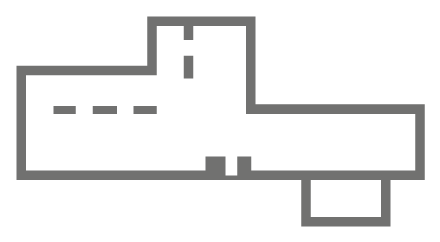

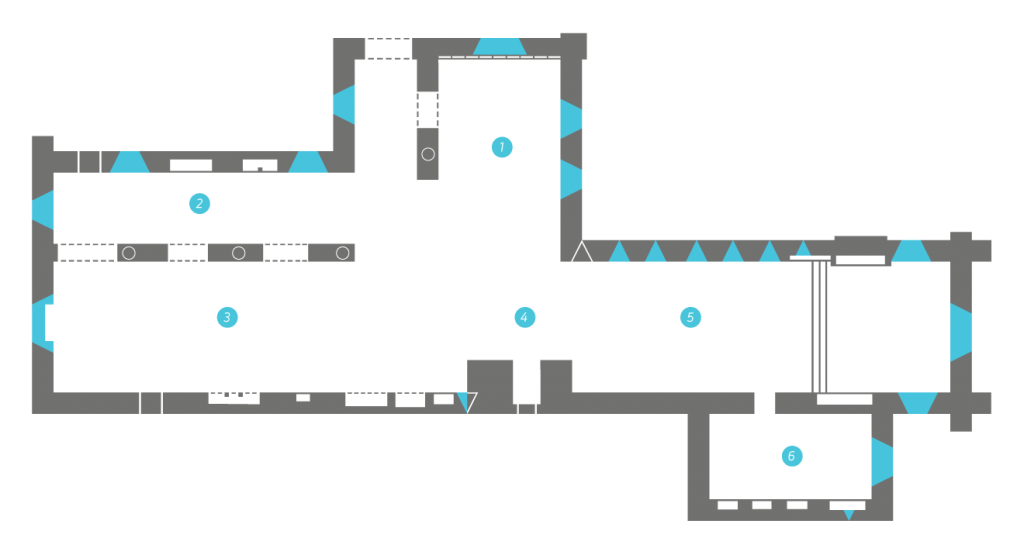

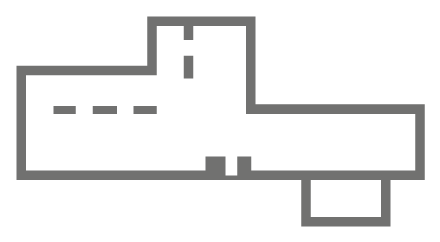

A view of the north elevation of the church. It stands within a graveyard that is not in use anymore, and the main access is through a doorway in the north transept. It is locked and the key is with a caretaker that lives nearby.

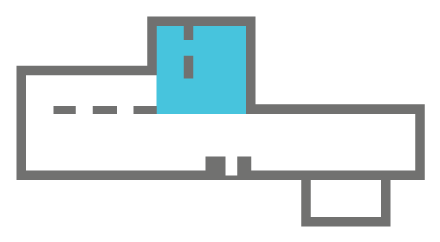

A view into the north transept – or chapel – which was built in the fourteenth century to the north of the nave and dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The tracery in the large four-light window was reconstructed from fragments. The blind arcade spanning the entire north wall below the window is composed of three sets of triple trefoil-headed arches; they are probably tomb niches associated with the benefactors mentioned in the priory medieval register, involved in the construction of the chapel, and buried within it.

A view of the north window of the transept, with its ornate tracery reconstructed from loose fragments and their analysis by OPW’s architect Harold Leask.

A view of the east wall of the north transept, showing a pair of twin-light windows with switch-line tracery. It is not certain exactly when the north transept was built, but it is definitely a later addition to the church, as it blocked half of the west-most lancet window of the chancel. We also know from the priory register that its construction was funded by Mac a Wallyd Bermingham ‘up to the bases of the windows’, and completed by William Wallace, burgess (inhabitant) of Athenry, who died in 1344.

The church is now accessed through a doorway in the north wall of the transept lateral aisle. This aisle was separated from the main space of the transept by an arcade that would have connected with that of the nave’s own lateral aisle, also an addition to the original, thirteenth-century church.

This is one of two tomb niches located in the north wall of the aisle, between the two windows. The priory register suggests that the benefactor responsible for these monuments might have been one Walter Braneoc, who created a funerary chapel in the north aisle sometime before 1423, when the priory burned down. He paid for repairs afterwards and was buried in the chapel, as were several members of his family. It is likely these two tomb niches belong to the chapel.

Though the tracery of this west-most niche is gone, the sections that remain indicate that it would have been identical to the other one.

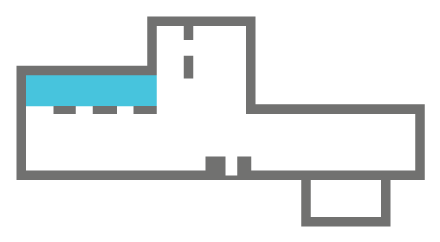

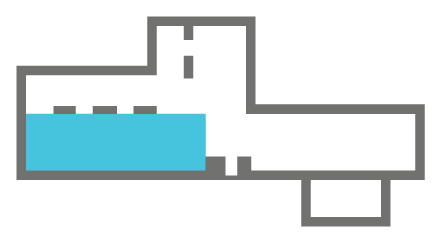

The nave’s lateral aisle was likely added to the church at the same time as the north transept. It is separated from the nave by an arcade, three of the five arches of which remain. The original arches of both the aisle and the transept were taller and rested on circular columns, but were later partially blocked up, the columns encased in the fabric.

