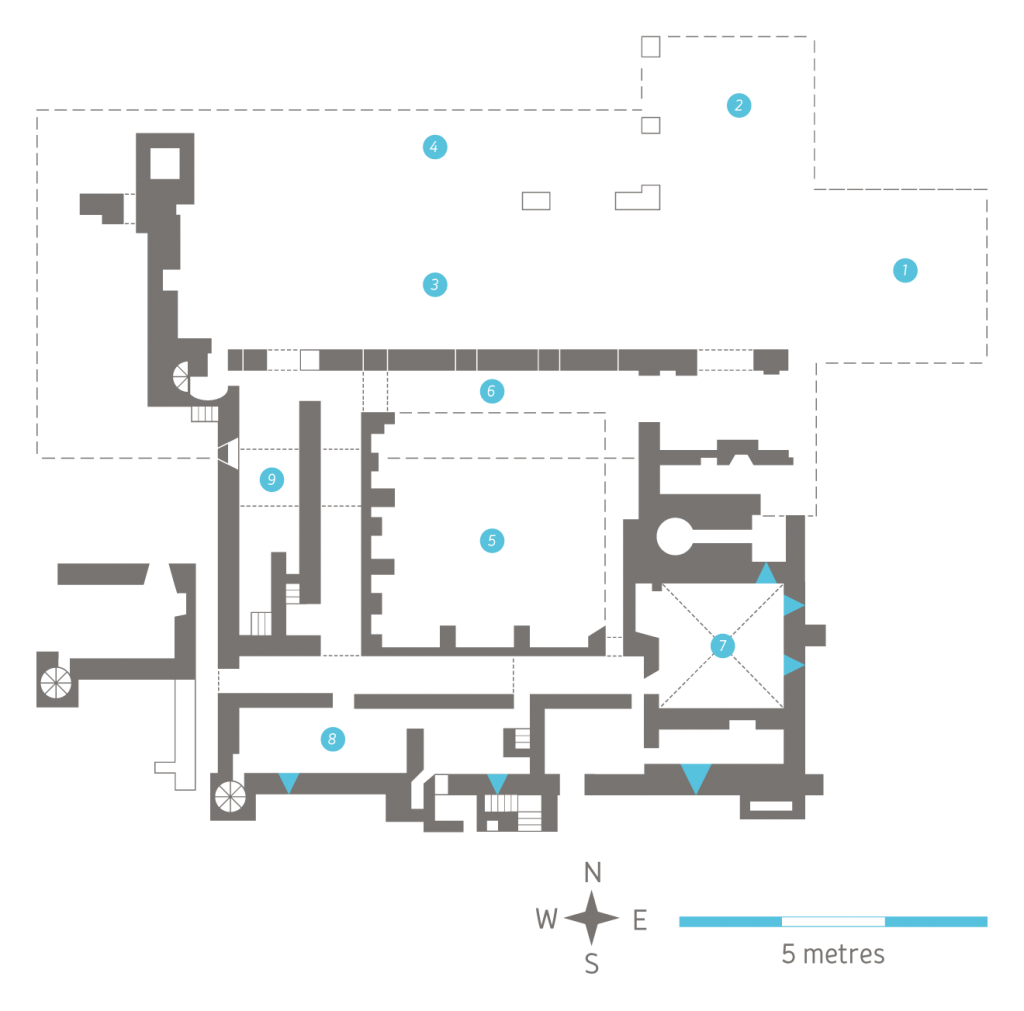

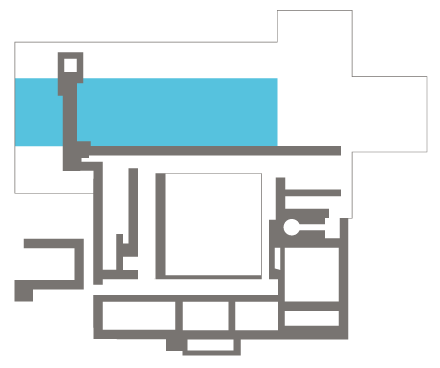

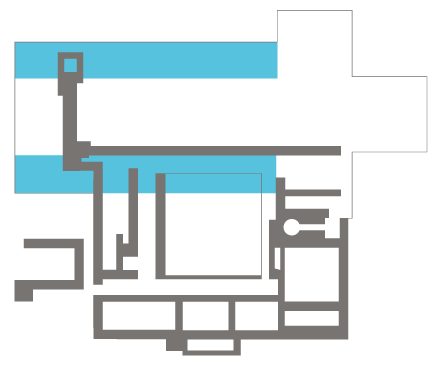

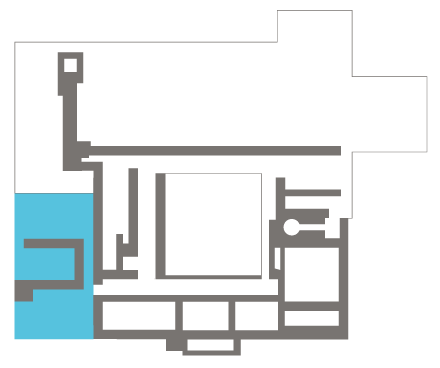

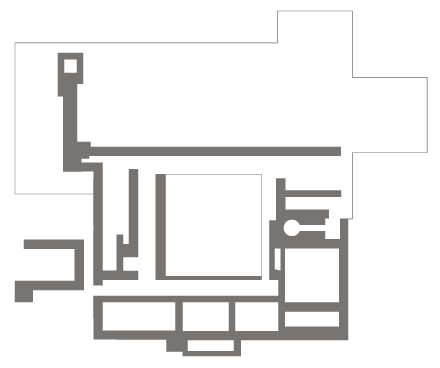

Nothing remains above ground of the chancel or presbytery of the thirteenth-century abbey church, and very little remains of the rest of the building, though there is enough to figure that its plan followed the ‘Bernardine plan’ developed by Bernard de Clairvaux in the mother house of the order in Citeaux and that he encouraged in all early foundations: a cruciform plan with an aisled nave and two square chapels in each transept arm, and the cloister and domestic buildings to the south.

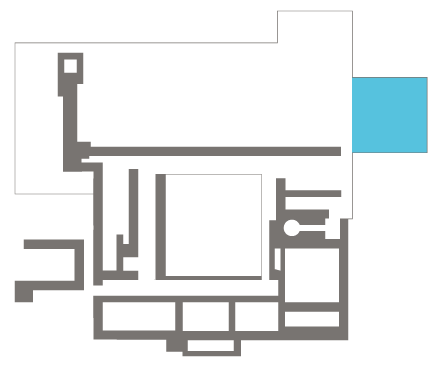

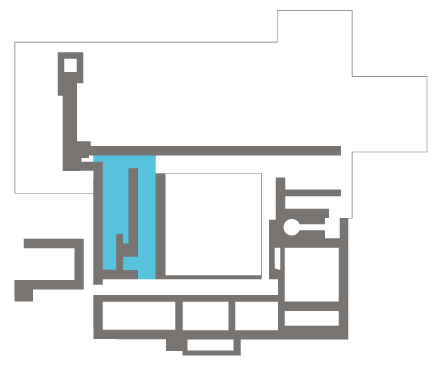

A view of the transept looking at the only crossing arch that remains, though it dates to the fifteenth-century remodelling of the church, and is narrower than the original archway.

A view of the fifteenth-century west gable of the nave, reinforced by a square protective tower to the north.

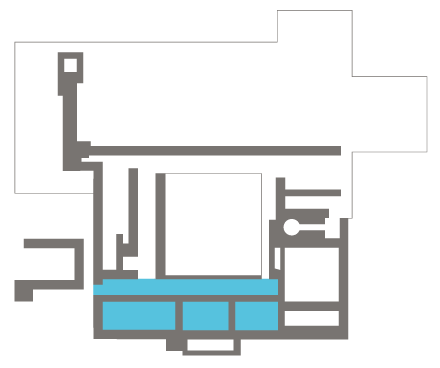

The nave was shortened in the fifteenth century, with the construction of a new west gable and a protective square tower to the north. The south aisle was blocked at that time too, and incorporated into the design of the new, smaller cloister.

Very little remains of the two aisles of the thirteenth-century church. Most of the fabric of the south arcade remains but it was much altered during the fifteenth-century remodelling of the church, when the aisle was abandoned and its five arches blocked, and in the sixteenth century when the abbey was transformed into a Tudor residence. The north aisle on the other hand, is almost completely gone.

