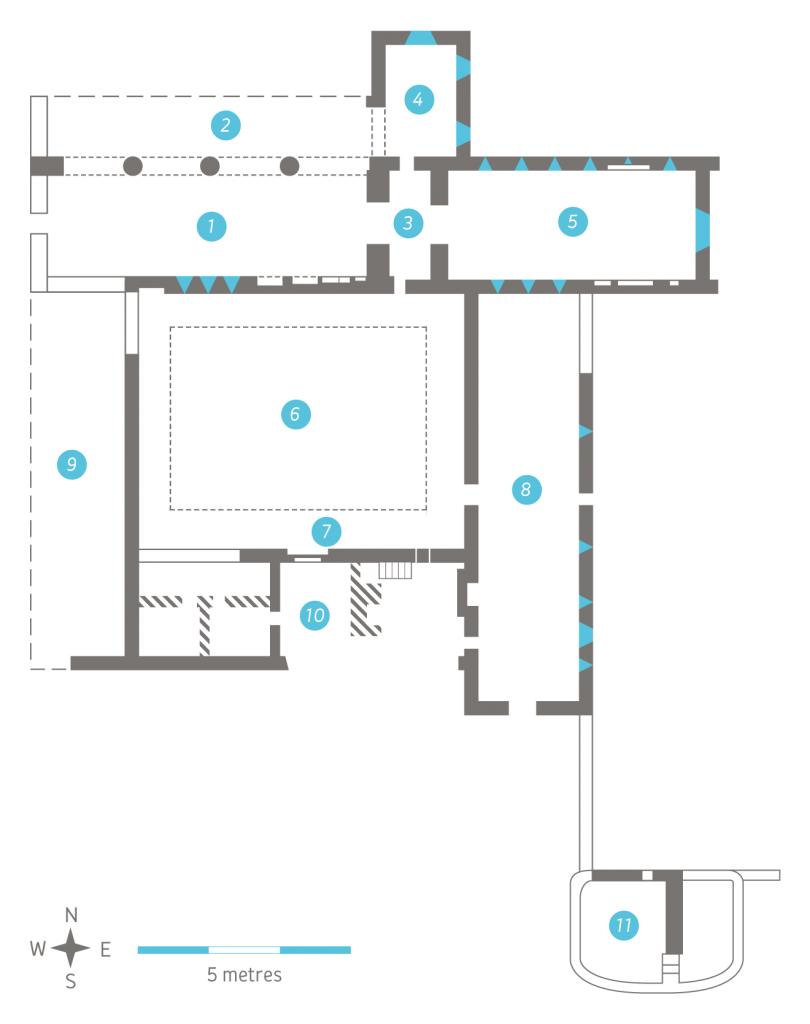

The windows in the south wall of the nave are original, but the north side was altered in the fifteenth century with the addition of an aisle. The tower marks the transition between nave and chancel, the area reserved for the friars. Its addition post-dates the construction of the aisle and some carving at the east end of the arcade suggest that a screen existed before the tower was inserted. The west gable of the nave is gone, but an eighteenth-century engraving shows that a four-light window similar to that of the chancel was inserted in the fifteenth century.

The existence of a secondary altar at the east end of the nave is indicated by the presence of a piscina in the south wall. The large corbel in the east wall originally supported the rood beam placed across the tower arch, which supported a large image of the crucified Christ. The smaller corbel, carved with a male head, probably held a statue.

