Glendalough

Add to favorites

Add to favorites

Founded in the early 7th century – re-organised substantially in the 11th/12th centuries

Founded by St Kevin (Cóemgen)

Also known as Gleann-Dá-Locha (the valley of the two lakes)

The Place

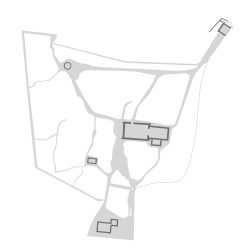

Glendalough, an extensive monastic complex, is located in a glacial valley consisting of two lakes (the Upper and Lower Lakes) which explains the Irish place name Gleann dá Locha ‘the valley of the two lakes’. This is an archaeologically and architecturally rich landscape that is matched by a wealth of historical documents. Evidence for human activity in the valley possibly goes as far back as the Neolithic Period. Recent excavations have uncovered industrial activity that may be contemporary with St Kevin’s reputed foundation of a ‘monastery’ around 600AD. Glendalough is one of the most important medieval ecclesiastical landscapes in Ireland and since the nineteenth century one of Ireland’s premier tourist attractions.

The People

St Kevin (d. 618/622AD) is reputed to have founded Glendalough in the late 6th or early 7th century as a place of retreat from the world. His name Cóemgen ‘fair birth’ and those of his close relatives, all of whom include cóem ‘fair’ in their names, suggest that the life of the real St Kevin was enhanced by adding mythology to history, as was often the case with early Irish saints. Historically, St Kevin and Glendalough belonged to the royal dynasty of Dál Messin Corb who held lands from the Wicklow Mountains to the coast. Many churches with saints of the Dál Messin Corb in the region maintained links with Glendalough to the 12th century. The medieval lives of St Kevin portray him as a hermit and a miracle-worker. A tradition of anchorites retreating from the world, possibly to the Upper Lake, was maintained in Glendalough during this early period. St Kevin’s miracles often portray him as close to nature, a characteristic described by the Anglo-Norman Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) in his description of Ireland written in the 1180s.

Glendalough was one of the main pilgrimage attractions of medieval Ireland. According to the life of St Kevin, to be buried in Glendalough was as good as being buried in Rome. Such a claim attracted the pious and the powerful and historical death notices and inscribed grave slabs record the deaths of kings, queens and ecclesiastics in Glendalough. As a centre of learning, its scholars produced manuscripts in Irish and Latin, including medieval astronomical and mathematical texts and chronicles. Pilgrims routes crossed the mountains, often marked by crosses or more elaborate markers such as the Hollywood Stone found in West Wicklow and now on display in the Glendalough Visitor Centre.

Glendalough reached its most powerful period between 1000 and 1150AD during the reigns of the Irish kings Muirchertach Ua Briain (of Munster), Diarmait mac Murchada (of Leinster) and Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair (of Connacht), all of whom had ambitions to be kings of Ireland. The most famous abbot of Glendalough Lorcán Ua Tuathail (Laurence O’Toole) became first archbishop of Dublin and died in Eu, France in 1180. All of these individuals were involved somehow in re-organizing the ecclesiastical settlement and in constructing the stone buildings that survive to the present day. Glendalough competed with Dublin and Kildare to become the most important church in Leinster and once it lost that position and was subsumed in 1215 into the Dublin diocese, it not only lost a privileged status but also its lands to new foundations such as the Augustinian foundation of Holy Trinity in Dublin.

Why visit here?

Glendalough has attracted pilgrims and visitors over many centuries for its hallowed surroundings, its traditions and its stunning scenery. A remarkable collection of ruined medieval churches is spread out over 3km along the valley. As a relatively unaltered group of up to nine Romanesque or earlier churches, it is unique in Ireland and Britain. It graveyard reflects the close ties between the church and the local community with families buried there for many generations.

Glendalough is located within the Wicklow National Park, a beautiful, largely untouched mountainous landscape of 20,000 hectares. There are a variety of hikes that you can do, ranging from a stroll around the lake to more strenuous 11km hikes. A trail guide is available from the Visitor Centre for a small charge and walking tours are run by local operators.

