A view of the friary looking east, from the tree-lined path leading to the west entrance of the church, the same that the faithful would have taken to reach and enter the nave five hundred years ago.

A view of Kilcrea Castle, from the friary precinct. This fifteenth-century castle was also built by Cormac MacCarthy, who founded the friary, and it is located about 500 metres west of the friary church, their entrances nearly aligned.

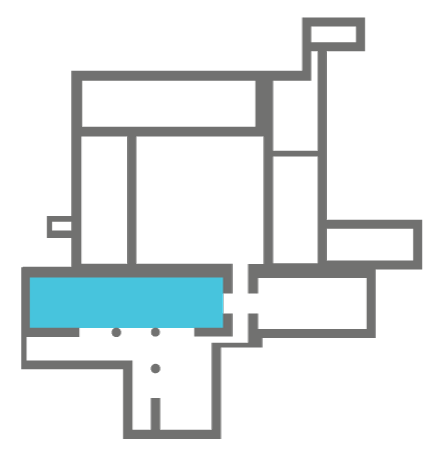

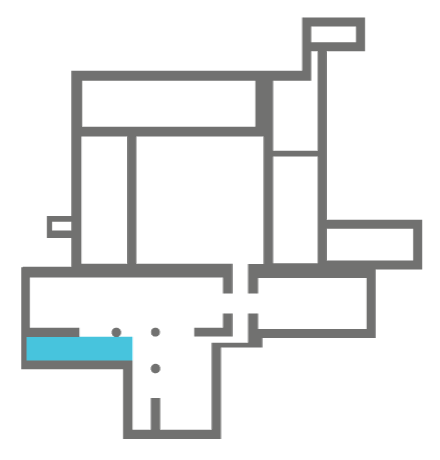

A view of the nave, looking at the crossing tower. The nave, as the entire space of the friary, is covered with modern graves. Indeed even long after the dissolution of the friary in 1542 and the complete abandonment of the buildings later on in the seventeenth century, local populations continued to hold burial rights there, and still do to this day.

Another view at the burial-filled nave, looking west, with the arcade separating the nave from the side-aisle visible to the left of the picture.