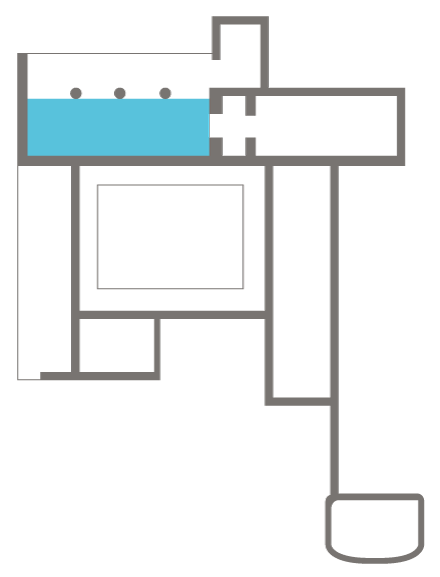

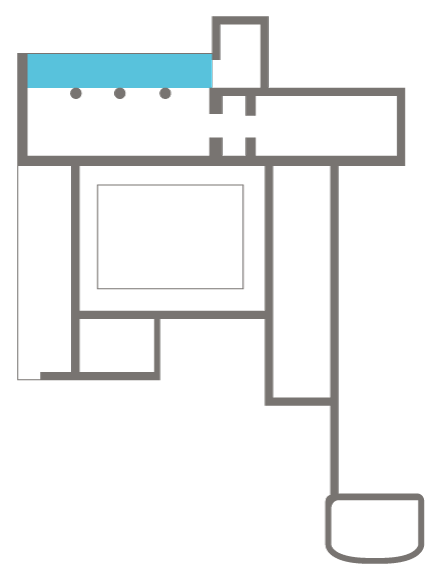

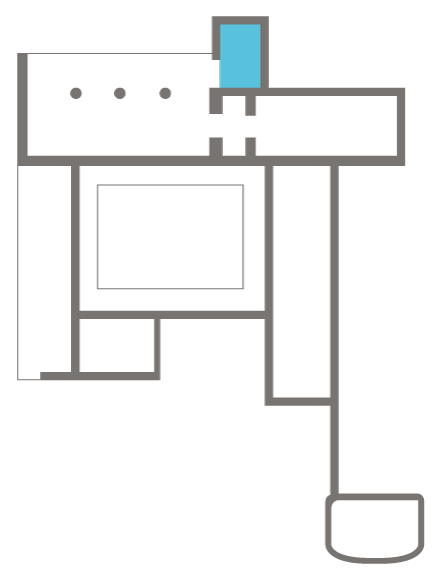

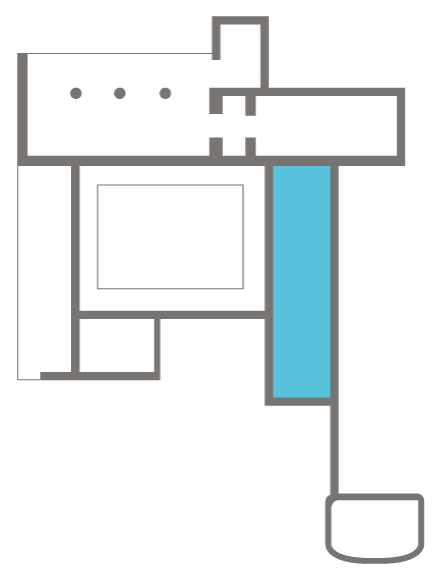

These three tomb niches are located in the south wall of the nave, close to where the secondary altar would have been placed at the east end of the nave.

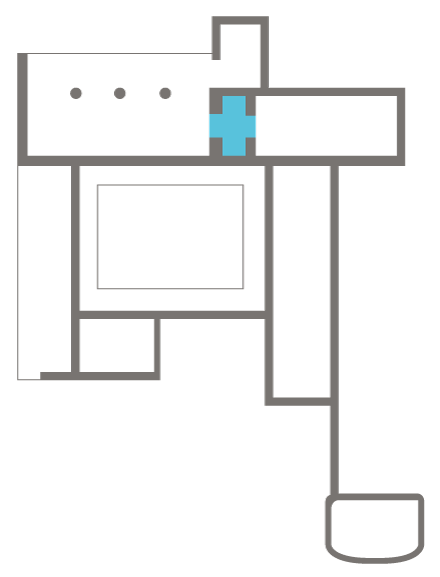

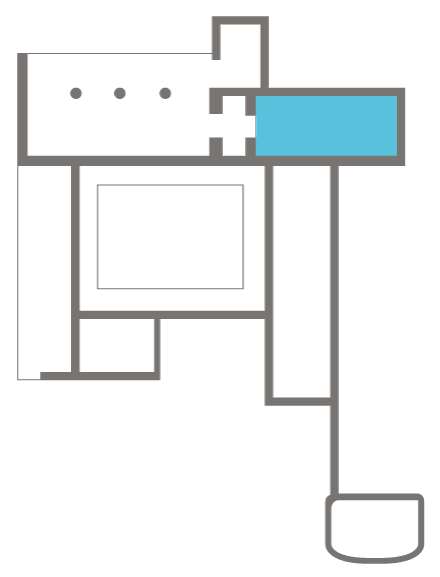

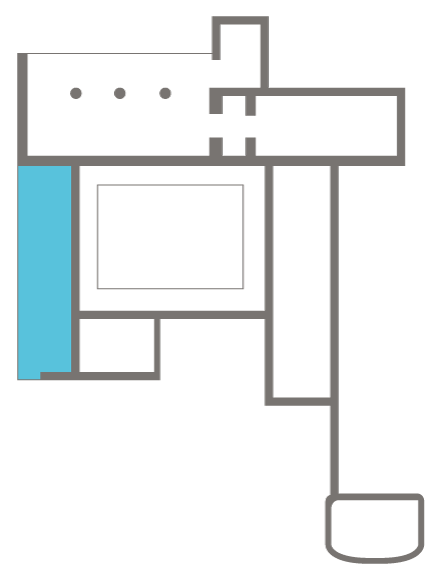

The skeletal arcade along the north side of the nave is all that remains of an aisle added to the church in the fifteenth century, to provide additional space for secondary altars and burials.

