A view of the church south elevation, showing the modern cemetery.

A view of the exterior eastern façade of the church, and of the exterior of the east range.

A view of the church west and south elevation. The laity would have entered through the west doorway into the nave; it is unsure why there is another doorway in the south wall.

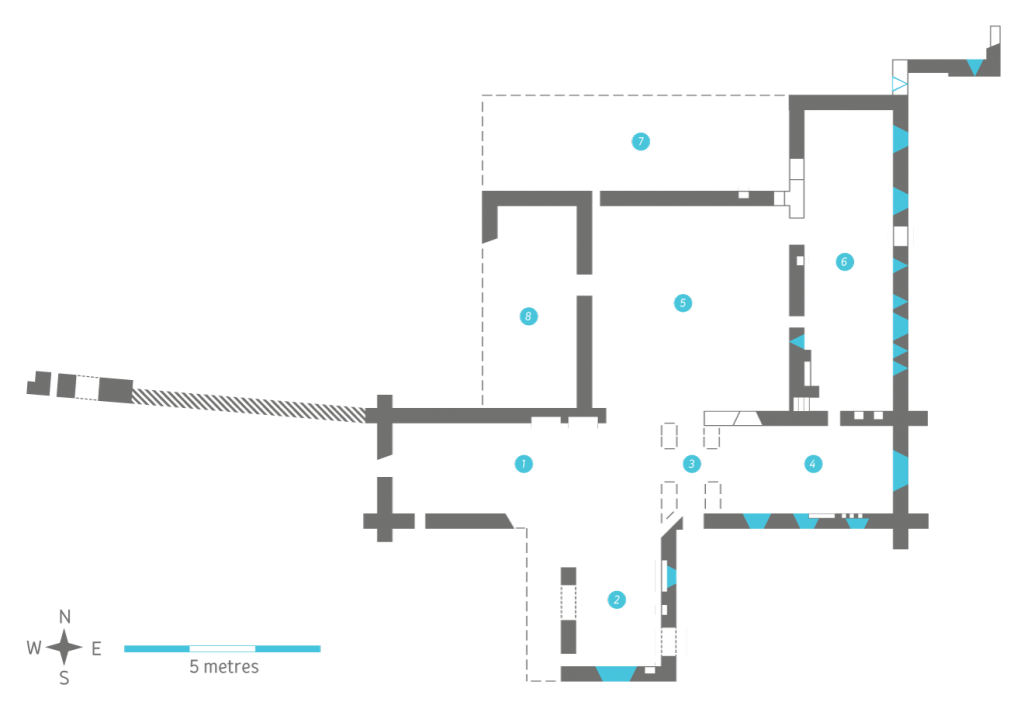

A view of the interior of the church, from inside the nave, looking east towards the chancel and the traceried east window. Although there is no more standing internal division between nave and chancel, a crossing tower used to delimitate the space. Its position can be gaged from foundation scars just beyond the two tomb niches in the north wall, amidst the many modern burials filling the church.

This is one of a set of two tomb niches at the east end of the nave north wall, placed just before where the crossing tower would have stood, a very common place to find burials in a mendicant context. These two examples are rather typical of fifteenth-century tomb niches found in a number of Franciscan friaries of the west of the country, characterised by an ogee-headed hood-moulding and ornamental pinnacles on each side. Similar types of tomb niches can be found in Quin, Adare, Askeaton, Ennis, and Kilconnell Franciscan friaries.

A view of the exterior south elevation of the south transept of the church, a four graded lancets with slim mullions, grouped under a pointed arch.

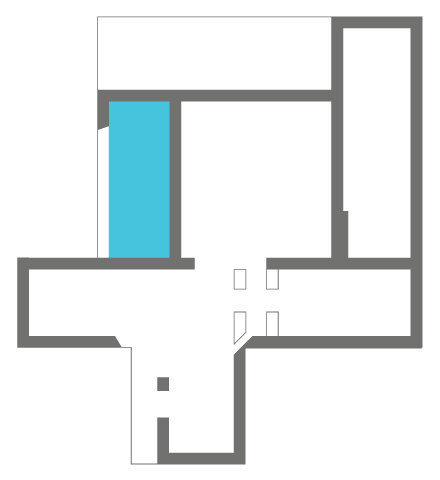

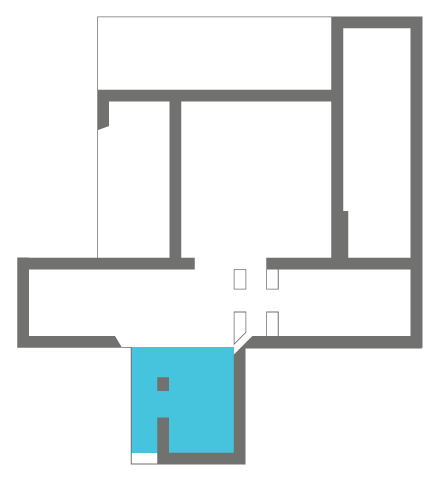

The south transept or south chapel remains in a rather ruinous state, although the south window tracery survives almost complete. It would have originally contained a western aisle, separated from the main space of the chapel by an arcade. To the fore-front of the picture to the left is part of the foundations of the west elevation of the crossing tower, the plan of which suggests that a passage was accommodated from under the tower to the south transept, allowing the friars to reach it without going into the nave.