A view of the site of the south aisle of the church, which was abandoned in the fifteenth-century. The outline of the blocked arches of the aisle can still be seen. At that time the aisle was integrated in the design of the new, smaller cloister, and two ogee-headed three-light windows were inserted, one of which survives. To the extreme right of the picture is the remains of the original thirteenth-century arch which connected the south aisle to the transept.

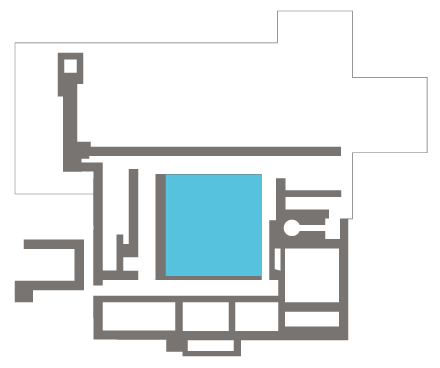

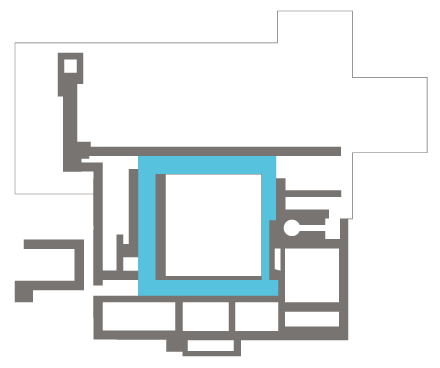

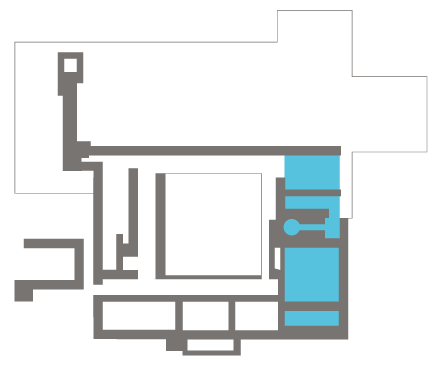

The small, intimate cloister at Bective was constructed in the fifteenth century, when the abbey was reduced in size. The original cloister extended over the site of the fifteenth-century south and west range. The south walk of the original cloister was incorporated into the new south range, while the church south aisle became the new north walk. On the two sides pictured here, to the west and south, the new cloister was integrated, with vaulted walks and upper floors extending over them. This allowed for a smaller, more compact overall design but with spacious upper floors to accommodate the dormitories.

In contrast to the west walk, the north walk of the fifteenth-century cloister was originally covered with a lean-to roof, as was the east walk, allowing the church behind it to be lit above by a large three light window. It was probably demolished in the sixteenth century.

This window, a trefoil ogee-headed triple-light, was inserted into the south wall of the church during late fifteenth-century remodelling of the abbey.

The vaulted walk of the south side of the cloister originally supported the dormitories located above. The design of the cloister arcade is quite typical of the fifteenth century, with arcades of three cinquefoil pointed arches with fine mouldings grouped under a flat arch, and separated by large, rectangular buttressed piers. Each arch rests on a variation of the widespread dumb-bell piers made up of two clusters of three half-colonettes.

The effigy of a kneeling abbot is carved on the east side of a pier in the south walk of the cloister. He is holding a crozier and praying, under a canopy and a coat of arms with two fleur-de-lis. This might represent Bernard de Clairvaux, as this is a depiction of the saint commonly found on various supports across medieval Europe.

The Chapter House, which remained in used from the thirteenth century until the Dissolution of the abbey, is unfortunately closed to the public. Its entrance from the cloister walk can be seen on this picture, at the east end of the south walk. It is a large groin-vaulted room, the vault springing from a central octagonal pillar. In the sixteenth-century Tudor transformation of the abbey it was turned into the kitchen, and a large fireplace was inserted in its west wall.

