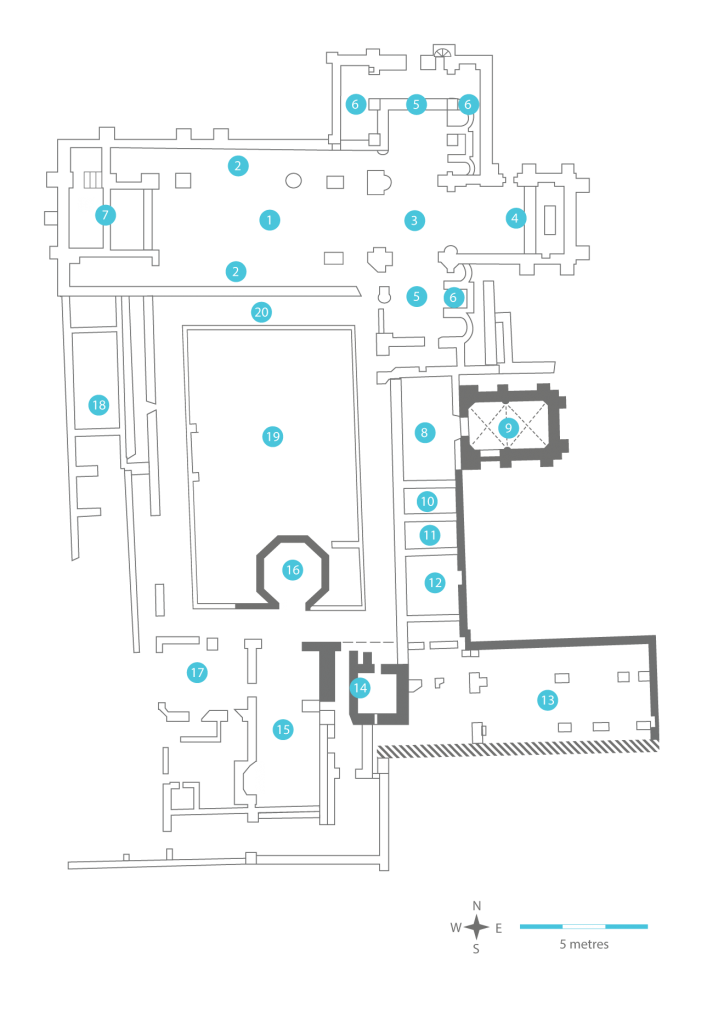

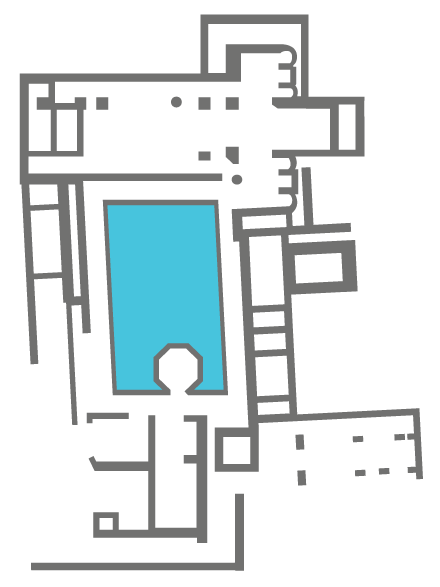

This picture was taken within the nave, looking towards the chancel. Very little standing remains are left of the nave. Less than half of the piers that separated it from the lateral aisles have left any trace. In Cistercian churches the monks’ choir was usually located within the crossing (the intersection of the transept and the chancel), and the east end of the nave, the rest of the nave being used by the lay brothers.

A view of the church, looking east. The two aisles on either side of the nave can be seen here. They were separated by rows of piers, very little of which remain.

A view of the crossing, looking towards the nave. The monks’ choir was partly located within the crossing. In the later Middle Ages, a tower was added over the crossing, at which point the piers were enlarged in order to support it.

