A view of the remains from the church, taken from the cemetery outside. The church is located about 37 meters from the main road, in the southeast corner of what is now the burial ground of St Mary’s Catholic Church.

This is the western façade of the church, through which the congregation entered the church. The grave slabs in the foreground are post-medieval, and you can see from the position of the church doorway how continuous burial activity around the church has raised the ground high above the original medieval level.

A view of the interior of the nave, looking towards the chancel. Here too, burials have continued to take place following the Dissolution and to this day. Dividing the nave from the chancel used to be a tall belfry tower, which collapsed in the 19th century.

A close look at a thirteenth-century tomb niche in the north wall of the nave, one of three of similar design found in the church, with a cinquefoil moulded arch and jambs with sculpted capitals and bases.

One of the two other thirteenth-century tomb is located in the south wall of the nave, next to the pointed arch leading into the south transept.

A close look at the altar-tomb located at the east end of the nave, to the right of the collapsed crossing tower. An eighteenth-century drawing of the friary completed before the tower collapsed shows that a similar altar-tomb also stood on the other side of the tower central archway. These altars would have been used for the celebration of private masses.

This piscina with a pointed arch and moulded bases is associated with the altar tomb placed at the east end of the nave, and is located on the south wall beside it.

A view of the interior of the nave looking toward the west gable. The two windows above the west doorway were originally two simple pointed lancet. Ogee-headed double-lights were inserted at some point later on, probably in the fifteenth century, when such upgrades were common in friaries.

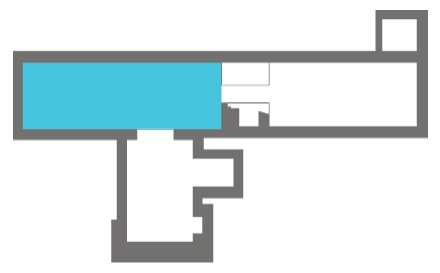

A view of the interior of the south transept, looking through the pointed arch leading into it from the nave. Transepts were in fact built to house chantry or memorial chapels associated with the patronage of friaries, where benefactors were buried and paid to have prayers and private masses to be said for their souls by the friars.

This is the tomb niche in the east wall of the south transept where one of the three cinquefoil-headed tomb arch used to be located before it was moved to be placed under the east window of a later built chapel projecting off the east wall of the transept.

A view of the exterior of the south transept. At a later time, the south gable of the transept was encased in an outer wall which extended around the east and west wall and blocked the south most window in the latter, seen here. It was built to reinforce the original foundations of the structure, weakened by the slope of the ground.

A view of the chapel projecting off the east wall of the transept, through the pointed arch leading into it. It was likely a chantry or funerary chapel paid by a patron, used as a burial vault for him and his family and which would have been fitted with an altar for private masses to be said for their souls by the friars.

A closer look at the east gable of the chapel projecting off the transept to the east. At some point in time, probably after the Dissolution of the friary, the cinquefoil arch of the thirteenth-century wall tomb originally placed in the east wall of the transept was taken and reused for a new burial arranged in the east gable of the chapel.

