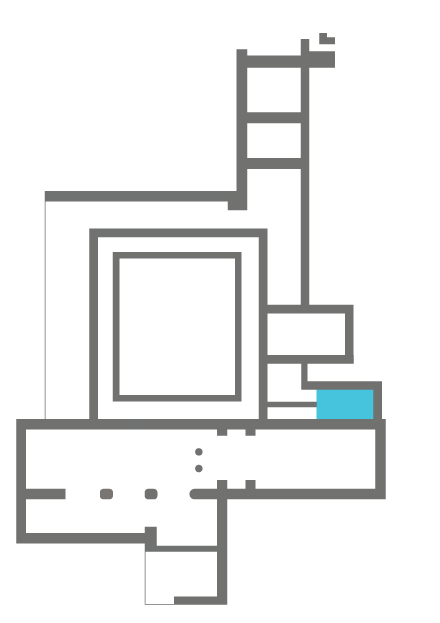

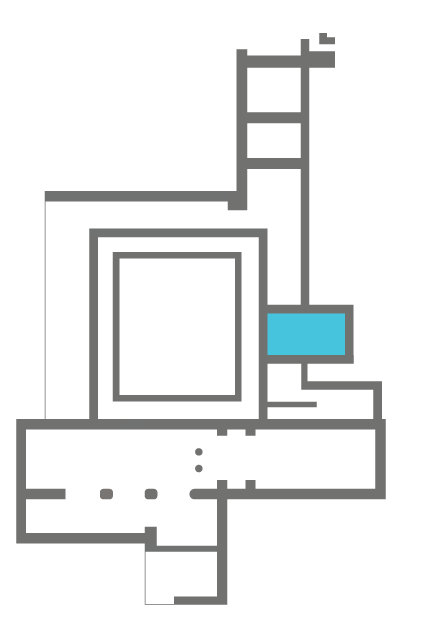

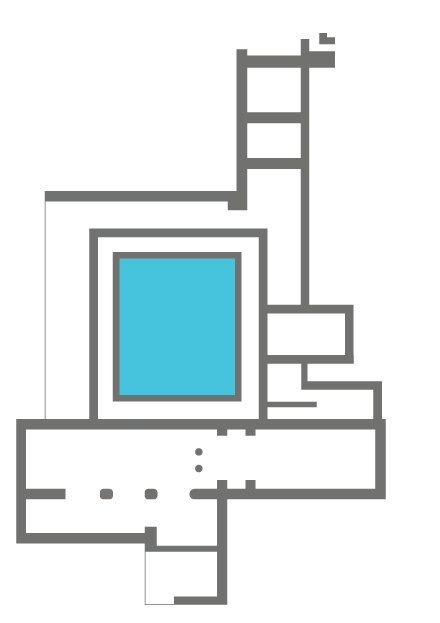

The nave is separated from a lateral aisle and south transept by an arcade of three pointed arches resting on octagonal piers with moulded capitals. Of the transept only the east wall survives, as well as the arch that connected it to the aisle. From the fabric it appears that the aisle predates the transept, and would have itself been an addition to the original single-aisle nave.

The east wall of the transept, showing one of two recessed windows that would have housed the altars of two chapels, with an ambry (recessed cupboard) and a piscina in the space between the two windows. A low, modern wall now sections off the second window, and the ground beyond it has been raised and obscures the chapel recess.

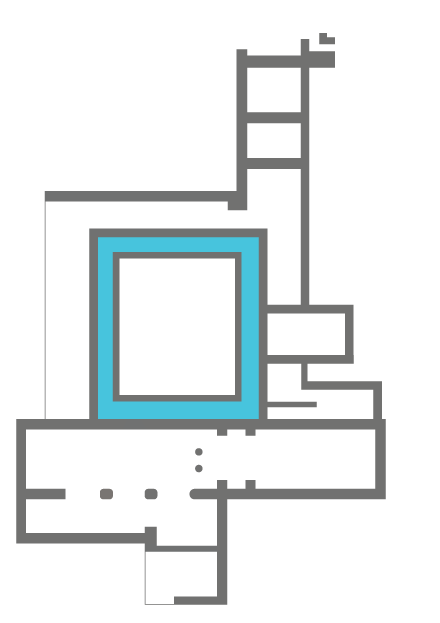

A close look at the foliage stone carving on either side of the pointed end of the corbel that supports the arch separating the aisle from the transept

A closer look at the reconstructed, triple-arched stone rood screen at the east end of the nave. This is the only example of a free standing stone rood screen in Ireland. It was a two-meter wide structure forming a gallery supported by two arcades of three pointed arches, of which the west-most was rebuilt by the OPW in the twentieth century, and which was rib-vaulted.

A look at the engaged columns and springing of the arches and rib vault of the rood screen, with a recess in its south wall. The north wall contains a similar recess, which were perhaps used as chantry altars.