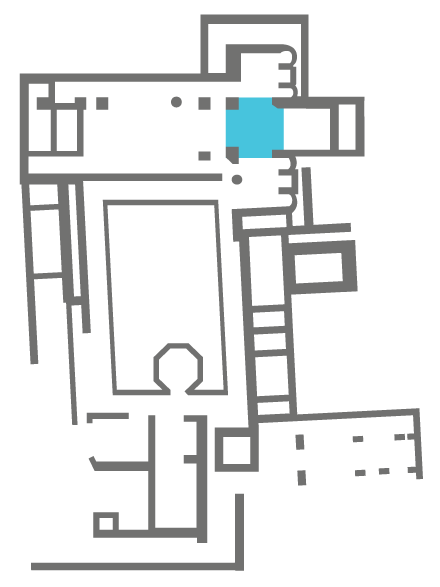

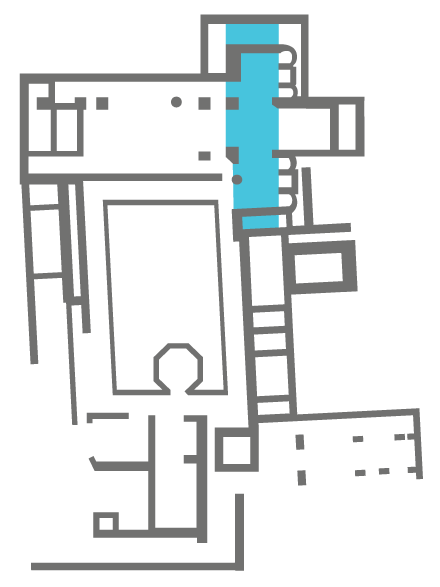

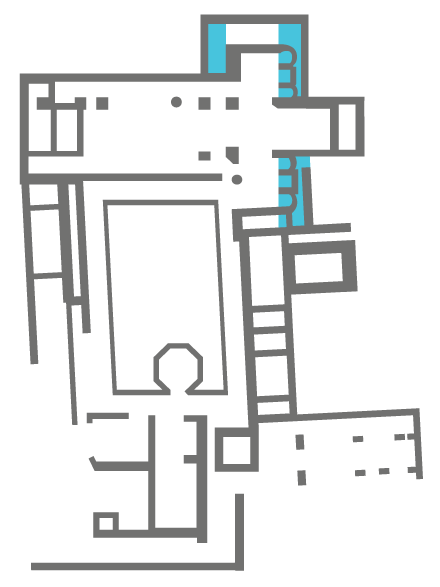

The presbytery was greatly extended in the 13th century, going from 7.63m to 13.55m in length. It was likely covered with a rib-vault. In the north wall of the presbytery are traces of two tomb recesses, between which are the remains of a doorway, perhaps the ‘porte des morts’ (door of the dead), though which the dead were carried to the cemetery following the funeral mass.

A view of the transept looking south. In the foreground of the picture can be seen the foundation walls of the original north arm of the transept, which was enlarged in the 13th century, to the north, east and west. The new transept almost doubled the size of the original, and had western and eastern aisles divided up into three chapels divided by wooden screens.

