A view of the abbey, from the bridge spanning the Tintern River to the south. The woodlands around the abbey and the estuary of the River are important nature reserves.

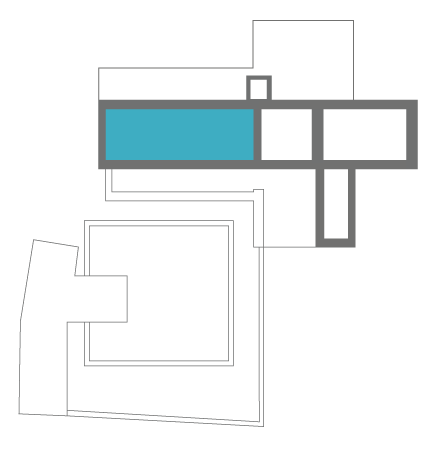

A view of the abbey church as it appears today, looking north at the Lady Chapel and chancel. The precinct walls and entrance seen here date to the later development of the Colclough residence in the nineteenth century, when the church nave was converted into a three-storey neo-Gothic house.

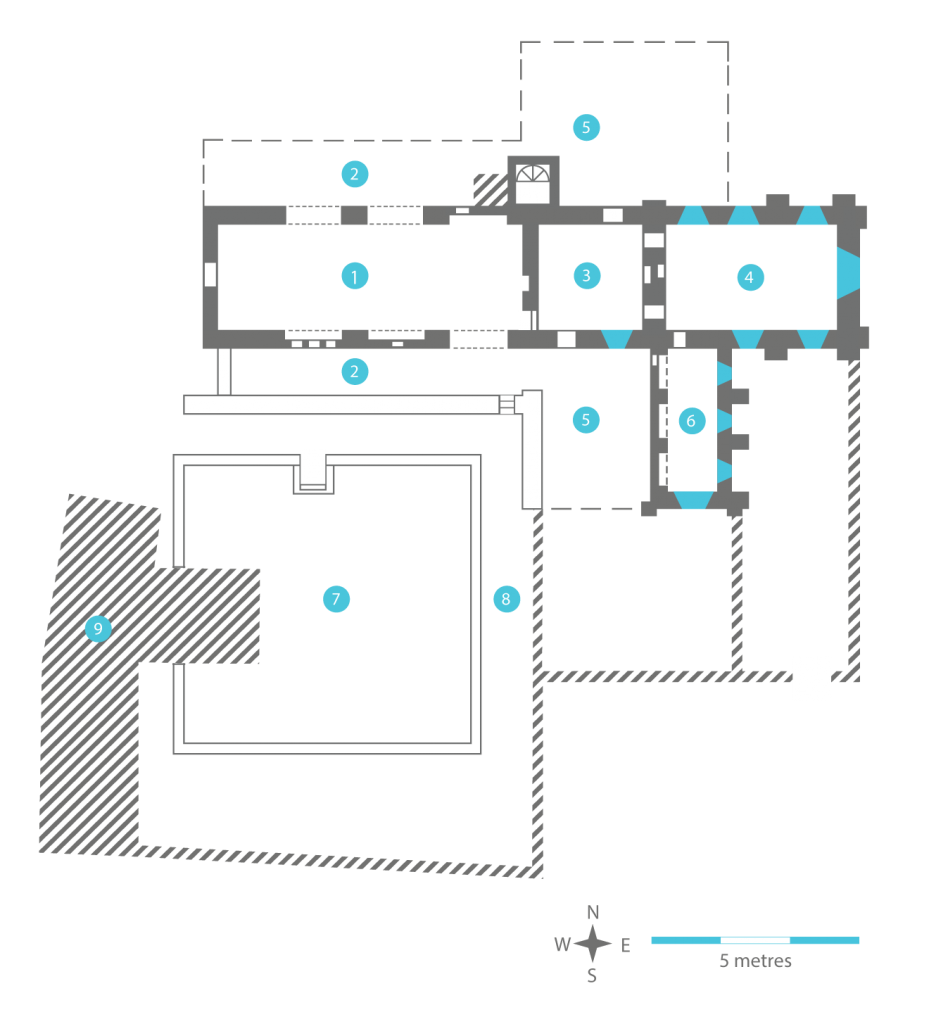

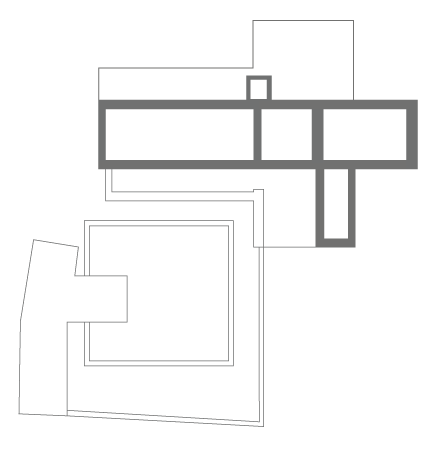

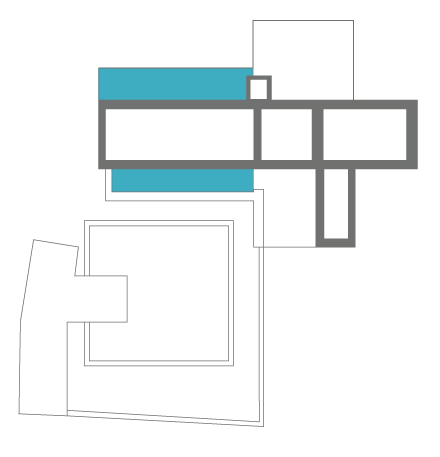

The west doorway was blocked up when the Colclough converted the abbey into a domestic dwelling, and windows were inserted. The original 13th-century doorway was revealed in the 1960s after the modifications were removed. Nothing remains of the window above, though it would have been quite large at four metres wide. It is possible the nave was never built as long as originally intended - explaining why the cloister projected unusually far beyond the west end of the church.

The 13th-century nave is very plain in design, with unmoulded arches and piers. There was a clerestory (upper level) above the arches, which does not survive. The nave was converted into a three-storey house of Georgian Gothic style by the Colclough family in the nineteenth century. During excavations carried out in 1982/83, 32 burials were uncovered in the nave, likely dating to the 15th and 16th century, in the years of decline that preceded the Dissolution.

These pointed doorway and windows are remains from the Colclough’s conversion of the nave in the nineteenth century. It was the main entrance to the house. They blocked all six arches dividing up the nave from the lateral aisles and inserted neo-Gothic windows.

A view of the site of the north aisle of the church. Excavations and historical references have indicated that it was demolished, along with the north transept arm, during a remodelling of the church in the middle of the 15th century, reducing the size of the church dramatically. The Colclough further blocked the arches during their conversion.

