A view of the friary from the path leading to its west doorway, a similar approach to what Kilmallock medieval burgesses would have taken to attend services and celebrations in the church.

The west gable of the church, from inside the nave. The simple three-lights with switch-line tracery window is a style that became quite common amongst Irish mendicant friaries. The west doorway is where the laity would have entered the church, standing in the nave to listen to the friars’ preaching, offices and feast days’ celebrations. On the left of the gable wall is the pilaster from where the arcade separating the nave from the side-aisle would have sprung. You can also see the base of one of the arcade’s cylindrical pillar, as well as a few sections of these pillars lying around the nave.

A view of the south chapel and its large five-light window with reticulated tracery, from outside the priory, with the choir to the right and the nave to the left.

A view of the south chapel/transept, south window, a five-lights with reticulated tracery, which appeared in England in the first decade of the fourteenth century, and which, along with other decorative details in the south chapel, suggests that it was the work of a mason trained in England.

A view of the south chapel, or south transept, from the nave. It is likely that this structure was planned out from the beginning, and belongs to the same phase of construction as the choir and the nave. However, the great quality and up-to-date decorative sculptural motifs it features suggests that it was funded by one wealthy individual, perhaps Maurice Fitzgerald, 1st Earl of Desmond (d. 1359), and that it was realised by a mason – or group of masons – trained in the west counties of England.

A close up of the capital of the column supporting the arcade in the south chapel, decorated with ball-flower ornaments, characteristic of the first half of the fourteenth-century decorated style found in the West of England.

A view of the wall niche in the east wall of the south chapel. This niche probably contained a statue, perhaps of the virgin Mary. Indeed these chapels or ‘transept’ in mendicant churches were often dedicated to the Marian cult, and called ‘Lady Chapel’.

At each springing of the niche’s arch are two figurative carvings probably representing the patron who funded the construction of the chapel – perhaps Maurice Fitzgerald, 1st Earl of Desmond - and his wife. Like the capital of the chapel’s arcade column and the tomb niche, the niche’s arch is decorated with ball-flower ornaments.

One of two tomb niches in the south wall of the south chapel, but the only one where the decorative carvings survive along the pointed arch. Here again the use of the ball-flower decoration point suggest that the same mason or masons, trained in the west of England, executed the work, under the patronage of a wealthy patron, perhaps Maurice Fitzgerald, who was made 1st Earl of Desmond in 1329 in Gloucester, where this type of ornament would have been found in the south aisle of the Cathedral for example.

A view of the crossing tower from the nave/side-aisle. The tower was inserted in the fifteenth-century. Its slim and tapered frame is more commonly associated with Franciscan towers. Through its tall and narrow arch, the laity assembled in the nave would have caught sight of the high altar and partaken – at least visually – to the sacrament of the Eucharist. There are three original tomb niches in the north wall of the nave, perhaps of benefactors who help fund the construction of the church.

Another view of the crossing tower, from the choir. The similarity of the tower to that of Claregalway friary, erected in 1433, has led some to suggest that the same masons were involved in the construction of this tower.

A view of the great east window in the choir of the church. It is a group of five graded lancets under a moulded pointed hood with stiff leaf carvings at the stops. Although it could have been considered an outdated form by the end of the 13th century, its sculptural detailing (moulded arches, slim chamfered mullions - the vertical divisions of the window - terminated in moulded capitals, stiff leaf carvings) makes it an elaborate work displaying skills and a quality of execution similar to the decorative work in the south chapel.

Mural tomb in the north wall of the choir. This is considered the most important position in the whole church, in the sanctuary, close to the high altar. It is usually reserved for an important patron, if not the actual founder of the priory. It has been suggested that this tomb was perhaps commissioned by the Fitzgerald family in the early fourteenth-century, and might belong to the same program of patronage as the south chapel. The engaged shafts on each side of the tomb terminate in a carved head, though the one on the left is particularly damaged. The pattern of circles with alternating integrated flame-motif on the lower section of the tomb is similar to a pattern found in the nearby Franciscan friary of Buttevant.

A view of the east windows and the windows in the south wall of the choir. Although the tracery is gone, the very small sections that remain at the top of the pointed arches suggest that they would have been two-lights with switch-line, of a similar type found in the east wall of the south chapel.

A view of the east range, from outside the priory. The east range would typically house the chapter room, and perhaps a day room or calefactory, where a fire would be kept in the winter months and friars could gather to warm themselves up. In Kilmallock this would explain the presence of a large fireplace in that room.

The presence of large fireplace and circular oven projecting from the wall suggests that the kitchen was located in the east range – an unusual location - although it is possible that the oven structure was a later addition.

A view of the interior of the east range. It was internally divided into a succession of three rooms. The middle room was the largest and probably the chapter room, where friars would gather daily for the chapter meeting. The importance of this room is marked by the presence of three large three-light windows, now blocked (on the left hand side of the picture). The room at the western extremity, now considered to have been a kitchen because of the presence of circular oven projecting off a large fireplace in the east wall, could have originally been a day room or calefactory, where the friars could gather to warm up in the cold winter months. Above these rooms was a dormitory.