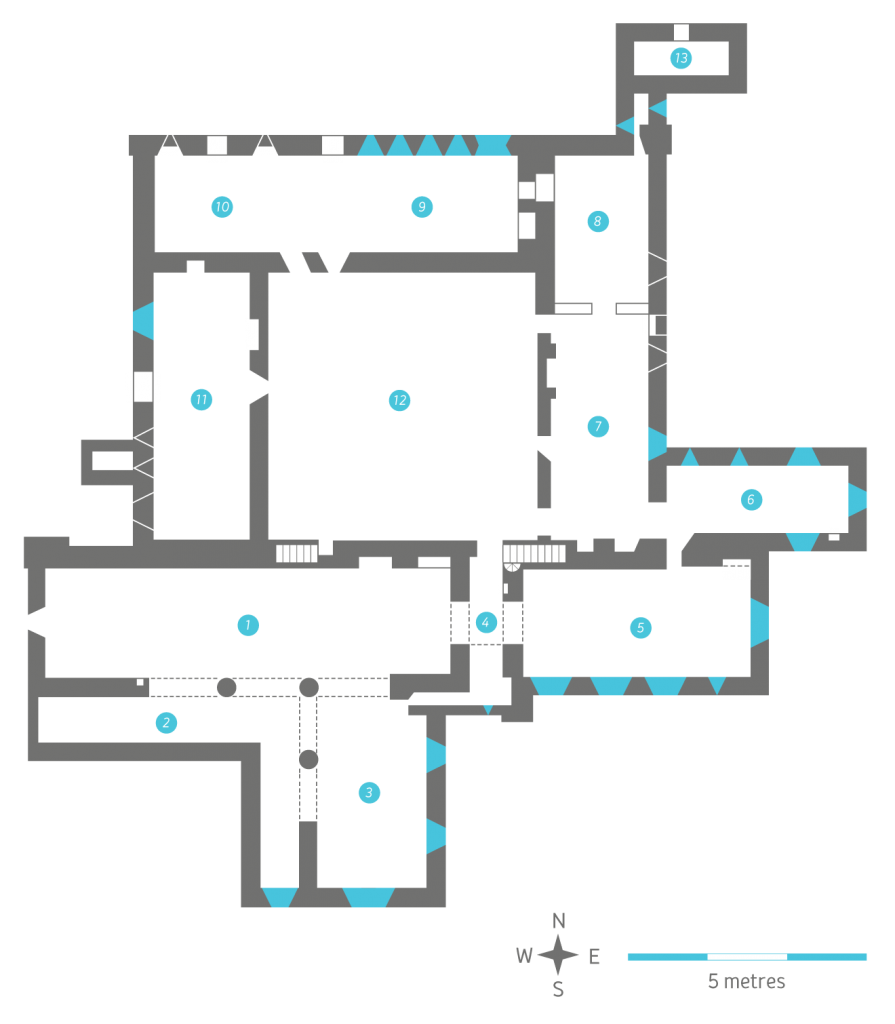

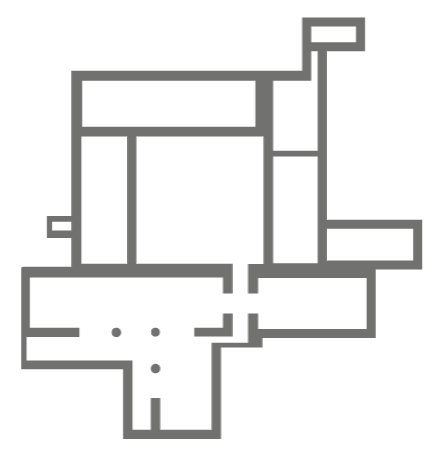

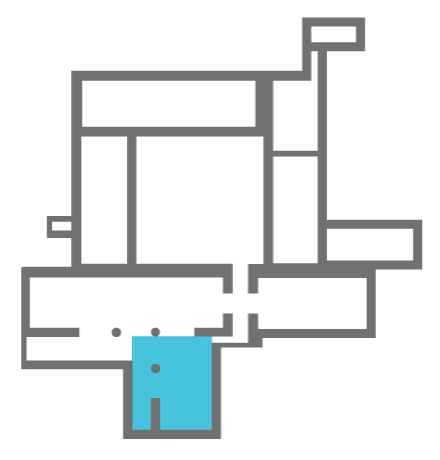

The nave was a rather long and large space, considering the rural location of the friary, away from any centres of population. It is likely that dispersed population from the surrounding area attended the church, and research has shown that the land around the friary might have been more populated than it is now, with perhaps the presence of a small village associated with the MacCarthy castle, located 500 meters west of the friary.

Two tomb niches in the north wall of the nave, close to its east end. These tomb niches quickly became a feature of mendicant friaries from the middle of the 13th century onwards, and were probably reserved to benefactors who had helped fund the construction of the church.

A view of the side-aisle and of the south chapel/transept. The three pointed arches supported by cylindrical piers are typical of the type of arcade erected in Irish churches – mendicant or otherwise – in the fifteenth-century.

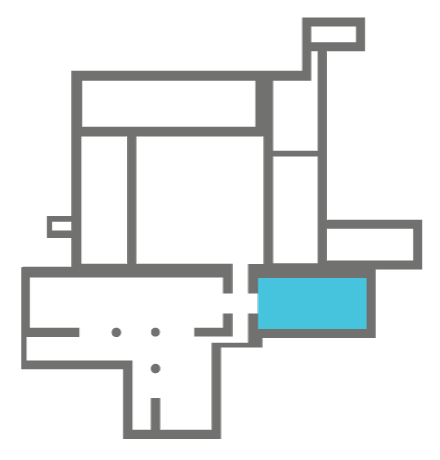

A view of the chapel, or transept, south of the nave. In fifteenth-century Franciscan friaries – and many other mendicant churches – chapels such as these were integrated to the plan of new friaries; they had begun to be added to older foundations from the late thirteenth-century onwards. Their purpose was liturgical, creating space dedicated to the cult of Mary and other saints, but also funerary. It also created space for benefactors to be buried and for the friars to pray for their soul at chantry chapels and secondary altars.

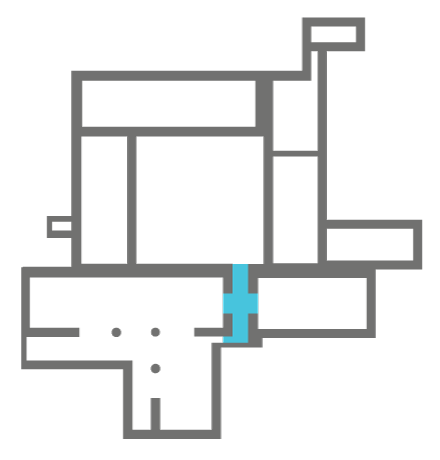

The crossing tower, which was an integral part of the original design of the church, has a slim and tapered framer, typical of Franciscan towers.