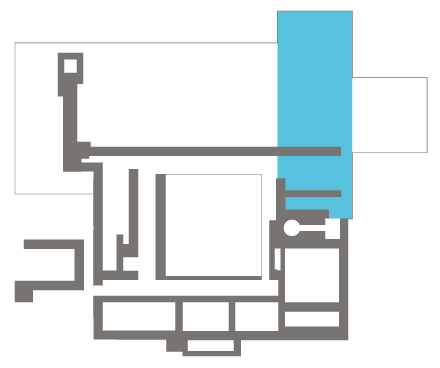

The tall chimney and relatively large gable window reflect the conversion of the east range into a comfortable Tudor dwelling by vice-Treasurer Thomas Agard shortly after the Dissolution.

The east range was the only thirteenth-century domestic range which survived the fifteenth-century remodelling, although it was shortened to the south. It was connected to the south transept of the church, where the night stairs would have led the monks directly down from their dormitory into the church. It was comprised of the sacristy, a large, vaulted chapter house and a slype or passage. At the Dissolution the sacristy became a bake-house fitted with a large oven, and the chapter house a kitchen; a rather symbolic conversion of what would have been the most liturgically important rooms of the abbey beside the church, into the most profane spaces of a house.

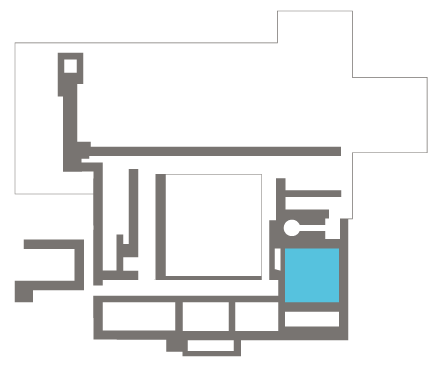

This strong defensive tower, used as an abbot’s lodging, was added in the fifteenth century. The broad staircase was added when the abbey was converted into a house in the sixteenth century, providing a grand entrance to the new Tudor residence. It led to the upper floor of the south range, originally the monks’ refectory, which was turned into the main hall of the house. The original, thirteenth-century south range extended to the south of the remains, and the fifteenth-century range was built on the site of the original cloister walk.

This passage connected the south cloister walk to the outside of the abbey, effectively to the site of the original west range. It also created a physical separation between the laybrothers’ quarter (west range) and the south range, where the abbot’s lodging and the refectory were located.

A view of the fifteenth-century west range through one of the arch of the thirteenth-century church. This arch was blocked during the remodelling of the abbey in the fifteenth century and a doorway was inserted connecting the nave to the new west range, with was also the lay brothers’ quarter.

A view of the upper floor of the west range. The west and south range of the new remodelled cloister of the abbey were of the integrated type, with the upper floor extending over the ground floor and the cloister walk, and in this picture we can see it in section, with the vaulted walk and room below the larger space of the dormitory. At the south end of the range is the fortified tower house also constructed in the fifteenth century, and which housed the abbot’s lodging.

Another view of the upper floor of the west range of the abbey. During the abbey lifetime the west range was the lay brothers’ quarter, with their dormitory in the upper floor. During the transformation of the abbey into a Tudor house, the west range became one the two main domestic wings of the secular residence.

A view of the site of the thirteenth-century west range, which was the original laybrothers’ quarter. The only standing remains is that of the cellarium, of which the upper floor continued to be used as part of the remodelled abbey in the fifteenth century. In the excavations carried out in 2009-12, a building with stone drain, hearth and pit was uncovered at the south of that range, which might have been the site of the abbot’s residence at the time.

Located in the lush Meath countryside, Bective was a relatively wealthy abbey. The nearby bridge gave the title to the 1942 book Tales from Bective Bridge from writer Mary Lavin, who lived nearby.

The fortified appearance of Bective abbey reflects its wealth during the later medieval period, the dominant south-west tower overshadowing the more modest, earlier parts of the building.

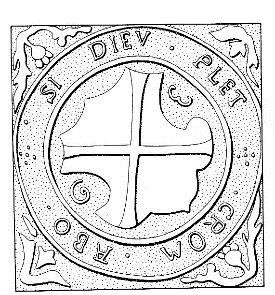

Line-impressed tiles found at Bective (NMI) bear the arms and motto of Gearoid Mór FitzGerald, earl of Kildare from 1478 to 1503. Their presence at Bective suggest that the remodelling of the church and domestic ranges may have been completed under his patronage