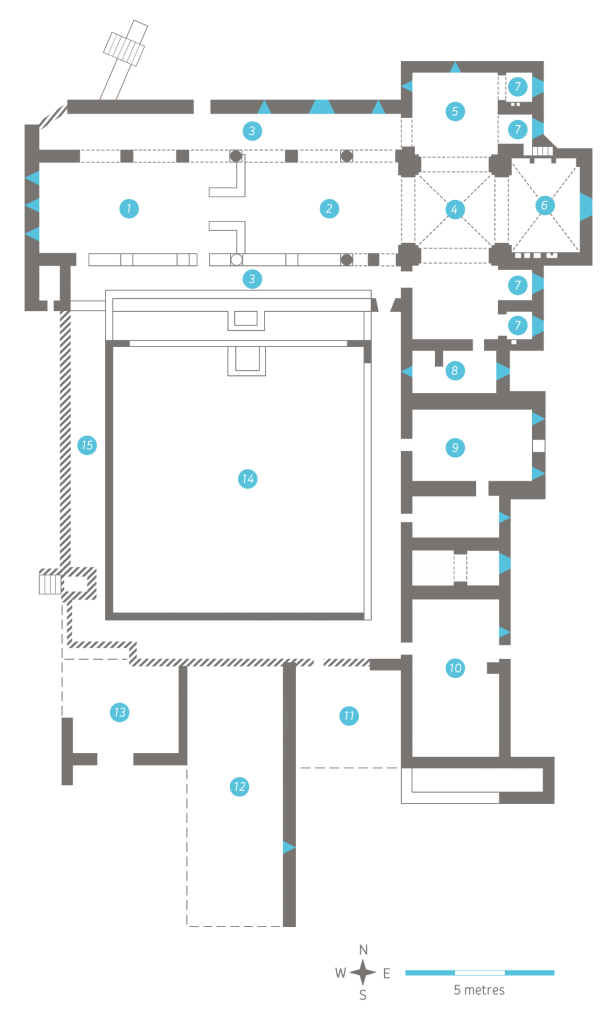

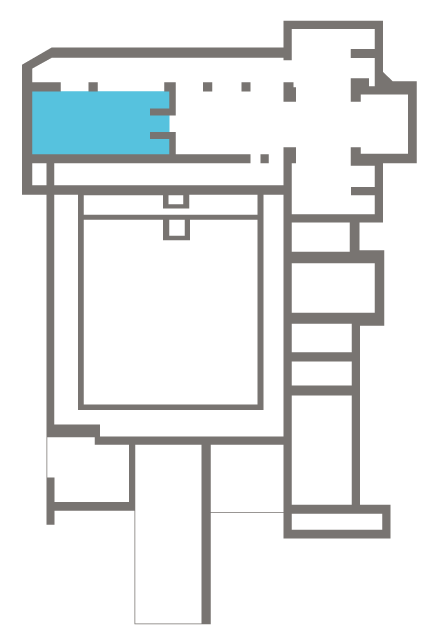

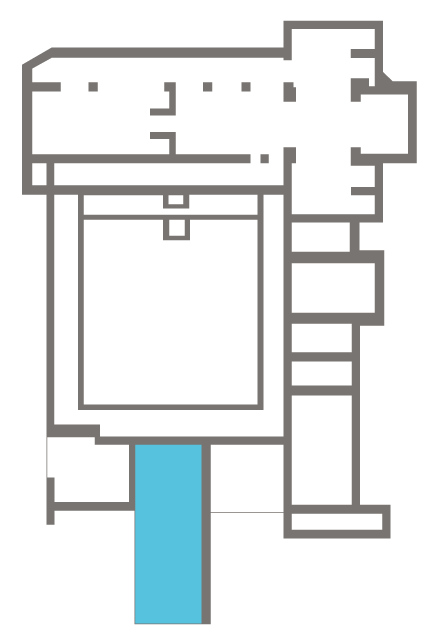

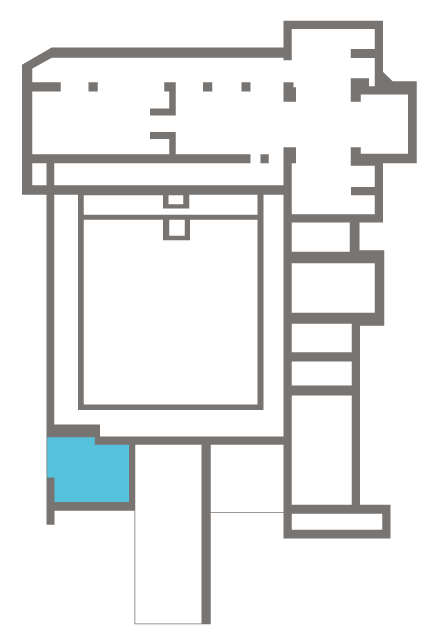

A view of the western half of the nave, reserved for the lay brothers of the monastery. The window in the west wall is a group of three simple round-headed lights, typical of Cistercian Romanesque in Ireland.

