Ennis Franciscan Friary

Add to favorites

Add to favorites

Order: Franciscan (OFM/ Ordo Fratrum Minorum)

Founded in the mid-13th Century

Founded by a member of the O’Brien lords of Thomond (Uí Bhriain)

Also known as: Inis Cluana Rámhfhada (Clonroad)

The Place

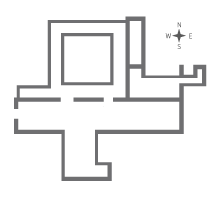

Ennis Franciscan friary was built on an island at a point where the river Fergus divides. This island is now incorporated into the streetscape of the modern town but remnants of the medieval settlement are evident. Apart from the friary, traces of the O’Brien medieval residence and late medieval houses are scattered throughout the town and it is clear that the friary was deliberately located at a crossing over the river into the settlement. It also benefited from river fisheries. The original O’Brien founder of the friary is unknown – it may have been Donnchadh O’Brien, king of Thomond (d. 1242) but no records survive. The friary appears to have been endowed and re-constructed in the late thirteenth century by a later king, Toirdhealbhach O’Brien (d. 1306) and it was used as the burial place of the O’Briens and the MacNamaras (Mac Conmara), the other powerful lords of the region. Much of Ennis friary survives intact including its very fine stone carvings, now exhibited in the recently refurbished nave of the church.

The People

Ennis friary was one of a series of Franciscan friaries that benefitted from O’Brien patronage between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. The fourteenth-century heroic tale Caithréim Thoirdhealbhaigh ‘The Triumphs of Toirdhealbhach’ tells how Toirdhealbhach Ó Briain, king of Thomond supplied the friary with sweet bells, holy crucifixes, a good library, embroidery, glass windows of blue glass, veils and cowls. Under O’Brien patronage the friary flourished as a school for novices (studium) and also as a foundation that attracted accomplished sculptors. In 1375 two friars from Ennis were sent to study in the Franciscan studium in Strasbourg and an Irish lector in theology was appointed in 1441. The late fifteenth century was a particularly active period of building at Ennis. A bell tower was inserted and the south transept was added to the church. Conor na Srón O’Brien (d. 1496) and his daughters were particularly associated with the Franciscans. Conor had led a particular violent life and appears to have fathered two sons with his daughter Renalda who was the Augustinian abbess of the nearby convent of Killone and who herself was buried in Ennis friary (d. 1510). His other daughters, Nuala and Margaret, were patrons of Donegal and Dromahair friaries. On his deathbed, Conor feared his final judgement but Friar Fergal O’Trean, a saintly Franciscan preacher of Ennis, agreed to take on the burden of the chieftain’s sins given all the favours he had stored in heaven due to his good works. Miraculously after Conor died, according to a seventeenth-century legend, his soul was seen entering heaven borne there by the preacher’s prayers.

Why visit?

A beautifully executed series of carvings were added to the church in the fifteenth century as part of a devotional cycle that introduced the laity to the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. St Francis displaying his stigmata (the impression of the wounds of Christ on the cross) was placed to the left of the great rood screen while to the right was a carving of Christ as the Man of Sorrows surrounded by the Instruments of the Passions. A broken statue of a Pietà, the sorrowful Mary with her dead son lying across her lap, is one of a number of Irish examples of this popular medieval image which caused the laity to experience the suffering of the Virgin and to be grateful to her for offering up her son for the salvation of humanity. The MacMahon-Creagh tomb, said to have been commissioned by Máire O’Brien/MacMahon around 1470, narrates the scenes of the Passion: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, the Crucifixion, the Entombment and the Resurrection. A woman in a panel beside the Resurrection holds a book and is dressed in contemporary clothing including an impressive headdress. This may be a depiction of the donor, Máire O’Brien holding a Book of Hours. The sequence of images on the tomb suggest that this was an Easter sepulchre, a representation of Christ’s tomb which would have been placed to the left of the main altar and would have been a focus of the Easter ceremonies when the general laity were given the rare opportunity to pass through the rood screen from the nave to the chancel.

What happened?

1250: Possible foundation of Ennis friary under O’Brien patronage in their medieval settlement.

pre-1306: The friary extended or re-constructed and decorated by Toirdhealbhach O’Brien, king of Thomond.

1375: Two friars from Ennis were sent to study in Strasbourg.

1441: Friar Thaddeus MacGillacunduin was appointed lector of theology.

1460: Ennis friary reputed to have accepted the Observant reform (see 1540).

1491: The Ennis friars lost their case against the friars of Askeaton (Co. Limerick) in a dispute over the limits of each friary’s area for seeking alms (known as questing).

1496: Conor na Srón (meaning ‘the nose’) O’Brien was buried in the friary having been ministered on his deathbed by Friar Fergal O’Trean, a saintly preacher in the friary.

1540: Observant reform accepted in the friary.

Post-Dissolution: the Franciscan friars have maintained a presence in Ennis to this day.

1570: The friars were still in Ennis, despite the friary’s official suppression in 1543, restoring the faith to Cornelius O’Brien in this year.

1577: The friary was first granted to Dr Daniel Neyland, rector of Inniscattery in the Diocese of Killaloe, then later that year, to Conor O’Brien (d.1581), 3rd earl of Thomond (mistakenly called earl of Ormond in Gwynn & Hadcock).

Late 16th century: A Protestant Bishop of Kildare was reported to have been buried in Ennis friary, where his ancestors had been buried. The friars were unhappy with the marble monument erected in the friary church but could not prevent the burial. However, a few days later, a number of friars disinterred the bishop in the dead of night and buried him in a ‘foul and squalid hole outside the town’.

c.1617: The friary was noted as being in very good condition, primarily down to the care of Donough O’Brien (d.1624), 4th earl of Thomond. Despite being a Protestant, O’Brien maintained the buildings, using part of the friary as a court and lodgings but not altering the fabric of the buildings. An old friar was allowed remain in Ennis wearing his habit and say mass in his bedroom

Again in 1617, Donough O’Brien, 4th earl of Thomond was recorded as possessing the gold and silver plate belonging to the Ennis Franciscan community. However, O’Brien had converted these chalices to his own uses. The contemporary Franciscan chronicler Donatus Mooney suggested that this had been done to ensure the safety of the objects and was confident that they would be returned by the earl or his heirs to the friary. No altar plate has been uncovered that is connected with the friary, suggesting that Mooney’s faith might have been misplaced.

1621: The buildings were converted for Protestant worship.

1628: The friars returned to Ennis friary.

The is an interesting story recorded as part of the Dúchas Schools’ Collection about a chalice found in Salach Bhuaile Lisroe, Kilmaley, near Ennis. In 1920 John Boland, a local man in his 80s, told the local priest, Rev. Roche about a “pretty” chalice his father had seen in the mid 19th century. It had been discovered buried near Salach Bhuaile beside a pyx which contained a withered host. The story went that when a hedge schoolmaster was in the area, he stole the chalice and “sold it to the Protestants.” In the 1930s, there was a chalice in the possession of the Ennis Protestant church known as the ‘Kilmaley chalice’, although whether these were one and the same, we’ll never know.

(from The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0608, Page 451, www.duchas.ie accessed 21st October 2016)