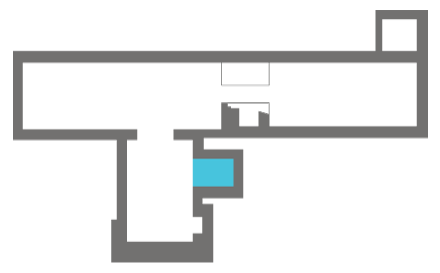

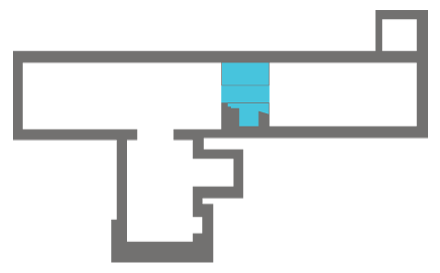

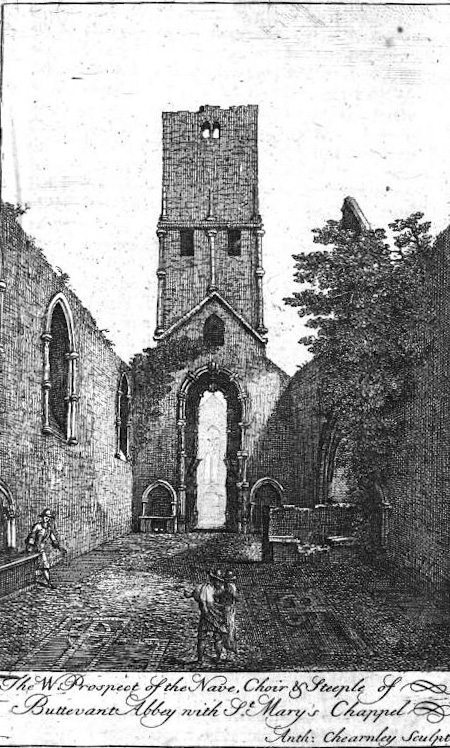

A view of the remains of the belfry tower which used to stand between the nave and the chancel. The tower was quite an early addition, probably in the late thirteenth century, making it one of the earliest example of such structures in a mendicant context. Such towers were to become widespread in the fourteenth and fifteenth century. An eighteenth-century engraving of the church before the tower collapsed shows it as a tall and slender structure, typical of the type seen in most surviving Franciscan friaries. (Image courtesy of Andreas F. Borchert)

This engraving published in Charles Smith’s The Ancient and Present State of the County and City Cork in 1750 shows the ruins of the church before the tower collapsed in 1819. It depicts a tall and elegant tower with the two altar tombs extant on each side of the tower arch, with its elaborate mouldings punctuated by shaft bands, which are repeated along the corners and façade of the tower itself, picking up on those decorating the jambs of the nave windows.

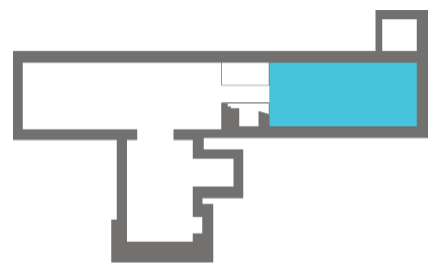

This is a view of the interior of the chancel, taken from the nave. The photo was taken when conservation work was taking place in the church and the chancel was not accessible to the public. The work has now been completed and visitors can enjoy the building in full. The east window was originally comprised of three tall, thirteenth-century graded lancet windows. Later on three shorter windows were inserted, the central one with late fifteenth-century tracery.

The west half of the north wall of the chancel has been reconstructed using a number of fragments of the friary’s cloister arcade recovered during conservation work. It comprises elements typical of mendicant cloisters built in the 15th century in Ireland, such as the moulded bases, capitals and twisted shafts of dumb-bell piers, a standing example of which can be found in Sligo Dominican priory for example. (Image courtesy of Andreas F. Borchert)

