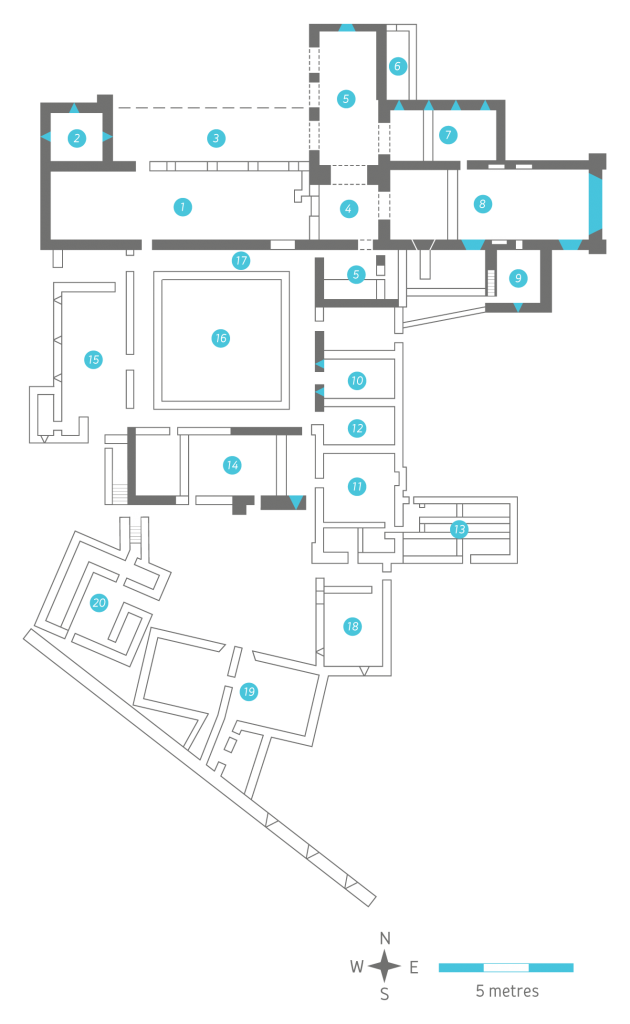

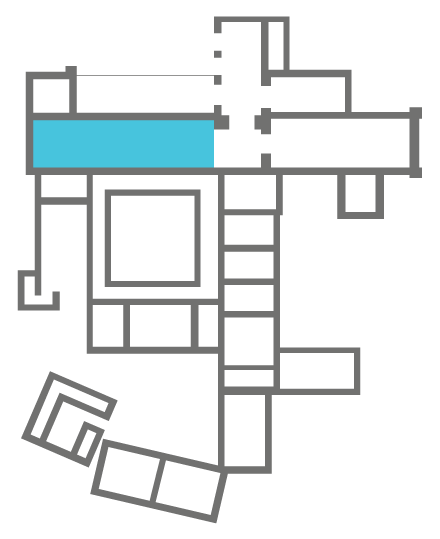

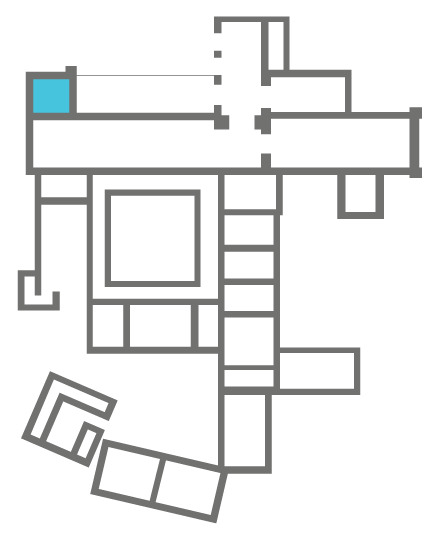

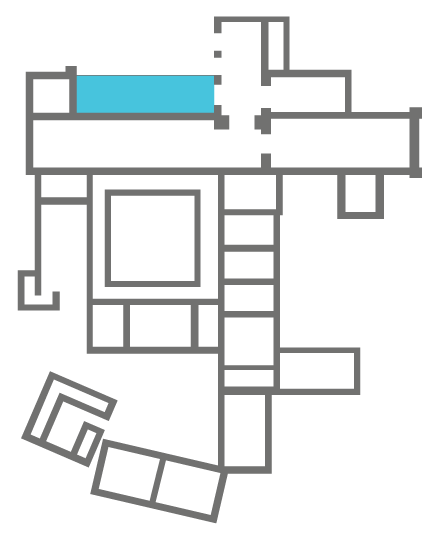

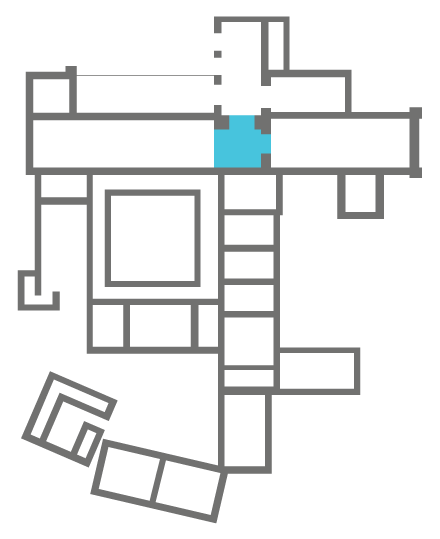

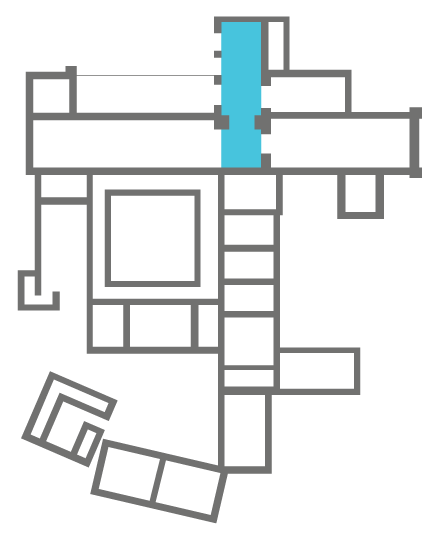

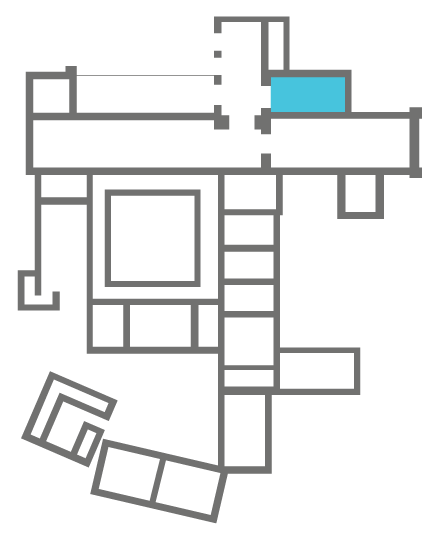

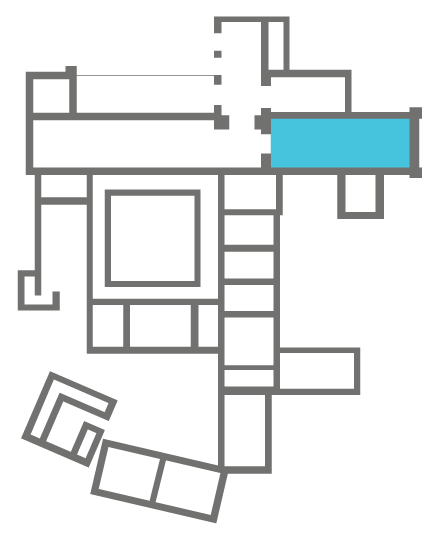

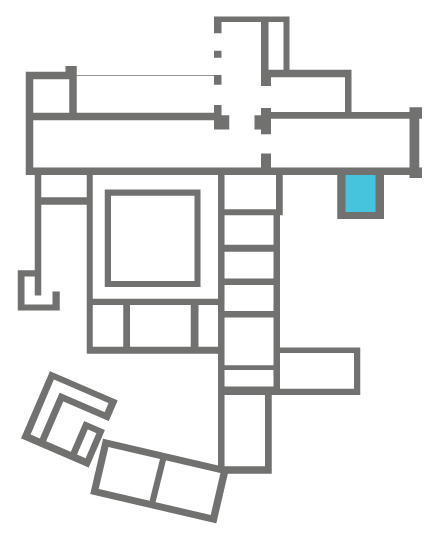

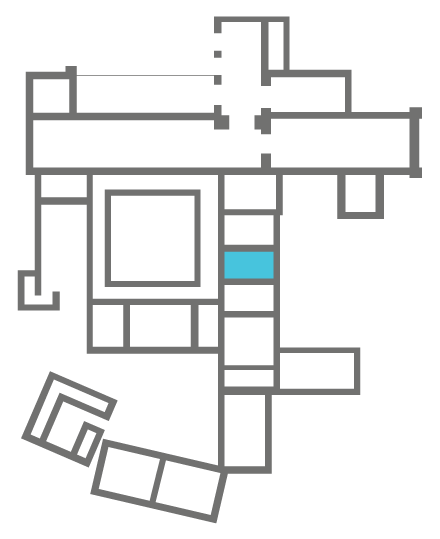

