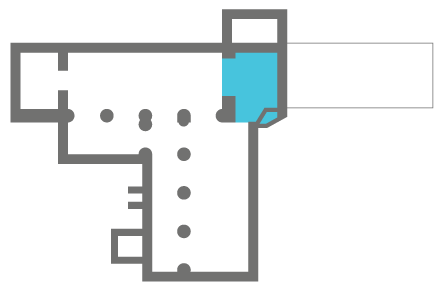

A view of the Dominican church fourteenth-century nave, south transept and their lateral aisles, restored as part of the modern church. At the intersection of the nave and transept is a sixteenth-century tower, which used to stand between the nave and the choir. The latter fell into ruins and at the end of the eighteenth century its stones were used to build living quarters for the Dominican friars.

A view of the east elevation of the transept and the tower, which is now the east end of the church. In addition to the large south window in the church transept, the four windows in its south elevation, seen here, as well as the four in the north elevation of the nave, are all restored fourteenth-century triple-lights with Decorated Gothic geometric tracery.

Just outside the church entrance, a number of medieval stone coffins and slabs are displayed along the wall. They were discovered during the nineteenth-century restoration work undertaken in the church.

A closer look at one of the medieval century stone coffin, the effigy tomb of a woman.

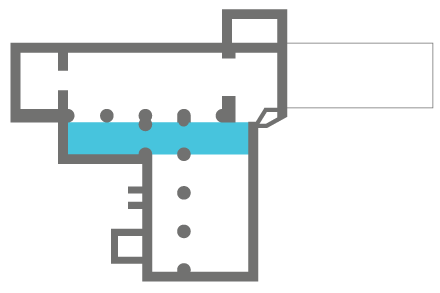

The fourteenth-century nave and aisle, separated by an arcade of pointed arches. The nave was restored after the transept, and re-consecrated in 1864. It was rebuilt with the stones from the living quarters that had been built for the friars at the end of the eighteenth century, which themselves had been partly constructed with stones from the ruined choir of the church.

A view into the nave, looking east. The church crossing tower, which would have originally stood between the nave and the choir, became the sanctuary when the church was restored for worship in the nineteenth century. The ruined choir had been pulled down a few years earlier, its stones used to build new living quarters for the friars. The new east window was inserted in the tower east arch, and modelled after the fourteenth-century transept window, with similar Gothic-inspired tracery.

In the south gable of the transept is a large five-light window taking up nearly the entire width of the wall. It is the largest of its kind in Ireland, and is decorated with cusped switch-line or intersecting tracery with motifs belonging to the geometric phase of Decorated Gothic, such as quatrefoils. It is known as the ‘Rosary Window’, and the stained glass was created in 1892.

The 'Rosary Window', completed in 1892 and donated by a Mr Hudson in memory of his wife, was glazed by Mayer & Co. of Munich, specialists in architectural stained glass and mosaic, still active today after 170 years as Franz Mayer of Munich

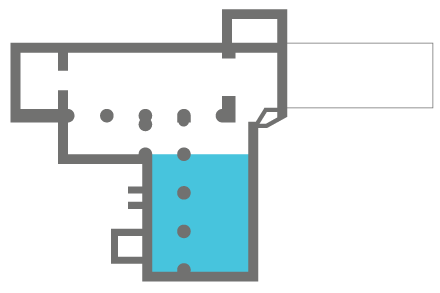

A view into the fourteenth century transept. The length and width of the transept is remarkable, as it would originally been roughly as long and wide as the nave (it is now longer). It was built to accommodate the growing crowds that came to listen to the friars’ preaching and to attend masses and celebrations in their church, as well as the laity’s devotions and burials. Benefactors paid for chantry chapels and secondary altars dedicated to the cult of saints where the friars would pray for their souls, and where they could also be buried.

Kilkenny was a large and wealthy city and the friars were very popular amongst the population, which explains why a structure of such size was built to accommodate the pious donations and the burials of the friars’ many patrons.

A closer look inside the tower at the sanctuary of the modern church, with the high altar placed in front of the west tower arch, and the east window inserted in the eastern arch.

This sculpted representation of the Trinity, carved in alabaster, was discovered during the restoration work of the early nineteenth century.

It is kept in a glass case attached to the central tower, and has been estimated to date back to c. 1400. A fourteenth-century limestone figure of St Catherine of Alexandria – protectress of the Dominican order – was also found, and is on display in the priory museum.

This alabaster carving of the Holy Trinity bears the inscription '1264' on the base but it is believed to have been carved in Bristol c.1400. The earlier date was reportedly added in the early 19th century for reasons unknown.

Standing roughly 82cm high, the delicacy of its carving the piece belong to a small number of large-scale English alabaster figures which survive.

It would have been originally painted and gilt.

A view of the east elevation of the church, with the large fourteenth-century transept standing to the south of the sixteenth-century tower, which was once described by architectural historian H. G. Leask as ‘the most perfect’ of all surviving square-plan towers in Ireland.