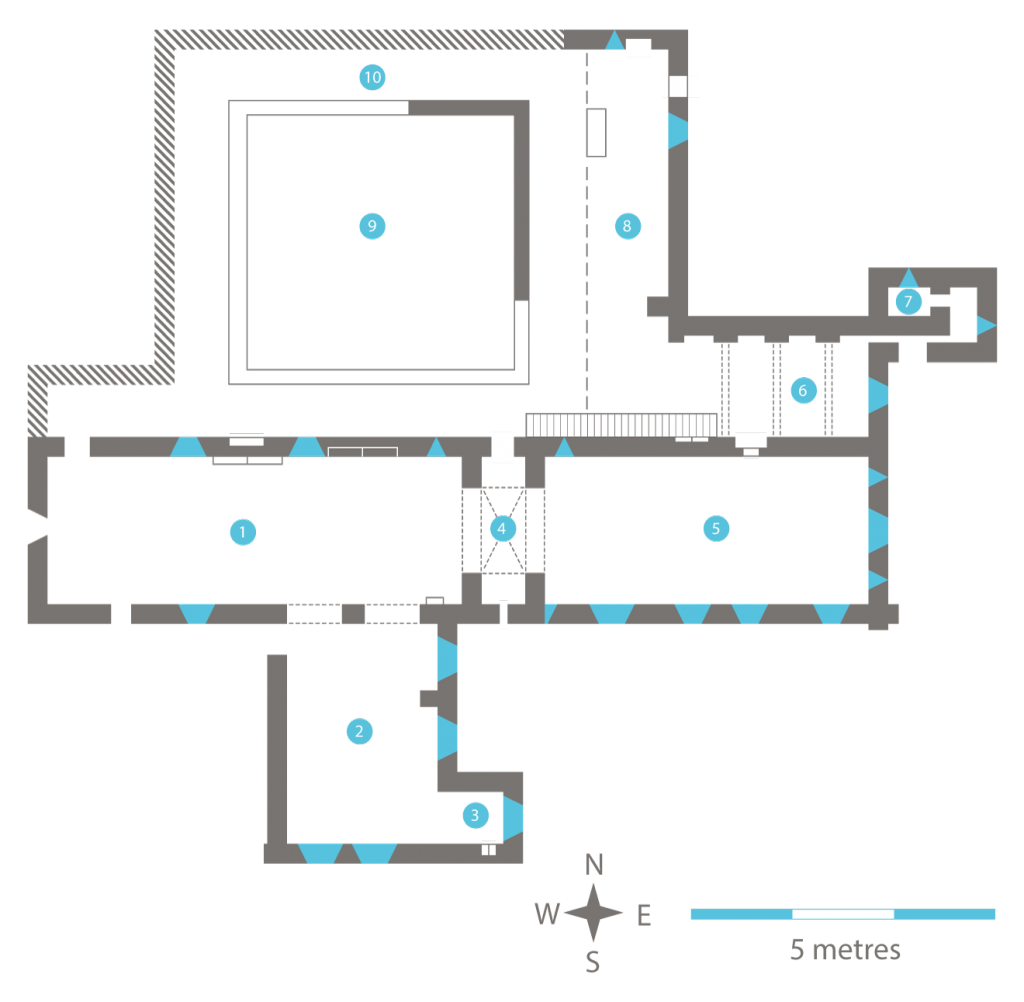

The transept is the space which intersects the nave and chancel, giving the church its characteristic cruciform appearance. These rectangular extensions to the north and south of the church provided space for additional altars dedicated to various saints and serving as mortuary, burial or chantry chapels for the community’s benefactors. In a mendicant context, only one transept arm is found, in most cases abutting the nave, or the nave and the tower between the chancel and the nave, known as a ‘one armed transept.’