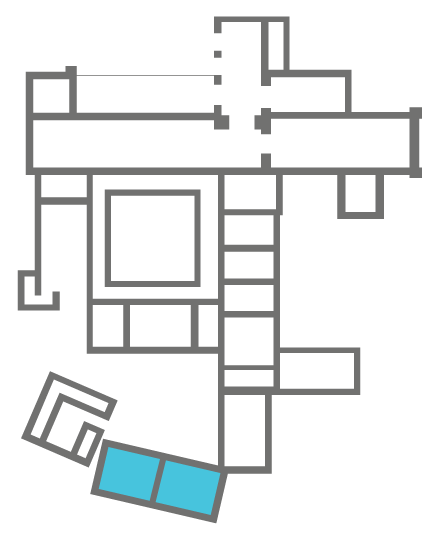

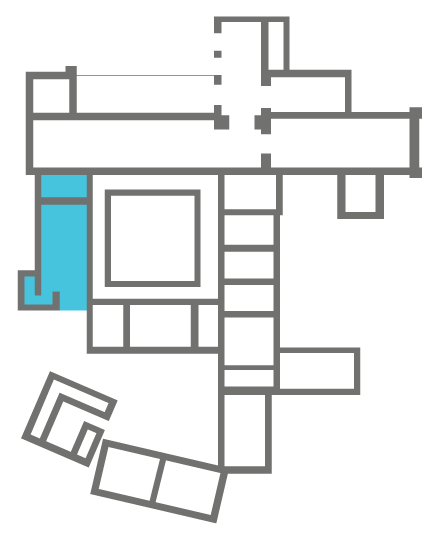

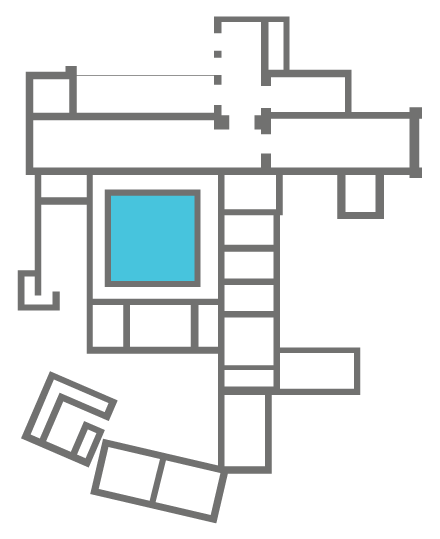

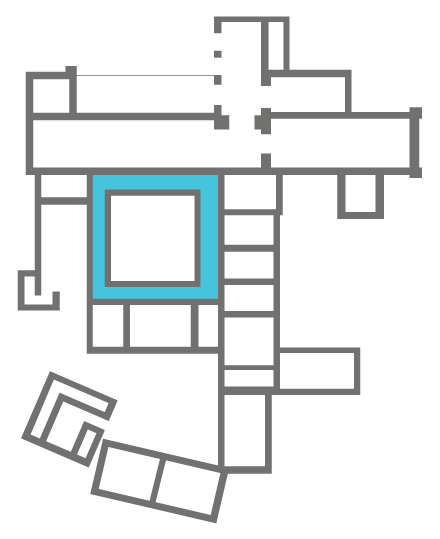

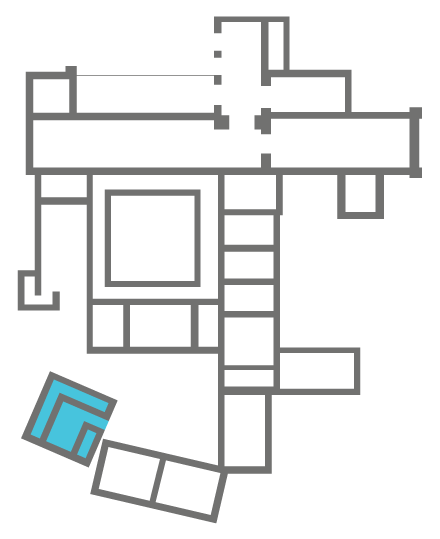

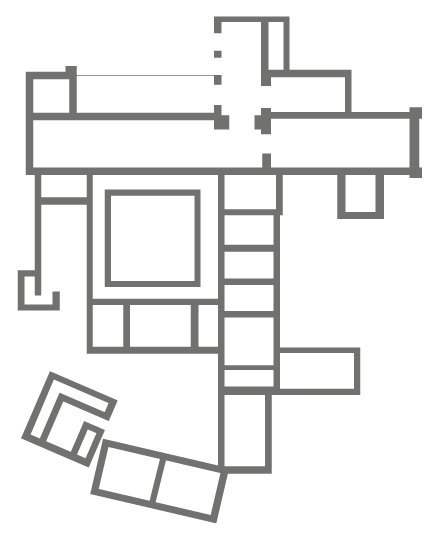

In the fifteenth century, the need for greater security in the face of war led to the construction of an incastellated enclosure, called the prior’s vill. Seen here is the south wall of the