Unlike many other towers however, its two crossing arches are low and rounded, giving a more austere overall feel to the church, even in comparison to other fifteenth-century observant foundation such as Quin, with its very tall and narrow pointed tower arches.

A view of the east window in the choir. Although the tracery is gone, the small sections that remain suggest it might have been a four-light window with switch-line tracery, perhaps a similar model to Claregalway friary’s east window.

A view into the choir of the friary.

A pointed tomb niche placed at the very eastern end of the choir. It is considered the most privileged position where a benefactor could be buried, and it is usually reserved to the founder or main benefactor of the friary. In this case, it is known as Cormac MacCarthy’s place of burial, now commemorated by a modern plaque.

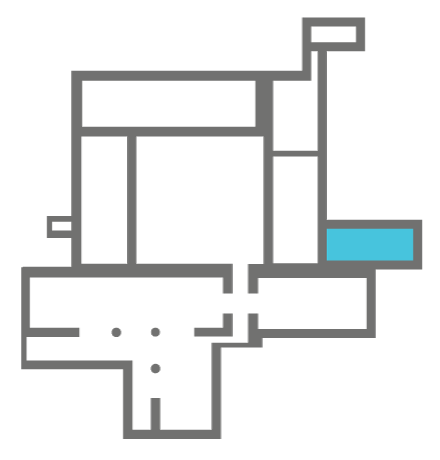

A view of the exterior elevation of the sacristy. The upper floor probably housed the friary’s scriptorium, where the friars would read and copy manuscripts. This explains the great number of windows in that floor, and probably also the fact that the building was made to extend further than the church to the east, to allow for more light to come in the room.

A view into the choir and the sacristy, which was an addition to the original plan of the friary, although it was likely build within a few years of the foundation. The upper floor of the sacristy was probably a scriptorium, where the friars would copy manuscripts, hence the many windows placed at that level. This might be where the surviving manuscript produced in Kilcrea friar in the late fifteenth-century was copied.

A view into the east range of the domestic buildings. The original interior of the friary’s domestic buildings were disturbed greatly during its post-dissolution life, as it was occupied by English soldiers, abandoned and repaired in the seventeenth century, and used again as a garrison. The lower floor was probably divided into two rooms, including the chapter room, and upstairs was the dormitory, from where the friars could accessed the lavatory, through a door at the north end of the building, seen here to the right of the upper floor’s window.

A view into the east range of the domestic buildings. The original interior of the friary’s domestic buildings were disturbed greatly during its post-dissolution life, as it was occupied by English soldiers, abandoned and repaired in the seventeenth century, and used again as a garrison. The lower floor was probably divided into two rooms, including the chapter room, and upstairs was the dormitory, from where the friars could accessed the lavatory, through a door at the north end of the building, seen here to the right of the upper floor’s window.

A view of the refectory, where the friars would have taken their meal, located in the north range of the domestic buildings. It occupied the east end of the building, where the five rounded-arch window niches are on the right half of the picture. The kitchen was placed at the other end of the building, while between the two rooms was the main entrance to the friary for the friars and for their visitors, and a short corridor from where the refectory, the kitchen and the cloister were accessible. Upstairs was another dormitory.

This window in the north range of the domestic buildings was also the site of the reader’s desk, who would have read passages from the scriptures while the rest of the community took their meal in silence.

His seat would have been placed in the alcove to the left, a desk fixed in front of him.

The cupboard-like niche facing the reader might have been used to keep the texts he read from.

A view of the west range of the domestic buildings, looking towards the church. The doorway on the upper floor to the left of the fireplace gave the friars sleeping in the range dormitory access to a staircase leading down to the cloister walk, and from there to the church. The lower floor of this range might have been used as cellars used to store food stuff.

A view of the cloister square. The cloister arcade is all but gone, and the space is entirely covered with modern graves.

A view of the lavatory building. It was a rather imposing structure, added to the east range of the domestic buildings after the friary was completed. The friars would have accessed it through a doorway in the upper floor of the east range, walking through a short corridor. It is comparable in position, size and design to the structure found in Quin friary.