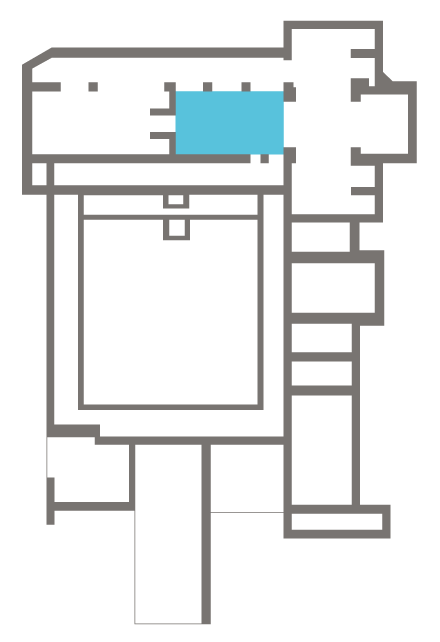

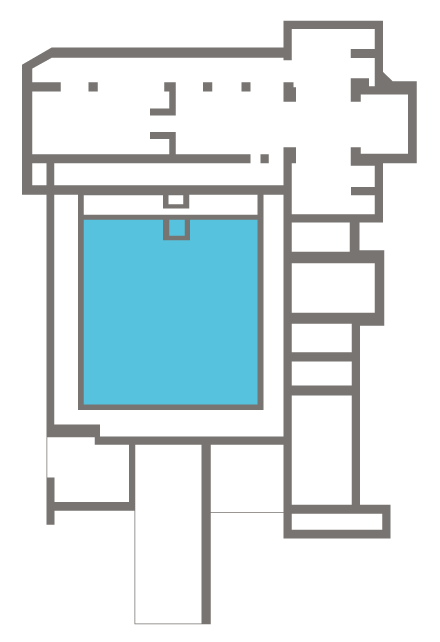

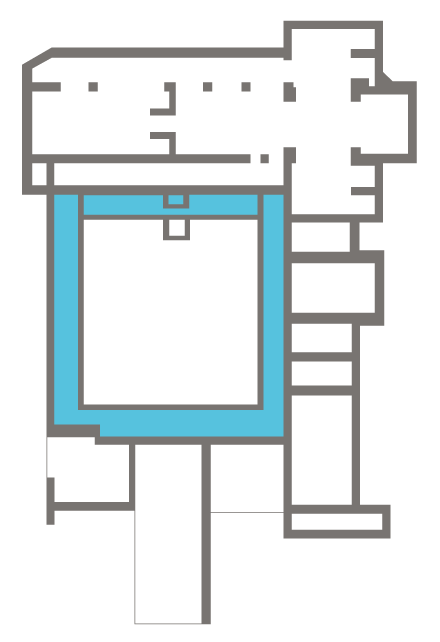

In keeping with the Cistercian ethos of austerity the nave is almost devoid of sculptural decoration. The slightly peculiar positioning of the windows over the piers in the nave betrays the influence of masons from the west of England, where this design was more common.