enclosure, with the southwest and south towers, which were tower-houses; indeed tenants lived within the vill, and the tower houses were leased out along with a plot of land.

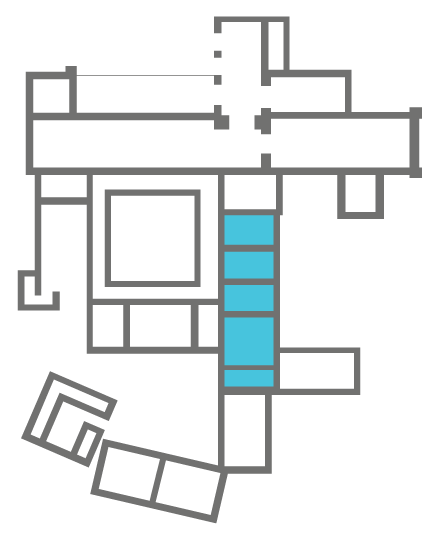

Seen here from the south, the prior’s vill is the only example of a late medieval incastellated enclosure in a monastic context in Ireland. Its primary function was defence, and each tower had their own protective system of murder-hole, loops, machicolation, cap-house and wall-walks.

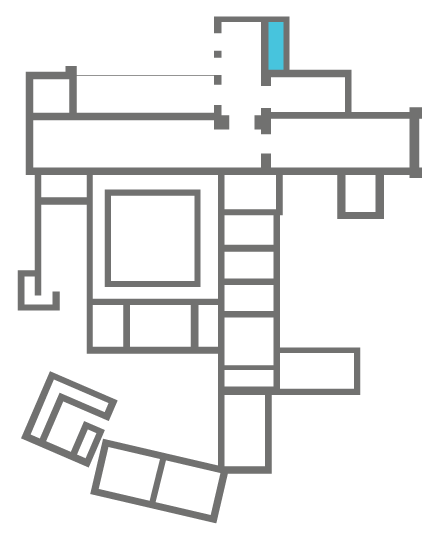

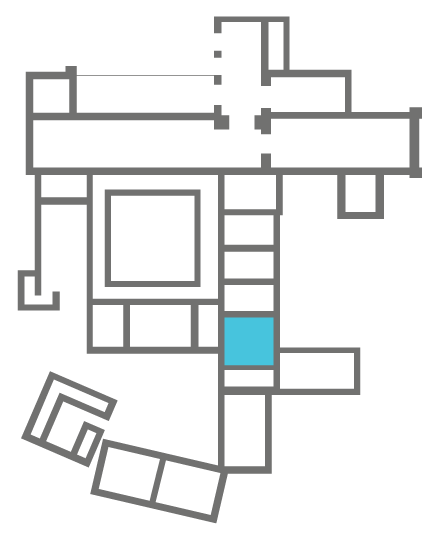

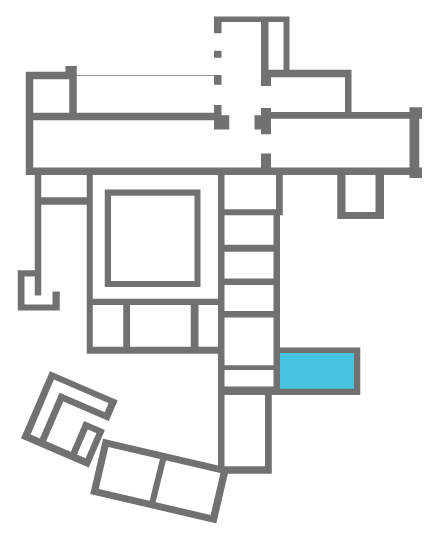

A view of the eastern gateway of the enclosure. The construction of the enclosure meant that part of the road leading to Kells town was now within the monastic site, and the gateways in the west and east walls were aligned on the roadway.