In the north wall of the tower have been placed these three slabs carved with coats of arms, which are probably portions of mural monuments now destroyed. The one on the left bears the coat of arms of Sir Roger Jones of Banada near Sligo, knighted in 1624 and who died in 1625. The other two represents the coat of arms of the O’Creans, a wealthy merchant family of Sligo and patrons of the priory since at least the early years of the sixteenth century, when Cormac O’Crean commissioned the mural tomb in the north wall of the nave for him and his wife.

A view of the interior of the chancel, with two steps dividing the space between the choir where the friars’ stalls would have been and the presbytery, where the high altar stands against the east wall. In the north wall are the door to the sacristy and a pointed recess where a wall tomb would have been, to the south are another recess with a pointed arch that used to contain the sedilia and a blocked recess where the piscina used to be set. The east window, a four-light with reticulated tracery, replaced the thirteenth-century triple lancet sometimes in the fifteenth century, and is very similar to the fourteenth-century south transept window in Kilmallock Dominican priory.

A rare survival in Irish friaries, the fifteenth-century stone altar was reconstructed from the original stones. The front is composed of nine carved panels with cusped ogee heads and foliage carving. The altar table is made up of five slabs, four of which contain a cross and a one-word inscription, spelling out ‘Me Iohan … Fieri Fecit’, which translate to ‘John … caused me to be made’. The one stone that is missing would have certainly borne the surname of the altar’s donor.

This pointed arch, of which the dressing stones were restored by the OPW, was likely were the sedilia used to be, where the friars celebrating mass would sit. The inscription and the carved feature inside the arch are modern additions.

This is the large mural monument of Sir Donogh O’Connor, known as O’Connor Sligo, and his wife Lady Eleanor Butler, widow of Gerald, 16th Earl of Desmond. It was erected in 1624, and inserted in the window nearest to the altar in the south wall. It is composed of three sections, separated by projecting mouldings. The top section, under a crucifix, is a carving of the O’Connor’s arms and motto, framed by the figures of St Peter and St Paul. The central panel of the monument is composed of two arched recesses in which are the figures of O’Connor and his wife, kneeling on either side of a prie-dieu. Below the figures, the lower panel contains an inscription to the memory of O’Connor, who died in 1609, his wife and her daughter by her first husband, who had died in 1623. Below is a carving of a winged hour-glass.

In the tomb niche in the north wall of the chancel have been placed the remains of seventeenth-century grave slabs.

The vaulted room entered through the doorway in the choir’s north wall is the sacristy.

The modern staircase in its west wall leads to the upper floor of the range, where the friars’ dormitories were located, and replaces the original stone stairs. A doorway to the right leads to another vaulted room, perhaps a vestry.

This room was, however, almost certainly the Chapter room. We know this because of its position, its size and more elaborate configuration. It is oriented east west, projecting off the rest of the range, which doubles its size. The room is divided up by a pointed transverse arch, with pointed rubble vaults on either side. The transverse arch is aligned with the east wall of the range, marking the extent of the original thirteenth-century chapter room, which was extended eastwardly at a later stage. The double light window with trefoil heads is a later insertion and replaces a triple-light.

This vaulted room, entered from the sacristy and the first of a succession of three vaulted rooms in the east domestic range, might have been the vestry, where the friar-priest would have changed into his sacramental vestments before mass, although as often in mendicant friaries it is difficult to know with certainty the function of the room.

A view of another vaulted room in the lower range of the east range, located north of the chapter room, but not accessible through it. The north end of the room is broken down, and beyond it are the very slight remains of another few small rooms.

A view of the upper floor of the east range, where one of the friars’ dormitory was located, and possibly the prior’s apartment at the east end. This floor was accessible at least through a set of stairs leading down to the sacristy and from there into the church, and possibly through another set of stairs between the north end of the dormitory and the extension of the east range beyond.

A view of the cloister garth. It is an almost rectangular space, as the west and east sides are about 25 cm longer than the north and south sides. At 15 meters wide it is one of the largest surviving mendicant cloister in Ireland. We can see here how the east side the cloister arcade supported the west wall of the range’s upper floor, the cloister being of the integrated type.

The cloister in Sligo priory is integrated, meaning that the upper floors of the domestic ranges covered the cloister walk. The cloister walk is barrel-vaulted and the surviving arcade is composed of double-shafted pillars with plain chamfered arches.