A view of the church east window, a four-light with simple curvilinear tracery.

An exterior view of a window in the south wall of the chancel.

A close-up of the decorated carving, depicting stylised foliage, in the spandrel between the arch and the square hood-moulding and beyond the hood-moulding to the right.

The decorated carving on the left spandrel of the south wall of the chancel.

(A spandrel is the triangular space on the outer curve of an arch)

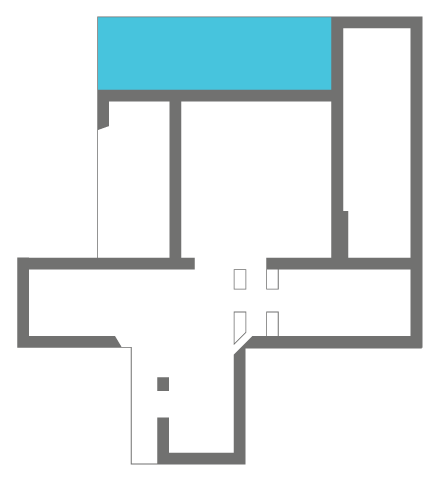

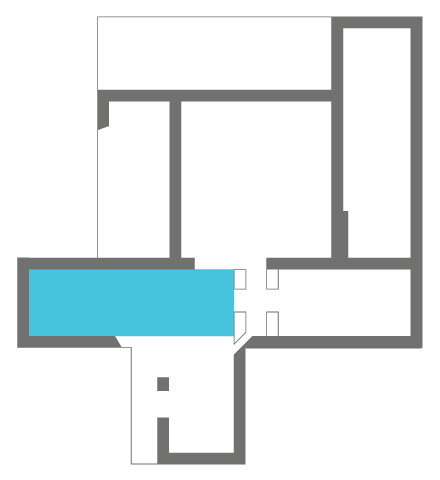

A view into the chancel. It would have originally been divided into two main spaces:

the choir, where the friars would have sat, probably in wooden stalls, just beyond the crossing tower, and the sanctuary or presbytery, where the high altar stood against the east wall and where the friar celebrant would have given mass.

The sedilia were the seats used by the celebrant and his two assistants during the office. This is a beautiful fifteenth-century example with three pointed arches with roll and fillet mouldings resting on chamfered jambs with moulded capitals and bases, grouped under a square hood-moulding.

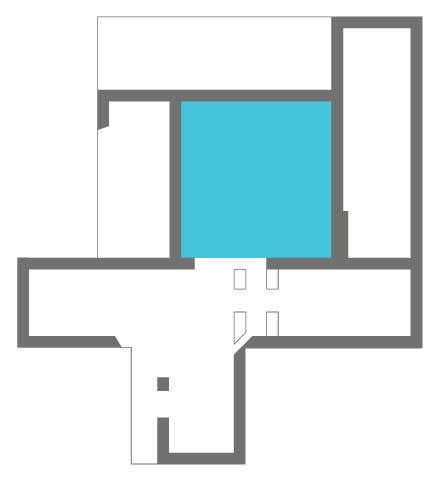

A view into the cloister square. The cloister arcade and ambulatory have all but disappeared, and the ground is used for modern burials; like the rest of the friary it has basically become part of the modern cemetery.

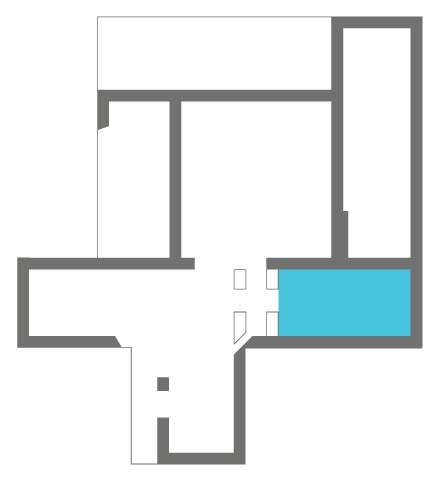

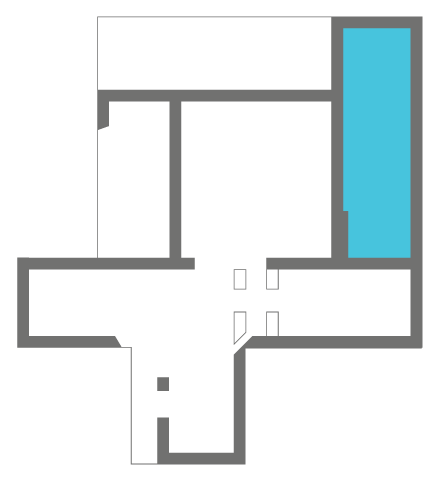

A view into the east range of the domestic buildings, the only one still standing.

A view of the south wall of what probably was the friars’ lavatory building, just off the east range.