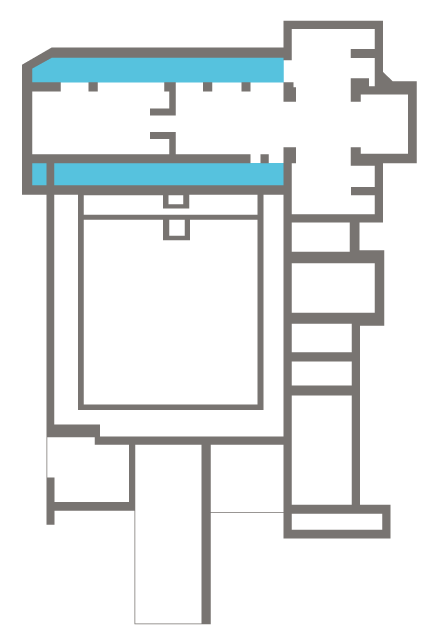

The nave at Jerpoint originally had an arcaded aisle on both side. The low ‘perpyn’ wall, mid-way down the nave marks the transitional point between where the monks (to the east) and the lay brothers (to the west) prayed.

This column is the only one that remains from the arcade that separated the nave from the southern aisle. Unlike the columns capitals in rests of the nave, decorated with simple scalloped edges, this one, on the east-most column of the monks’ choir section of the nave, is adorned with more elaborate Romanesque motifs.