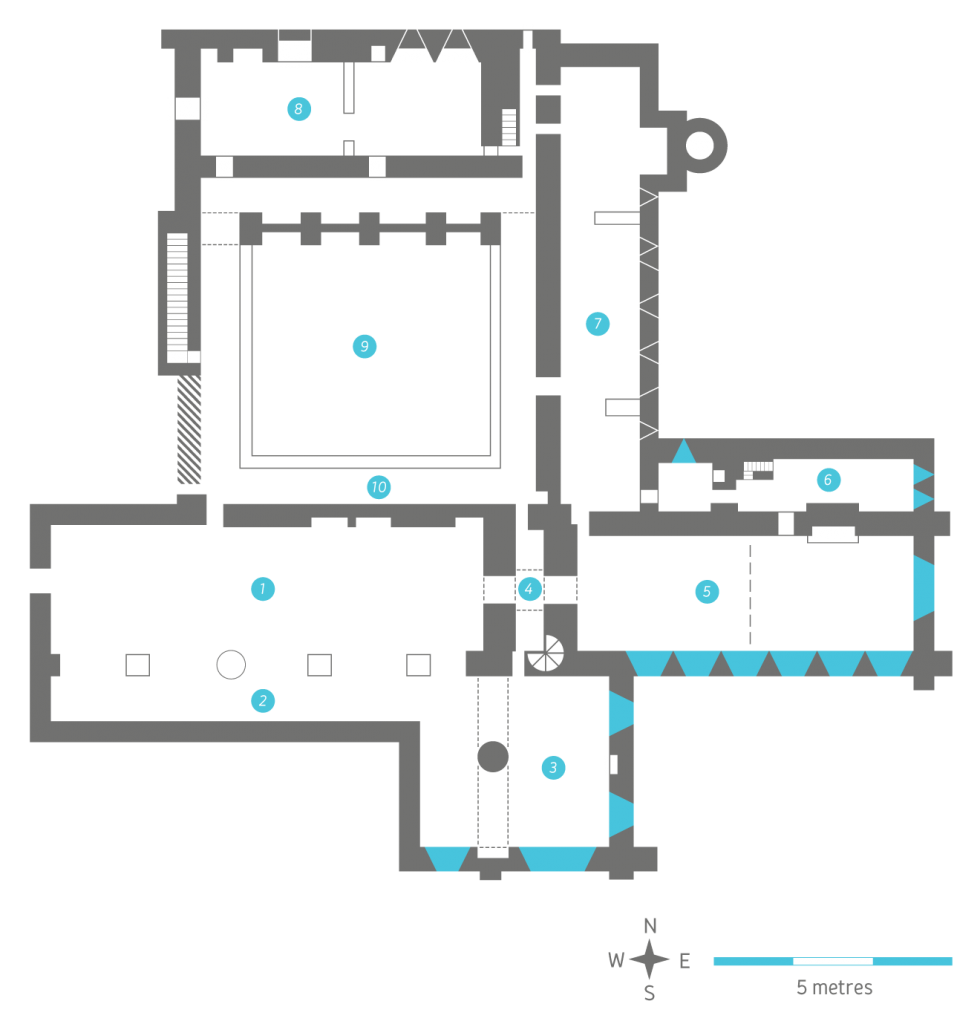

A view of the north range of the friary domestic buildings, showing the reconstructed cloister arcade. Only the east-most arch belongs to the original fifteenth-century arcade. The OPW rebuilt the other three arches from fragments, as well as the vault over the walk. The north range is an example of integrated cloister, whereby the upper floor covered the ground floor and the cloister walk, allowing for a larger space to be used upstairs. The upper room was a dormitory, which was accessible by a straight flight of stairs in the west range, as well as another stairway in a passage to the east of the range, which also connected the cloister to the outside of the friary, probably the entrance where guests would have been received.

A wall niche within the wall of the straight flight of stairs leading up to the north range dormitory. Although it is now gone, it is likely that there was west range, which would have stood just behind the stairs. The wall niche might have been used as a book cupboard.

A view of the northern cloister arcade, three arches of which, as well as the vaulted walk, were reconstructed by the OPW in the 1990s from original sections of the arcade recovered on site. Only the west-most arch belongs to the original arcade, which dates back to the 15th century, when the north range appear to have been rebuilt. This is an example of an integrated cloister, meaning that the upper floor of the range covered both the ground floor of the range and the cloister walk, allowing for larger spaces to be used upstairs, where a dormitory was located.

A closer look at the cloister arcade, comprised of two cusped, trefoil arches grouped under an arch.

This passage is located at the east end of the north range, connecting the cloister to the outside of the priory. This doorway would have been the main entrance to the priory for the friars and their privileged guests. From this passage could be accessed the cloister, the east range through a doorway on the right, and the north range dormitory, by the flight of stairs a few of which remain, on the left of the picture.