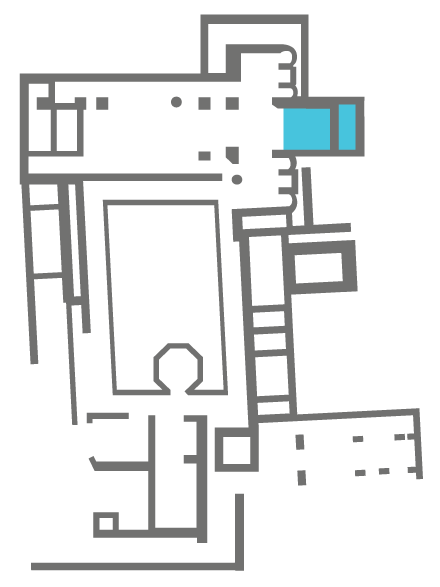

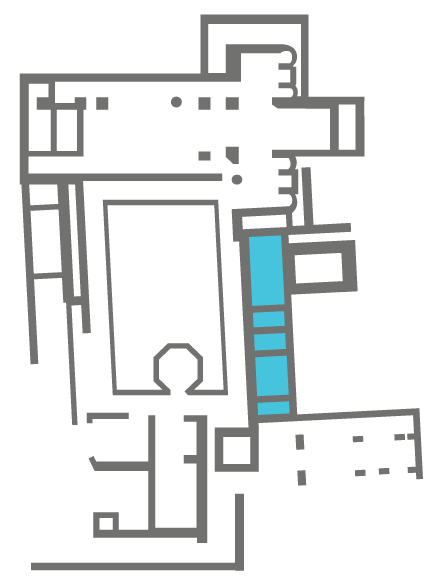

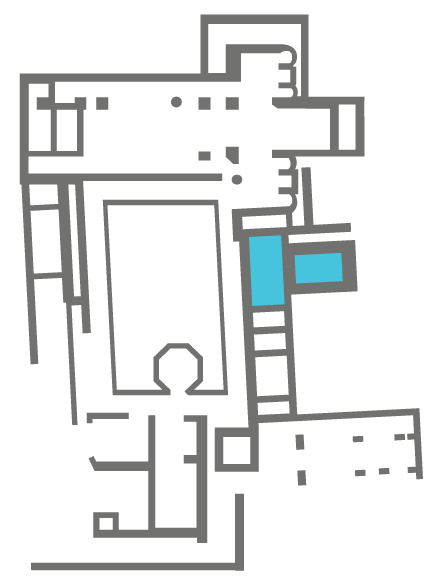

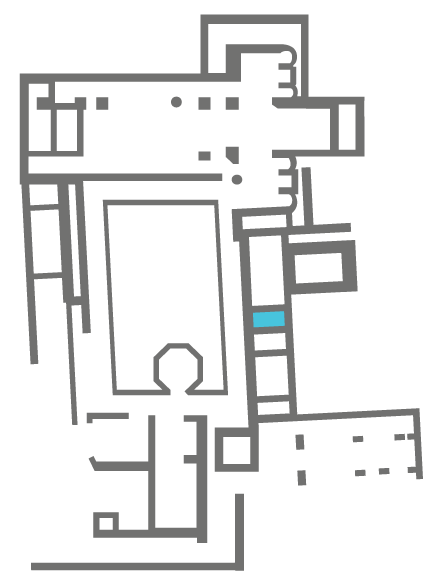

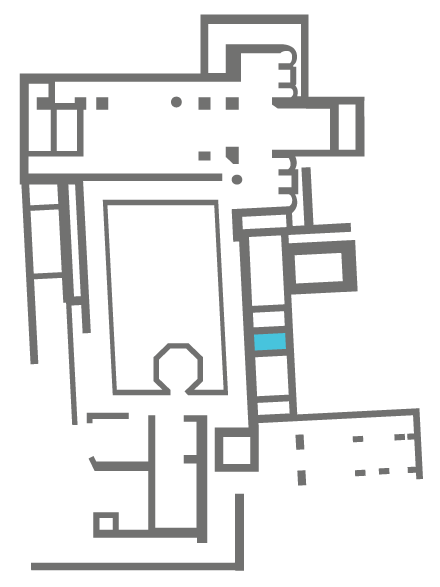

A view of the southern arm of the transept, looking towards the east range. Like the north arm of the transept, the 12th-century south transept was enlarged, though the work was made more complicated by the presence of the east range and the cloister walk, and the reconstruction was completed much later, in the 14th century. Because of the cloister walk, no western aisle and chapels could be accommodated in the south transept, making the updated plan of the church lopsided.

A view of the east chapels in the south transept, showing the foundations of the 12th-century chapels, similar to the ones in the north transept. The central chapel was square while on either side were apsidal chapel, with rounded ends.

A view of the chapels accommodated in the west aisle of the north transept when it was enlarged in the 13th century. The chapels would have been divided from each other by wooden screens.

A crypt, located underneath the twelfth-century nave at its west end, was discovered during excavations carried out in the 1950s. It is comprised of a main chamber and a small room to the north. The crypt was not vaulted, indicating that the west end of the nave had a wooden floor. In the west wall were windows and cupboards, indicating the practical purpose of the crypt though it was also structurally necessary, as on that side of the church the ground sloped towards the river.

A view of the crypt, showing the small room that was separated from the main chamber of the crypt by a doorway, and which would have been located underneath the north aisle.

The east range appears to have been arranged according to the usual Cistercian plan, with a sacristy and a chapter room, which in the 13th century was rebuilt behind the original one. Little remains of the east range and it is difficult to identify the rest of the rooms, though they probably comprised a parlour, a staircase leading to the dormitory above, and the monks’ day room beyond.

A view of the 13th-century chapter house, behind the remains of the original one. The latter was probably vaulted, perhaps like in Dunbrody Abbey, with two free-standing piers supporting rib-vaults. The new chapter house was probably used in conjunction with the older room, which thus became a sort of vestibule.