The south aisle was also abandoned in the 15th century, and the Colclough used the west-most arch as the main entrance to their new house in its last development in the nineteenth century. At the east end of the south aisle was located the main entrance into the church for the monks, the ‘processional doorway’.

The tower is square in plan and is 27m high, including the crenellations, which were likely a 15th-century addition, later repaired by the Colcloughs. From the large stone corbels that survive inside the tower, it appears that the crossing was not vaulted, but timber-roofed. Access to the upper floors of the tower is provided by a spiral stairs in the turret projecting off the north wall of the tower, the entrance to which is through a small porch. Both turret and porch might date to the 15th-century re-modelling of the church.

The abbey crossing tower, looking south. Towers were added from the 13th century onwards to existing Cistercian abbey churches, but in Tintern it was integral to the original plan – though it might have been built later on – making it one of the few early examples of such towers to survive.

The interior of the crossing tower, showing the last two upper floors, the floors of which are gone. Anthony Colclough began to convert the tower into a fortified house in the second half of the 16th century, blocking up the arches on its four sides and installing five upper floors with timber floors and limestone fireplaces on the first three. He used local oak trees felled in 1569/1570, and reused the timber from the monastic buildings for the cross beams and window lintels.

A look at the Elizabethan wattle (woven wooden sticks) and daub (mud) timber frame screen which was plastered over and used as a dividing wall in one of the upper floors of the tower when it was converted into a fortified residence in the late 16th/ early 17th century.

The north elevation of the chancel showing the shallow buttresses that strengthened the walls, connected by a row of corbels (called a corbel table) carved into grotesque human, monstrous, or hybrid heads. In the late 16th century, Anthony Colclough converted the chancel into an extension to his newly developed tower house, inserting Tudor-style triple-light windows within the medieval lancets. The chancel was abandoned as a dwelling in the early 19th century, and most of it then became an open yard.