Detail of the decorated capital of the sole surviving arcade column

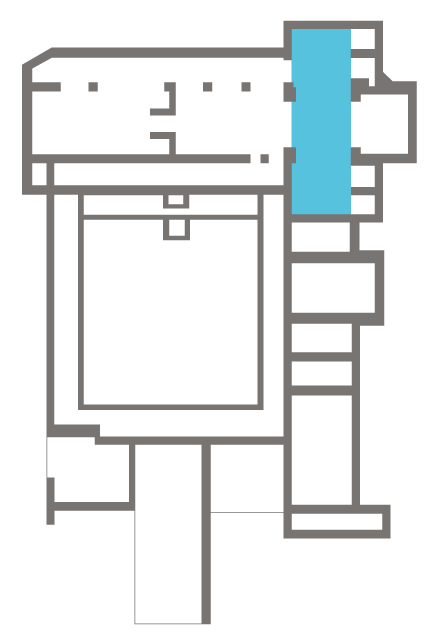

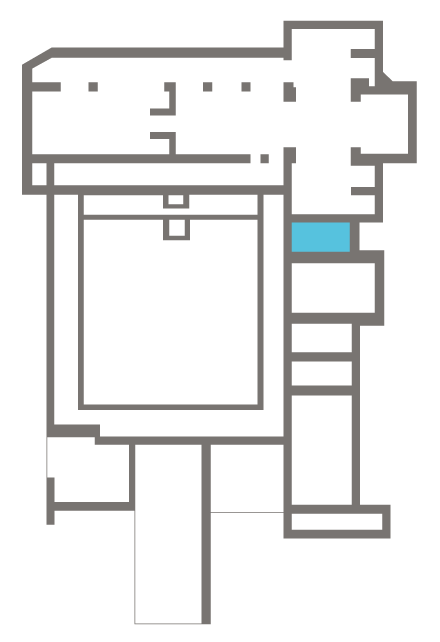

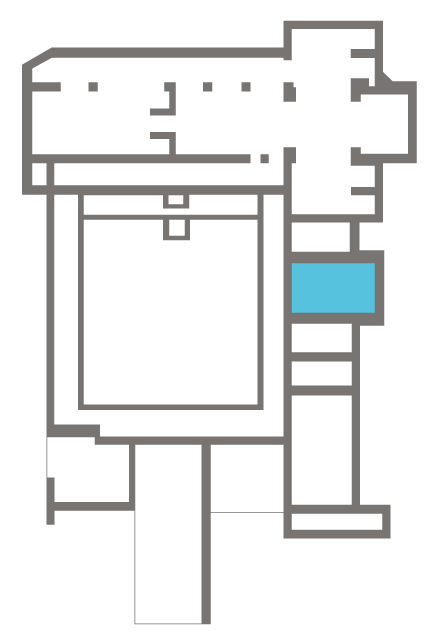

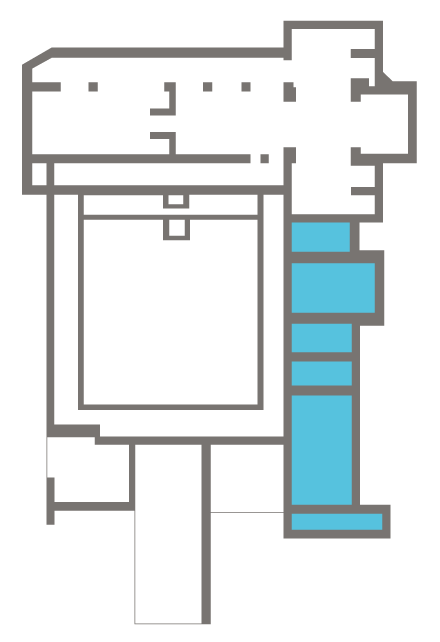

A look at the archway opening onto the south aisle, from the transept. Directly to the left of the arch is the modern staircase where the original night stairs the monks used to come down from their dormitory into the church at night would have been.

A look in the north aisle of the church, separated from the nave by an arcade of pointed arches supported by large circular and square piers, with capitals decorated with scalloped edges, a typical Romanesque motif used in Irish Cistercian abbeys.

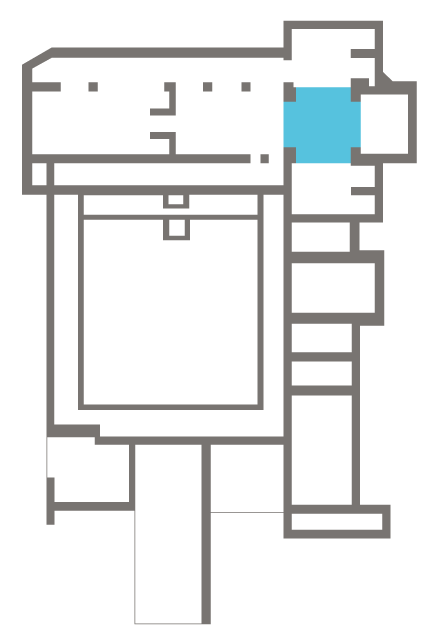

The crossing tower built above the intersection of the chancel, nave and transept was added in the fifteenth century. Crossing towers were not originally allowed by the order’s governing authorities. In architectural matters, the order encouraged austerity and simplicity, with no decorations and no bell towers, following the model of Fontenay Abbey, in Burgundy, the first abbey founded by Bernard de Clairvaux after he established the Cistercian order in the early 12th century.

A look at the ribbed vault supporting the crossing tower. The tower has a perfectly square plan, supported on each side by pointed arches that open onto the nave, the chancel, and both transept arms.

This tomb, now reassembled in the crossing of the church, has a lengthy inscription that grants remission of time in Purgatory for those who pray for the souls of Walter Breathnach (Walsh) and Katherine Butler.

This floor slab covers the table tomb bearing the inscription that commemorate Walter Walsh and Katherine Butler. It was the burial slab of Robert Walsh of Castlehale (d. 1501) and his wife Katherine Poher.

This slab commemorates Edmund Walsh of Castlehale, Co. Kilkenny, and his wife Johanna le Botiller (Butler), and is placed underneath the crossing tower. Edmund’s family had been benefactors to the abbey. He is the father of Walter Walsh, whose own burial slab is placed on the table tomb also located underneath the crossing tower.