A view of the interior of the new chapter house, which is rib-vaulted, and has three windows. The north and south windows have later, 14th-century curvilinear tracery, while the tracery of the east window is gone. The capitals of the windows jambs and those supporting the ribs of the vault present an array of carvings, including foliage ornaments, grotesque heads and trumpet scallops, which allow to date the construction of the chapter house to the first quarter of the 13th century.

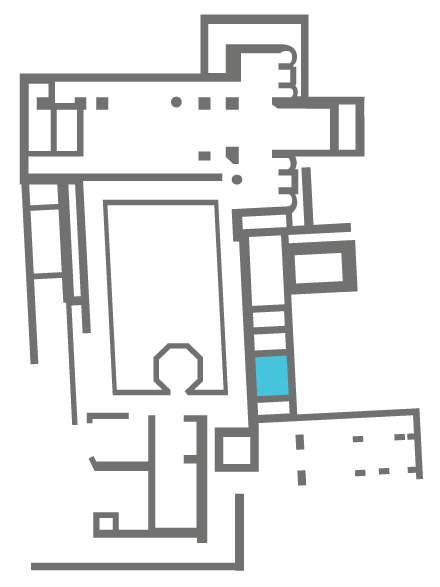

This room located directly to the east of the original chapter room might have been a parlour, where the prior might talk to monks individually and organise the day’s work.

This narrow room might have housed the staircase, or day stairs, leading up to the monks’ dormitory above the east range.

In a Cistercian context, the larger room to south end of the east range was usually the monks’ day room. It would have been vaulted and heated by a fireplace.

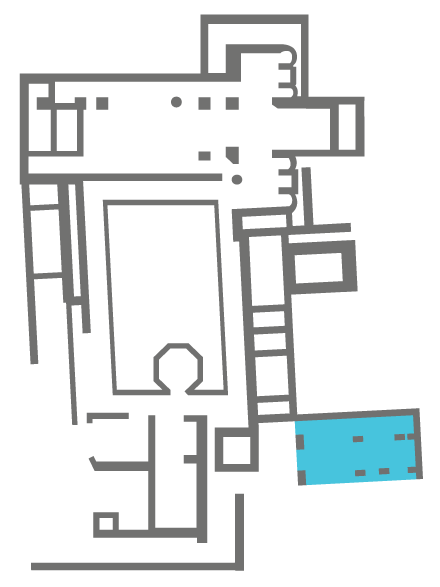

This large room projecting east from the south range appears to have been divided by piers into three aisles, though it is unclear whether the surviving sections of masonry are the remains of piers or in fact of continuous walls. It is too vast a room to have been the reredorter or latrines, and architectural historian Harold Leask has suggested it was an infirmary, though it is also possible it is post-medieval in date and belongs to the secular occupation of the abbey.

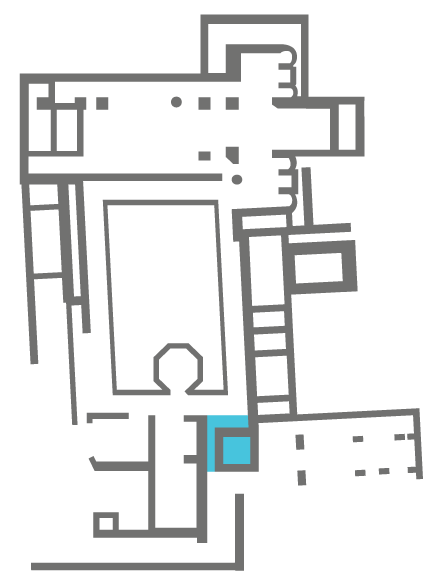

These two barrel-vaulted spaces do not seem to belong to the early phase of the abbey, but rather to its late medieval history or to the 16th-century secular occupation of the abbey. They occupy the space where the calefactory would have usually been found in Cistercian monasteries, directly to the east of the refectory.

Of the refectory, located in the centre of the south range, only the foundations remain, tracing a long rectangle with a north-south axis, which suggests it was rebuilt around or after 1200, replacing an original refectory aligned with the range, arranged around a smaller cloister. At the south end of the west wall the foundations widen where the reader’s desk was located.