Another view of the north aisle, looking towards the north transept. Note how the hole around the central column of the aisle’s arcade indicates the rise of floor level due to centuries of burial practice within the church, both before and after the dissolution of the friary. The ground surrounding the remains of the friary is still used as a cemetery to this day.

These reassembled fragments placed between the nave and the aisle at the foot of the tower probably once formed part of the front of a thirteenth-century wall tomb, perhaps even one of the three located in the south wall of the nave.

The tall, elegant tower at Claregalway was built thanks to a papal grant of indulgences to those who contributed to its construction in 1433, and it rises to a height of more than 24 metres.

The central tower is rib-vaulted and at each of the four springing of the vault are small, figurative carving; one is too badly weathered to be identified, one is a human figure, and the other two, pictured here, are grotesque figures.

The central tower is rib-vaulted and at each of the four springing of the vault are small, figurative carving; one is too badly weathered to be identified, one is a human figure, and the other two, pictured here, are grotesque figures.

A view of the entrance to the north transept, taken from underneath the tower, which postdate both the transept and the lateral aisle added in the fifteenth century.

A view of the interior of the north transept looking towards the doorway that led into the chancel through the tower. The use of the transept as devotional and funerary chapel or chapels is indicated by the remains of a double piscina to the left of the door, while the trefoil-headed recess to the right likely housed a statue. Wealthy patrons would have made donations to be buried there and for the friars to pray and say masses for the salvation of their soul. The many modern grave slabs testify to the continual use of the space as burial ground.

Another view of the transept, looking through the archway that separates it from the north aisle. The triple light in the north gable is of the same style than the inserted window in the east gable of the chancel, indicating that the transept belongs to the same phase of structural and architectural additions commissioned sometimes in the fifteenth century, though it predates the construction of tower. In the eighteenth century, the transept was still roofed and used as a mass house.

The brightly lit chancel of Claregalway friary dates to the thirteenth century. In addition to the fifteenth-century east window, there are six thirteenth-century lancets on each side of the chancel The silhouette of the building was radically altered in the fifteenth century through the addition of the bell-tower.

A view of the interior of the chancel, looking towards the large, five-light east window, which is typical of fifteenth-century mendicant architecture in Ireland, with switch-line tracery and trefoil-headed lights. As is the case in other friaries, it replaces the earlier, thirteenth-century window, which was a group of three tall lancets that would have taken up most of the gable.

This finely carved tomb is in the north wall of the chancel, the location usually reserved for the founder or main patron, and is attributed to the De Burgo or Burke family. It is their coat of arms depicted on the memorial plaque placed within the arch of the tomb, bearing an inscription with the date of 1648.

The inscription

reads: Husc Incum sibi elegit Dus Tho Burgo de Anbally, Fils Richarde de Derrymaelaghni Anno Domini 1648

[Thomas de Burgo of Anbally, son of Richard of Derrymacloughney chose this place for himself, 1648 AD]

The elaborate tomb in the north wall of the chancel is framed by the carvings of two figures, a man and a woman. The latter is pictured here, represented with a fifteenth-century style of headdress. They can be assumed to represent the benefactors who commissioned the making of the tomb and would have also made donations towards their burial and prayers for their souls after they passed.

A closer look at the carving of a male figure, probably representing the benefactor who commissioned the tomb with his wife, also represented on the other side of the monument.

In the south wall of the chancel are the fragmented remains of a piscina and sedilia, which served the high altar.