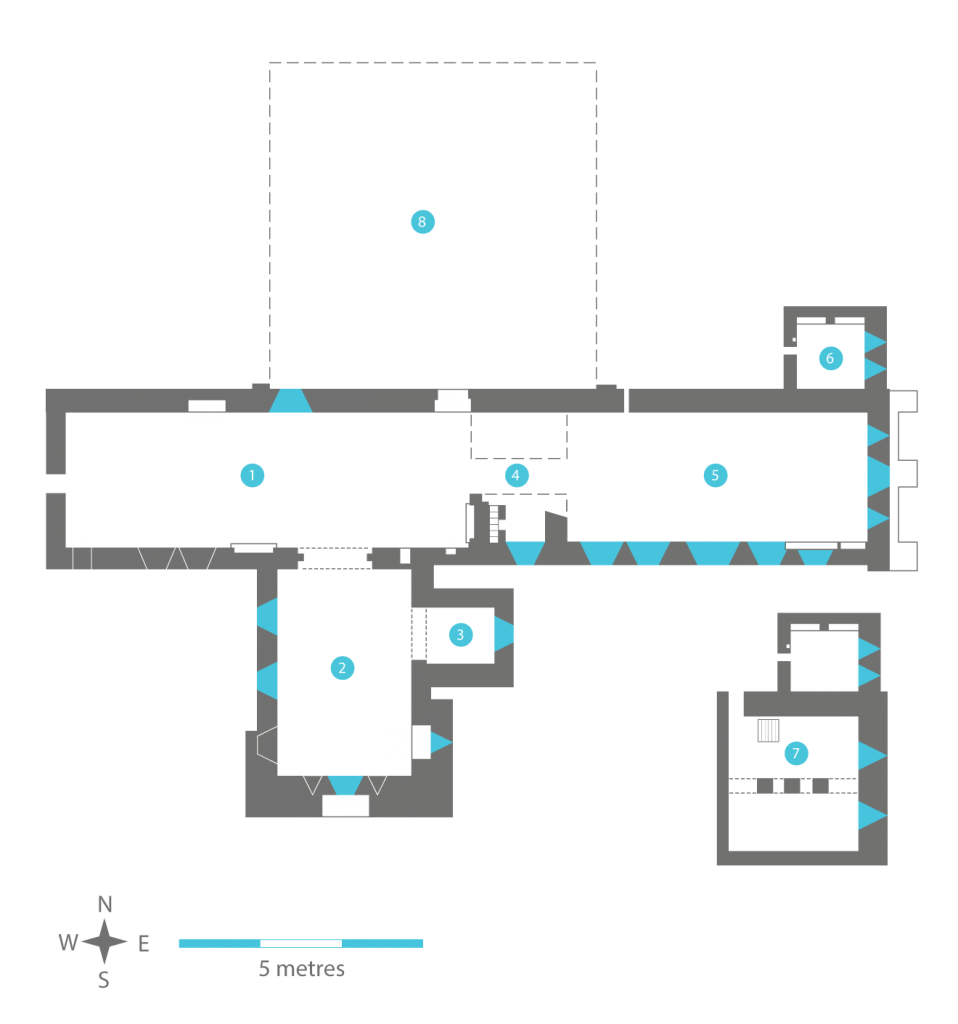

Nothing remains above ground of the domestic buildings that once extended to the north of the church, but traces of a room with an undercroft can be found directly to the north of the chancel, in front of which was a sort of antechamber where stairs lead down to the crypt. It was probably the sacristy, although it has been suggested that it could have been the Chapter House.

Very unusually, the chancel was built over a two-storey crypt. Medieval crypts are very rare in Ireland, and it is the only example in a mendicant context. Both levels are barrel-vaulted, supported by central pillars, the one in the upper chamber decorated with stiff leaf ornament. Prof. Tadhg O’Keeffe has suggested that the crypt might in fact have started as part of a completely different building, perhaps a castle predating the arrival of the Anglo-Normans to Buttevant, later taken over by the Barrys and offered to the Franciscans to build their friary over.

(Image courtesy of Kieran Hynes)

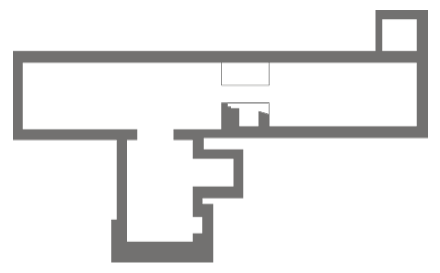

A view of the north wall of the nave, to which abutted the cloister and the west range of the domestic buildings of the friary. The string course which begins underneath the double lancet window marks the extent of the cloister walk that ran around the cloister garth, and it supported the lean-to roof that covered it. Beyond the string course and window to the west stood the west range.

A view of the north wall of the church, with St Mary’s Catholic church cemetery in the foreground, where the cloister and the domestic ranges of the friary used to stand.