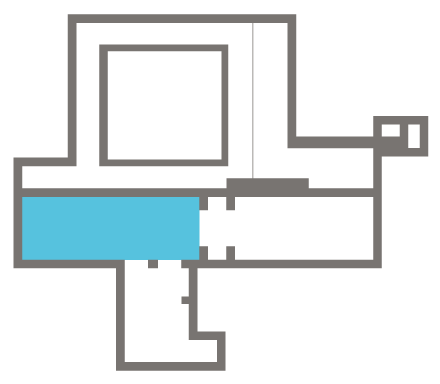

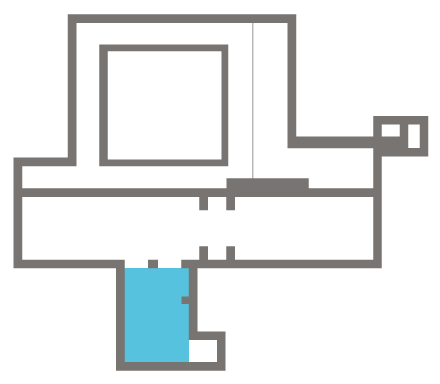

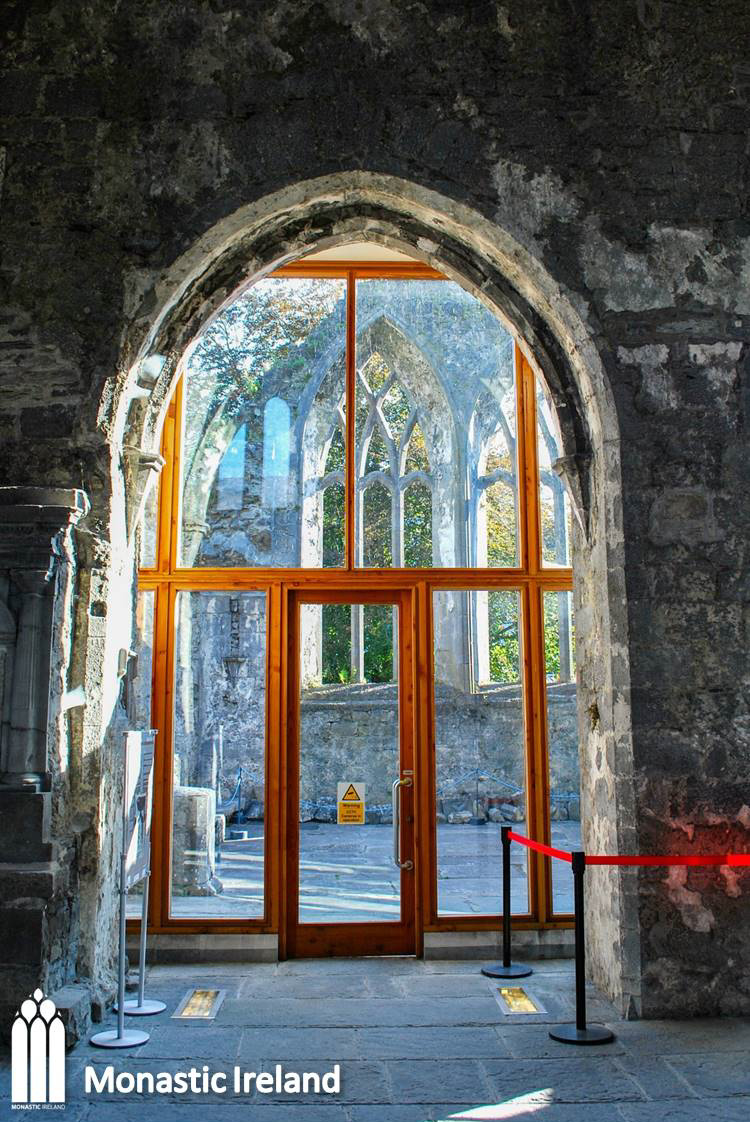

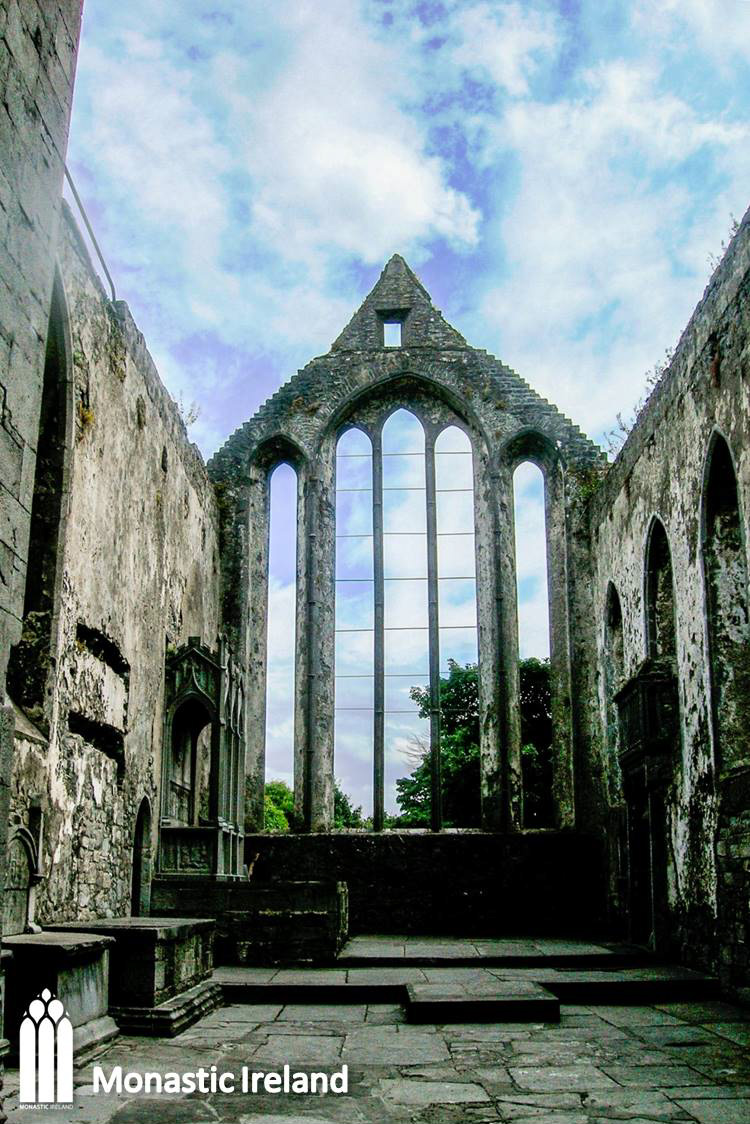

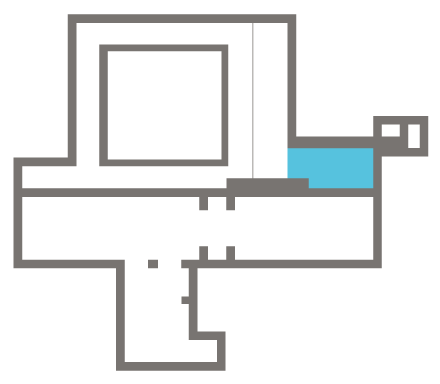

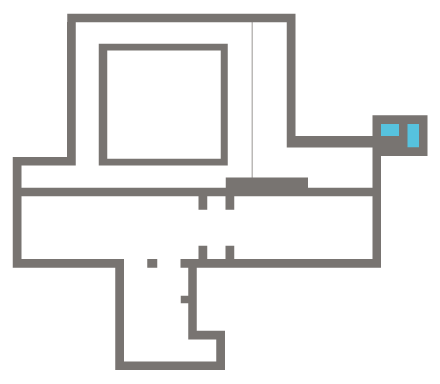

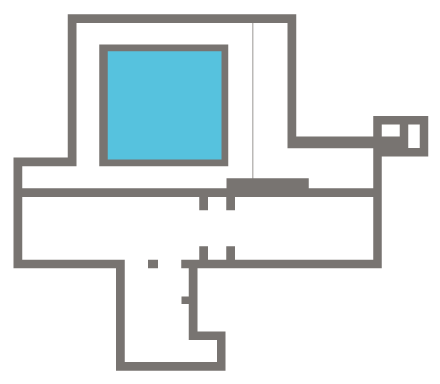

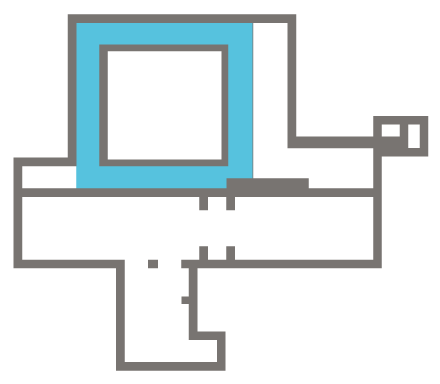

A view of the south transept through one of the two arches of the arcade that separated it from the nave. The image of the Man of Sorrows described below is inserted on the inside of the arch to the east. The south transept was added to the church in the fifteenth century. These large funerary and devotional spaces were added to many mendicant churches from the fourteenth century onwards, and in Ennis its construction was probably funded by members of the powerful O’Briens, who were the main benefactors of the friars.