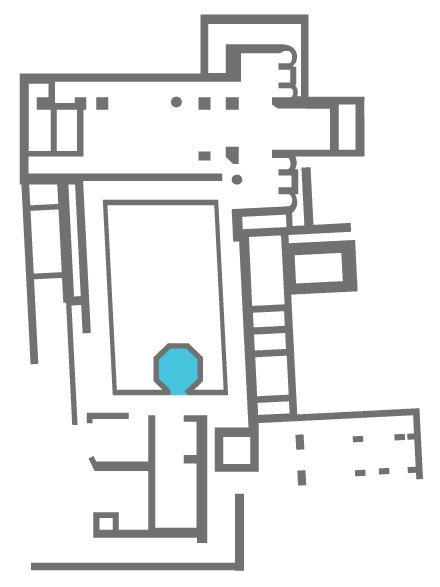

A view of the lavabo, which is widely consider the most beautiful feature of the abbey to have survived. It has an octagonal plan, and about half of the original structure remains. On each side is a richly moulded arch and capitals carved with a variety of ornaments. The upper part of the lavabo was likely remodelled by the Moore family after the Dissolution. It has been suggested they used the refectory as a hall, and the lavabo as a porch.

A view of the interior of the lavabo. It was rib-vaulted and the first few sections of the vault remain. Based on its elaborate mouldings and other stylistic features, architectural historian Roger Stalley suggested a date of around 1210 for the construction of the lavabo.

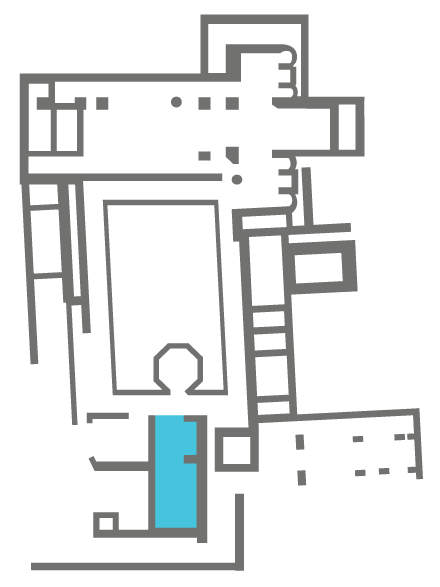

To the west of the refectory are a group of foundations which it is difficult to make sense of, but that likely represent the site of the kitchen.