A view of the south arm of the transept, showing the arches opening onto two transeptal chapels in its east wall. The original plan of Jerpoint abbey (without the crossing tower), followed exactly the model established by the Burgundian abbey of Fontenay: a cruciform plan with two lateral aisles, a flat apse (the east gable of the church) and two chapels at the east end of the transept arms, also with flat east walls. In the south wall of the transept arm is the doorway into the sacristy.

A view into the transept of the church, showing the crossing, the section of the transept where it intersects with the nave and the chancel. The funeral slabs placed under the crossing commemorate benefactors of the abbey who were buried within the church.

This view, looking into the south transept of the church, shows the door that led from the dormitory, down the night stair (a modern replacement) directly into the church, leaving the monks with no excuse to miss their nightly and early morning prayers.

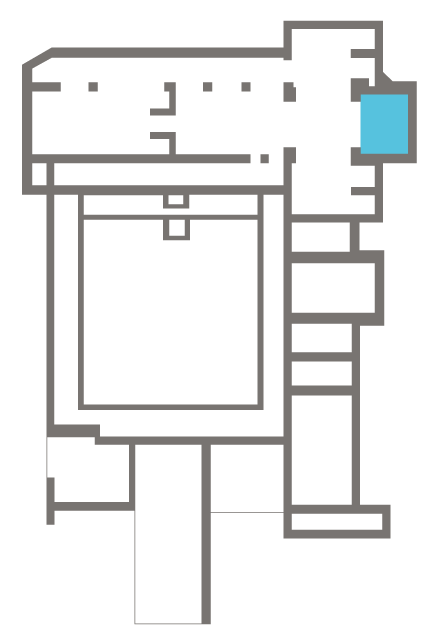

In contrast to the nave, the pier capitals in the transept and presbytery are carved with abstract, Romanesque motifs.

A view of the interior of the presbytery, showing two tomb effigies, one of them of twelfth-century bishop of Ossory Felix O’Dulany, who was also the first abbot of Jerpoint (d. 1202). Hi tomb used to be set within the east-most of the three tomb niches in the north wall of the presbytery, seen here behind the effigies.

This memorial effigy in the presbytery is said to represent Felix O’Dulany, the first Abbot of Jerpoint, who became bishop of Ossory in 1178 and died in 1202. It has been restored and moved to its current position during conservation work, but was originally lying partly under the east-most tomb niche in the north wall of the presbytery, which can be seen in the background of the picture here.

This is another effigy of an ecclesiastical figure, also a bishop, possibly Donal O’Fogarty, bishop of Ossory at the time of the foundation of the abbey, who probably assisted in its establishment.

The three arches in the south wall of the presbytery appear to be a very early example of a sedilia- seats for the clergy officiating at Mass. To their east (left in the photo) is a piscina – a basin used for washing the Mass vessels.

A new east window, with quite elaborate tracery, was inserted in the east end of the church, probably in the fourteenth century. The scar of the earlier, small Romanesque windows can still be traced in the gable outside.

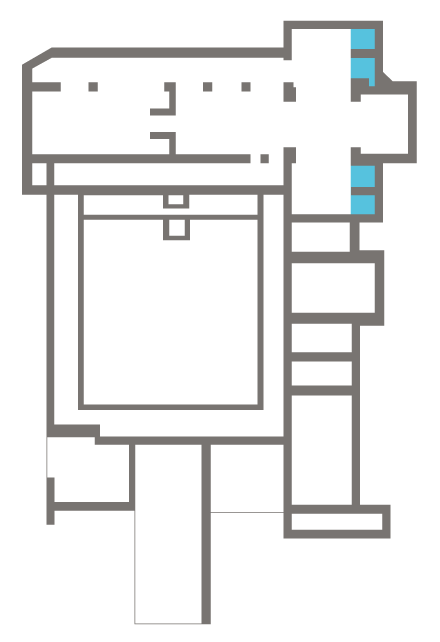

The abbey at Jerpoint is unusual among Cistercian abbeys for its collection of tombs. This one, in one of the two chapels in the north arm of the transept, is decorated with figures of saints and apostles called ‘weepers’, attributed to the ‘O’Tunney’ carvers of the early sixteenth century.