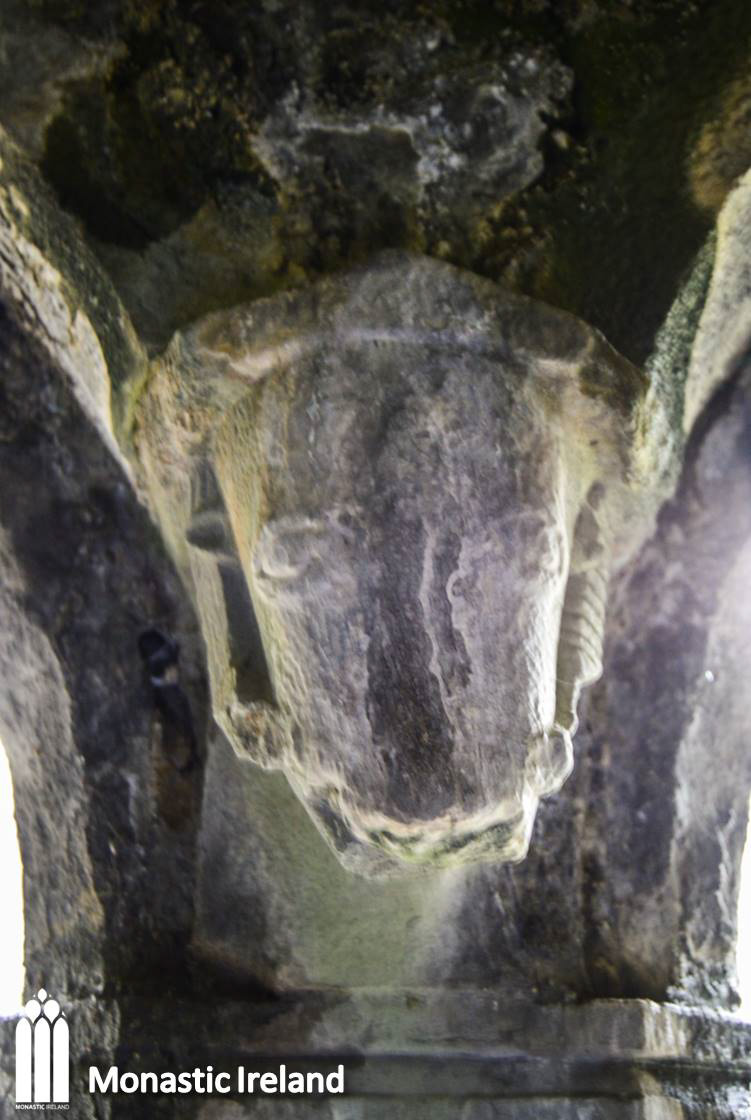

This carving of a ram’s head can be found between two arches of the north cloister arcade.

A closer look at one of the pillars of the cloister arcade. A number of the shafts of the double-shafted pillars were circular and carved into a twisted effect, while most were octagonal columns.

A weathered carved head on a column of the north arcade of the cloister.

A view of the north domestic range, very little of which survives, although parts of the upper floor remains, which corresponds to the section above the cloister walk. A modern staircase has been fitted to access it. The upper floor housed the refectory, which is not an unusual location in a mendicant context.

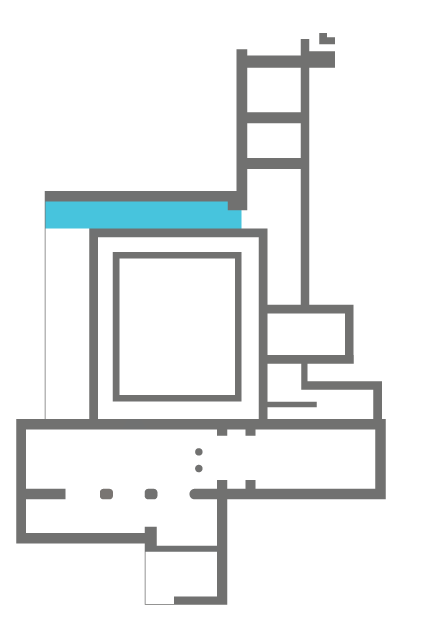

This is the remains of the reader’s desk, or reader’s pulpit, located in the upper floor of the north domestic range, where the refectory would have been. It was set in the thickness of the south wall of the range, overlooking the cloister. It is quite an elaborate structure, entered through three round arches with octagonal columns, and lit by an oriel window supported on a projecting bracket.

A view of the upper floor of the north range, of which only the southern half remains. It housed the friars’ refectory, and beyond it is the long east range housing their dormitories.

A view of the only surviving wall of the domestic buildings projecting off the east range, which might have formed one wing of another set of rooms around a second cloister or court. The upper floor probably housed additional dormitory space.

A view of the remains of the buildings located north of the east range, which might have formed the eastern part of an additional set of buildings around a second cloister, or outer court. Little survives of these buildings, but the lower story was composed of small vaulted rooms, and the upper floor would have probably housed another dormitory. At the northeast angle of the range is the remains of a small square tower, with a spiral staircase that would have led to its upper floor.

A view of the east domestic range looking towards the church, showing the lower vaulted rooms and the dormitory in the upper floors.