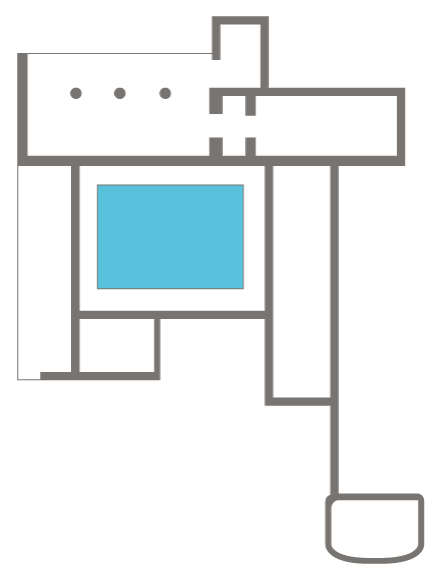

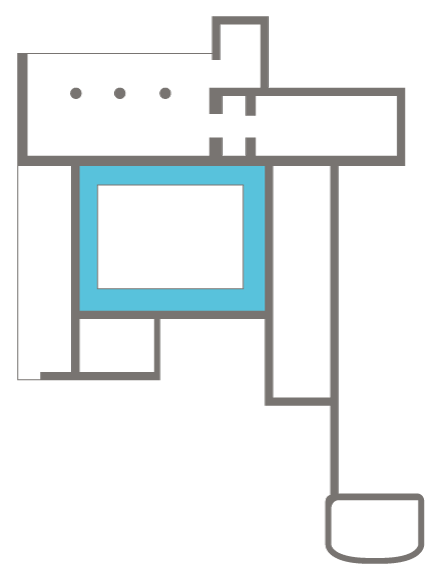

The outline of the cloister garth remains but the cloister arcade is gone, as his the lean-to roof that covered the cloister walk, though the string course and the corbels that supported it can be seen along the south wall of the church underneath the windows.

Another view of the cloister garth, showing the remains of the east and south range, with along the wall of the east range another set of string course and corbels that would have supported the lean-to roof covering the cloister walk.

A view of the east cloister walk, looking toward the entrance to the church, which the friars would have used to enter the chancel. Once the tower was built in the fifteenth-century, they would have had to go through it to do so, a common configuration in Irish mendicant friaries.

A view of the interior of the east domestic range, originally divided into a number of rooms, such as the sacristy and the chapter room. It is unusual that it obscures three of the lancet windows of the chancel, as the space where the domestic ranges abutted the church would normally be window-less, and it has been suggested that the range at that end was only one storey high. In the upper floor of the range the main dormitory of the friars was located.

A view of the interior of the east range, looking south. Small fragments of the cross-walls masonry remain and indicate that the ground floor of the southern half of the range made up one large room, which might have been the friars’ day room. The range was greatly altered over the years, including the addition of second floor, and of a large fireplace in the south wall of the first floor, modern in date. It is now used to store cut stones and fragments collected from the around the remains of the friary.

This wall is all that remains of the west range of the domestic buildings, which would have accommodated store rooms in its lower floor, and another dormitory, or a guest room in its upper floor.

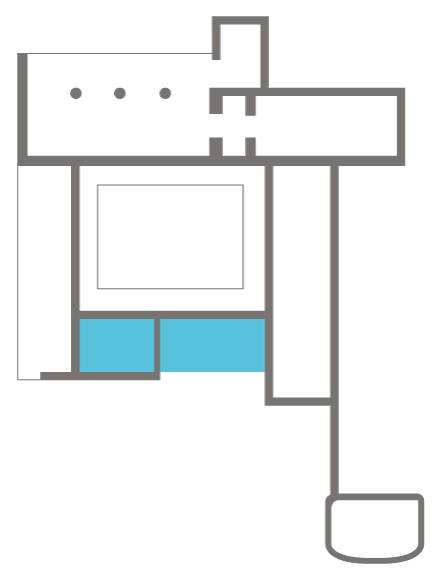

The now fragmentary buildings in the southern range of the cloister probably originally accommodated kitchens and the refectory. The internal walls and gables are modern additions.

Another view of the south range, which was greatly altered in modern times. As it is known that a few friars remained living in the friary up until the eighteenth century, it has been suggested they might have occupied that range only, and reorganised its interior accordingly.

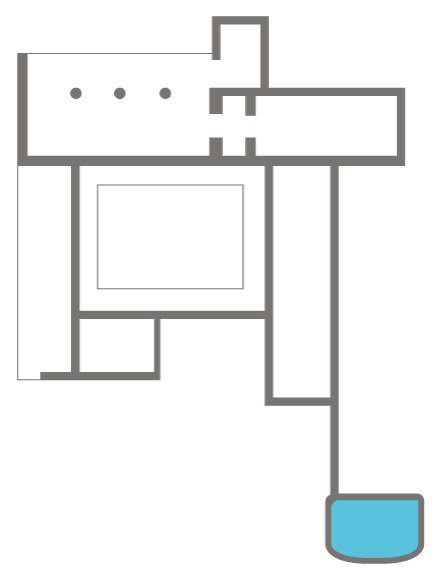

A view of the fragmented remains of what is believed to be the garderobe, or lavatory of the friars, and which is located a few metres south of the three domestic ranges. In the distance is Claregalway castle.