A 3D tour of the landscape

Click the image to explore Glendalough – a 3D Icon

What happened here?

Late 6th/Early 7th Century: The first monastery was founded at this site by St Kevin. A hermitage was located near the Upper Lake.

618 or 622: The reputed dates of St Kevin’s death.

7th to 12th centuries: The Irish annals record long lists of abbots, bishops, men of learning and other officials of Glendalough. Many of them belonged to families from the wider locality who maintained their noble status by holding onto monastic positions.

11th century: Glendalough was attacked and burned on numerous occasions. While the surviving buildings at Glendalough are stone, early churches in Ireland were generally built of perishable materials such as timber, post-and-wattle or clay until the tenth century so that while fire would have been very destructive re-building would have been relatively easy.

1085: Gilla na Náem, bishop of Glendalough died, having become a Benedictine monk in Germany and later head of the monks at Wurzburg.

1111: At the Synod of Ráth Breasail, Glendalough was named as one of the five bishoprics of Leinster.

1128: Gilla Pátraic, coarb of Coemgen (‘successor of St Kevin’) was murdered

1152: Dublin was chosen one of the four archbishoprics of Ireland at the Synod of Kells, depriving Glendalough and Kildare of their privileged status in Leinster.

1162: O’Toole was named successor to Gilla na Náem but refused the honour. He was elected archbishop of Dublin in 1162. He died in Eu in Normandy in 1180 and was canonised in 1225.

1213: King John I of England made a grant of all the bishopric of Glendalough to the archbishop of Dublin. It was confirmed by Pope Innocent III in 1216, resulting in Glendalough becoming an archdeaconry in the diocese of Dublin and no longer a bishopric.

1398: Glendalough was burnt by the English.

15th century: As the English colony around the Pale lost territory in and around the Wicklow Mountains, attempts were made to revive the bishopric of Glendalough. A Dominican named Denis White held the title of Bishop of Glendalough from 1481 until 1497 when he made a formal renunciation of his rights in Dublin.

17th century: All the churches were in ruin and roofless when visited after the Dissolution.

Up to 19th century: Glendalough was still in use for its Pattern Day(patron saint’s day) celebrations and pilgrimages on 3rd June, St Kevin’s feast day. In 1862, this practice was ended by Cardinal Cullen, archbishop of Dublin (d. 1878) due to the superstitious practices of the pilgrims and the disreputable secular elements.

“The Patron (The Festival of Saint Kevin at the Seven Churches, Glendalough)” by Joseph Peacock (c.1783–1837), Ulster Museum (Image credit: National Museums Northern Ireland)

An account of the Pattern Day at Glendalough in 1779 by Gabriel Beranger paints quite a scene!

People “often spent a large portion of the night walking among the ruins, where an immense crowd usually had bivouaced [camped] … throughout the space of the sacred enclosure. As soon as daylight dawned, the tumbling torrent over the rocks and stones of the Glendasan river to the north of the churches became crowded with penitents wading, walking, and kneeling up St. Kevin’s Keeve, many of them holding little children in their arms … The guides arranged the penitential routes, or conducted tourists round the ruins …

Dancing, drinking, thimble-rigging, prick-o’-the-loop, and other amusements, even while the bare-headed venerable pilgrims, and bare-kneed voteens were going their prescribed rounds, continued…

Towards evening the fun became fast and furious; the pilgrimages ceased, the dancing was arrested, the pipers and fiddlers escaped to places of security, the keepers of tents and booths looked to their gear, the crowd thickened, the brandishing of sticks, the ” hoshings” and ” wheelings,” and “hieings” for their respective parties showed that the faction fight was about to commence among the tombstones and monuments, and that all religious observances, and even refreshments were at an end…”

From the Memoir of Gabriel Beranger, and His Labours in the Cause of Irish Art, Literature, and Antiquities from 1760 to 1780, edited by William Wilde (1873)