A view of the north wall of the nave’s lateral aisle. Again the priory register help us making sense of the building, telling us that Edmund Lynch (d. 1462) repaired this wall (probably following the 1423 fire), including the glazing and the tracery of the windows, which indeed suggests a fifteenth-century date.

Looking down the nave, from the chancel. The division between nave and chancel would have been physically marked by the belfry tower built in fourteenth century, but it is likely that a screen, or perhaps a succession of two screens, marked the division of space beforehand.

A view of the south elevation of the nave, showing a number of features surviving in a more or less damaged state, and dating to various periods: two thirteenth-century tomb niches, with a double piscina to the left, which would have served a secondary altar, and a sixteenth-century round-headed statue niche to the right. The tomb niche in the middle was composed of three trefoil-headed arches very similar to those making up the blind arch in the transept north wall.

This thirteenth-century tomb niche is also placed in the south wall of the nave and is composed of moulded, rounded trefoil arches resting on thin, free-standing columns with moulded capitals. The presence of these funeral monuments is directly connected to the numerous benefactors of the priory who helped fund its construction, many of whom are mentioned in its surviving register.

An external view of the west gable of the nave, which was used as the wall of a handball alley in the nineteenth century, as it became quite a popular sport at the time. Most of the wall was cemented and plastered, blocking half of the late medieval traceried window and the west doorway, through which the laity would have accessed the church. The pointed trefoil motif of the tracery indicate a fourteenth century date, and indeed the priory register mentions benefactors William Canus and his wife giving money for the fabric of the front of the church sometime before 1324, year of his death.

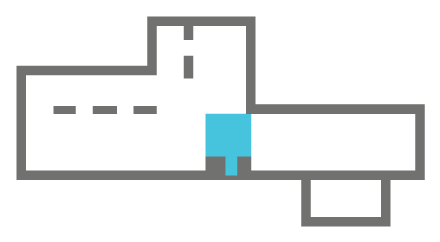

: A view of the remains of the tower built between the nave and the chancel in the fourteenth century. We know from the priory register that it was built up to the roof level before 1344, and completed by burgess Jacob Lynch. All that remains are the south piers of the arches that would have supported the tower. Through the recess formed by the piers, a now blocked doorway - which probably existed before the insertion of the tower - would have given access to the friars from the church into the cloister walk.

A view of the remains of the tower from the lateral aisle, showing how the inserted tower cut through half of one of the nave’s six lancet windows, which are identical to the lancets in the chancel.

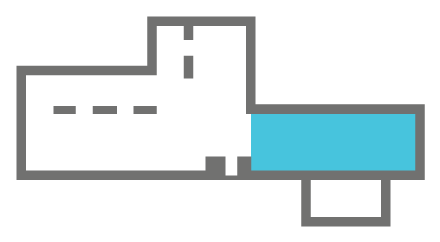

A view of the interior of the chancel. The division of the internal space is marked materially by three steps, between the friars’ choir, where the community would have sat in wooden stalls, and the presbytery to the east, the space reserved to the clergy celebrating the liturgy and where the high altar stood underneath the east window.

A closer look at the figure carved on the jamb of the altar tomb’s arch, a devotional image of a ‘Madonna with child’: an enthroned Mary holding Jesus as an infant.

This altar tomb is located in the north wall of the presbytery section of the chancel, and dates to the fifteenth century. It is a canopied tomb with a richly moulded arch that used to be filled with tracery, and is framed by pinnacles. The front of the tomb is composed of five panels decorated with ogee-headed arches. Perhaps it was the ‘sculpted tomb’ imported ‘from over the sea’ by Joanna Wffler for her husband’s burial; she was an important benefactor of the priory, giving more than 100 marks towards the glazing of the east window and all the windows in the chancel, funding the construction of a stone bridge between the friary and the town, and donating a wooden vestment chest, with silk and gold vestments.

A view of the south elevation of the chancel. There were originally seven pointed lancets, but the west-most window was blocked by the addition of the north transept, cutting it in half. Based on the priory register and analysis of the fabric, it was suggested that the original chancel was extended by about 20 feet to the east by William Canus and his wife in the early fourteenth century, although some have contested that claim. Interestingly, the three steps separating the presbytery from the choir in the chancel are placed just 18 feet from the east gable.

An external view at the east gable of the chancel. The east window is a four-light with switch line tracery. It is a later insertion dating to the fifteenth century, placed within the larger arch of the fourteenth-century window, of which small segments of tracery remain encased in the later fabric. The original window had five lights, and its tracery included pointed trefoil motifs indicative of a fourteenth century date.

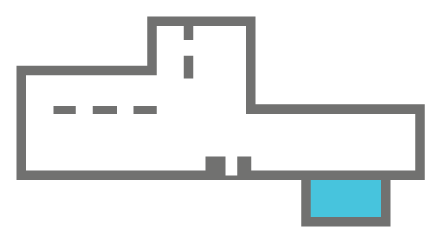

The sacristy is located to the south of the chancel, and accessed through a pointed doorway. It was either rebuilt or refurbished in the Early Modern period, as suggested by this triple light ogee-headed window in its east wall, but there is some architectural evidence that the building originates in the Middle Ages.

A view of the north elevation of the church. It stands within a graveyard that is not in use anymore, and the main access is through a doorway in the north transept. It is locked and the key is with a caretaker that lives nearby.