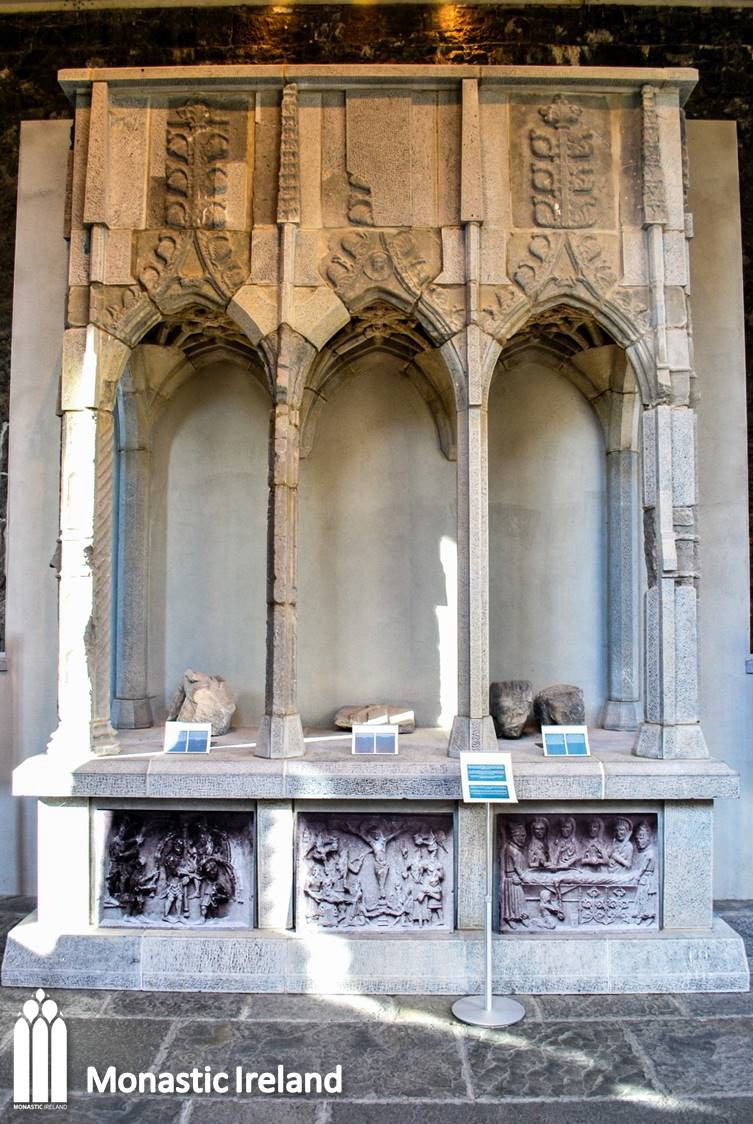

The image of St Francis is paired with an image of the Man of Sorrows on the other side of the nave, but this time inserted on the east face of the arch leading into the south transept. Again, its position indicates that it was aimed to be viewed by the laity, for devotional purposes. It is a rare Irish example of a popular iconographic representation of Christ with the wounds of his Passion prominently displayed on his hands and side. Here he appears as a skeletal figure, dead yet alive, surrounded by the Instruments of the Passion. As well as its devotional function, this image would have also served as a reminder to the faithful of the sacred events of the Passion and the Resurrection.

A closer look at the carved image of the Man of Sorrow, representing Christ as a skeletal figure emerging from his tomb. This image as well as the portrait of Francis in the nave, the five panels of the Passion of the MacMahon Tomb and the fragmentary Pieta now exhibited in the restored nave all appear to have been produced by the same workshop, or perhaps even by the same artist, probably between 1460 and 1470.

The transept has not one but two large windows in its south gable, which are both triple lights with switch-line tracery, similar in style to the window in the west gable of the nave. They would have made for a particularly bright space, and it is likely that secondary altars serving private chapels would have been accommodated underneath each of them.

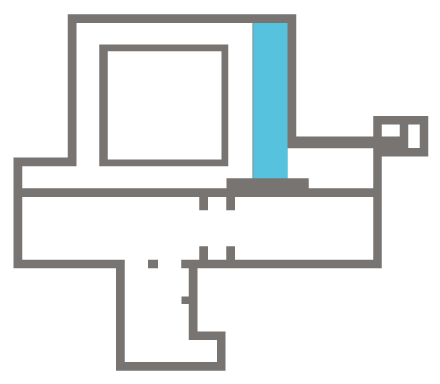

A view of the south transept from the gardens outside of the church, showing how it abuts the nave.

Back to top

Back to top