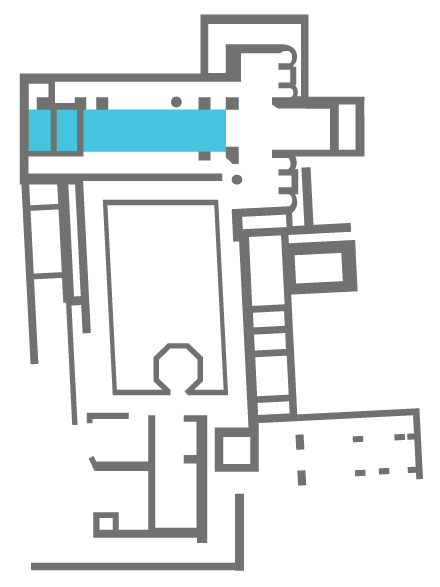

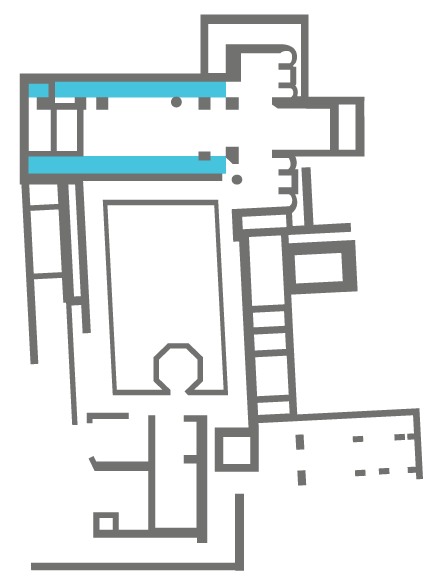

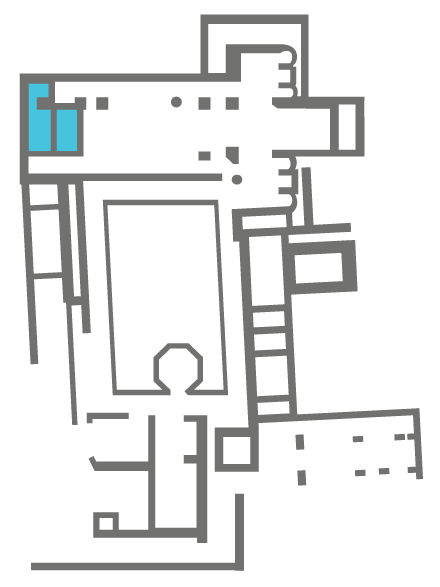

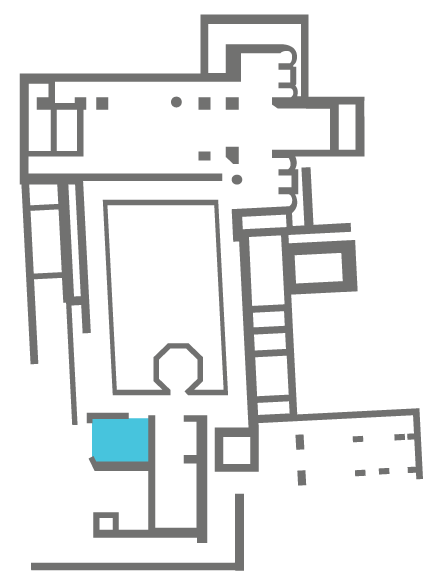

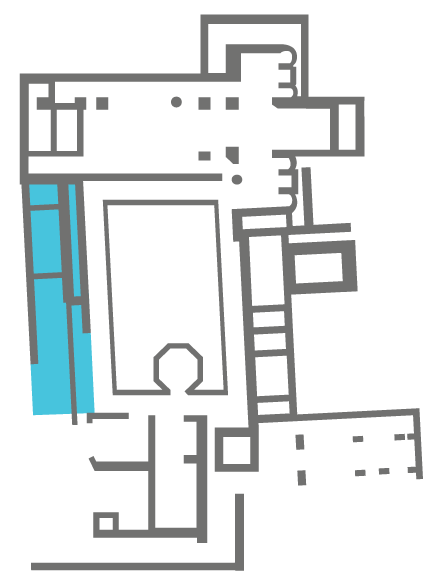

A view of the west range of the domestic buildings, where the lay brothers slept and took their meals. Their refectory would usually be located to the south end of the range, their dormitory above. The range would have also accommodated store rooms and an entrance into the monastery from the west.

Another view of the west range. Between the rooms of the range and the cloister walk is a narrow passage. This is known as the ‘ruelle des convers’ (lay brothers’ alley), common in 12th-century foundations, but often removed in later reconstructions. Its function was to provide an easy access to the rooms of the range without encroaching on the cloister, while it emphasizes the strict separation between the monks and lay brothers as underlined in Cistercian statutes.

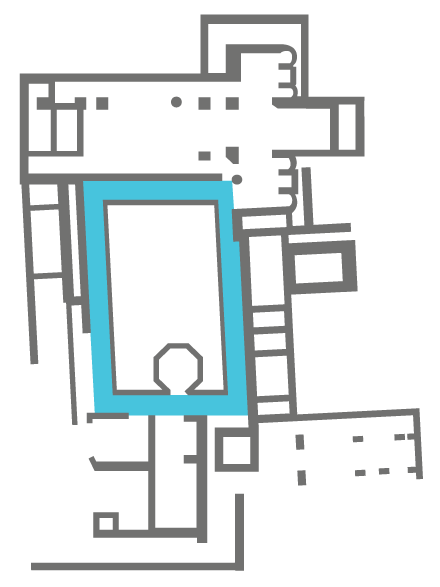

A view within the cloister garth, looking towards the Lavabo. It has been suggested that the cloister was extended to the south at some point, probably around 1200, which would explain its unusual rectangular plan. At the same time the south range was demolished and rebuilt further south, with a new refectory built along a north-south axis as shown by the remains of its foundations.

A view of the south cloister walk, featuring the section of the arcade reconstructed following the 1950s excavations. It is comprised of round arches resting on twin, slender columns with scalloped capitals, and is representative of the cloisters of many Cistercian monasteries throughout Europe. It is possible that Mellifont introduced the design to Ireland. It has been dated to the end of the 12th century, and parallels can be found at Boyle and Corcomroe abbeys.