On the front of the tomb are St Peter with a key on the left, St Andrew in the middle with a saltire cross and St James with a Pilgrims hat on the right.

On the side of the tomb are St John with a Chalice, St Thomas with a lance, St Simon with a saw, St Bartholomew with skin (he was flayed), St Paul holding a sword, and St Matthew an axe.

A closer look at the tomb in one of the two chapels in the north arm of the transept.

The carved ‘weepers’ on the front of the tomb are St Michael the Archangel in the centre, St Catherine of Alexandria with a wheel on the left, and St Margaret of Antioch on the right. St Margaret wears a ring broach

The three figures on the side of the tomb are St James the lesser, St Philip, with a Latin cross, and St Matthias with a sword.

A view of the upper floor of the east range, where the monks’ dormitory was located. To the north of the room on the left is the doorway that would have led down into the church by the night stairs, allowing the monks to quickly reach their choir during the nightly prayers of the liturgy of the hours.

A view into the lower floor space at the south end of the east range. It probably housed a day room, where the monks would have assembled for a variety of activities, and perhaps also the novice’s room, where those wishing to join the religious community spent their period of training and tutelage under the care of the Novice Master.

Another view into the lower floor of the east range, with what was probably the day room at the south end, and just before it a sort of passage or parlour, the two side walls of which can be seen in the forefront of the picture.

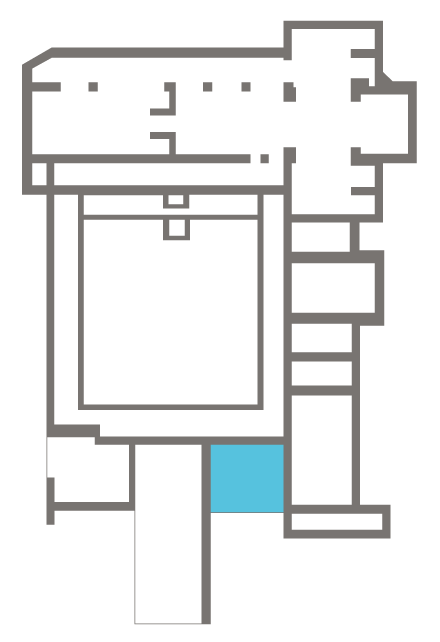

The buildings of the south range are mostly gone, but their foundations have been uncovered during archaeological excavations. The only section of wall that survive to some extent, and which can be seen here beyond the southern side of the cloister arcade, is the east wall of the refectory, which in a Cistercian monastery extended perpendicularly to the range. On either side of it were the calefactory or warming room, and the kitchen.

The cloister garth is marked by an arcade which would have supported a lean to roof on the four sides of the domestic buildings, and is composed of round-headed arches resting on couples of circular colonnettes. Every three arches are rectangular piers. Only the south and west sides of the arcade survive, included parts that were reconstructed by the OPW in the 1950s. Jerpoint cloister arcade is exceptional in Ireland for its highly carved colonnettes and capitals, presenting an array of human figures, lay and religious, grotesque figures, animals and monsters.

A view of the north side of the cloister walk, running around the cloister garth and which would have been covered by a lean-to roof supported by a fifteenth-century arcade of which the south and west sides remain.

Closer look at a figure on the corbel of the south face of a pier, west side of the arcade.

Many of the carved details on the cloister defy explanation. This strange creature is best compared with the small marginal drawings sometimes found in medieval manuscripts that seem to be just there for decoration. It is located on a pier of the west side of the cloister arcade.

Closer look at the figure of an abbot, on a pier at the north end of the west side of the cloister arcade.

Carving of St Catherine on the north face of a pier at the south end of the east side of the cloister arcade.

Carving of the figure of a Knight, on a pier of the west side of the cloister arcade.