A closer look at some of the grotesque heads decorating the corbel table running along the top of the chancel walls. The only other example of such feature in a Cistercian context in Ireland can be found in Grey Abbey (Co. Down).

A view of the east gable of the chancel. The very large original window was replaced by a narrower one, perhaps during the 15th-century remodelling of the church. There is no trace of the tracery that once filled the window, but the springing of the moulding on the outside is decorated with foliage ornament. On the inside of the window are three small sculpted figures of ecclesiastics and a carved head.

The southern arm of the transept was demolished after the Dissolution, with only its eastern chapels – also known as the Lady Chapel –preserved. 18 burials were excavated in the area of the south transept, dating to the late 15th and early 16th century.

Nothing remains of the north arm of the transept above ground, but when 19th-century buildings abutting the church were removed the wall scar left by the transept east chapels was revealed, although excavations did not uncover any foundations for the transept or for the aisle. The north transept was likely destroyed when reconstructions took place in the mid-15th century, and the stair turret was added to the north of the tower.

The Lady Chapel, which represented the eastern aisle of the south transept, was preserved after the Dissolution. At ground level it is divided into three rib-vaulted bays (sections). In the late 16th century, two storeys were added to the chapel, at the same time the chancel was being converted. The upper room, with its large traceried window seen here in the south façade, was later used as a library by the Colcloughs.

A view of the restored interior of the Lady Chapel, showing the rib-vaulting with key stones carved into rosettes (round, stylized flower designs).

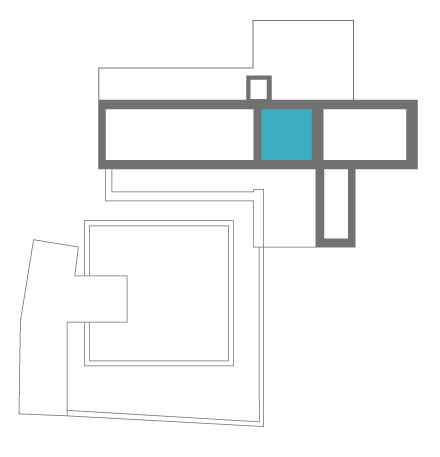

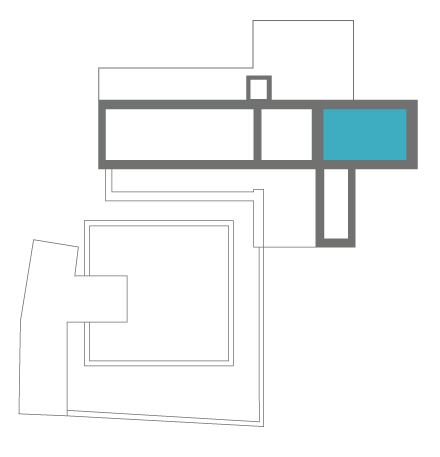

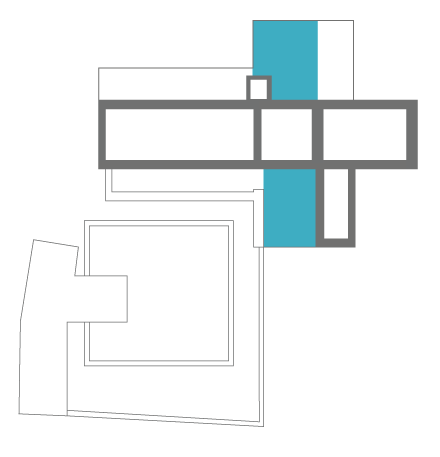

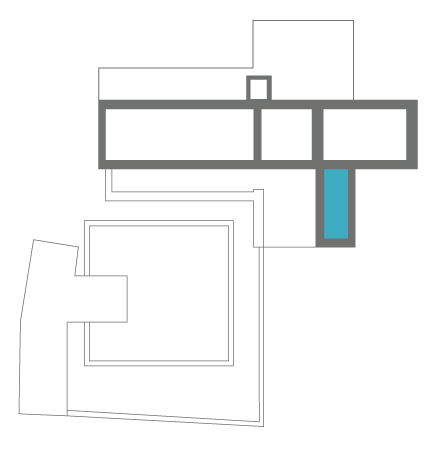

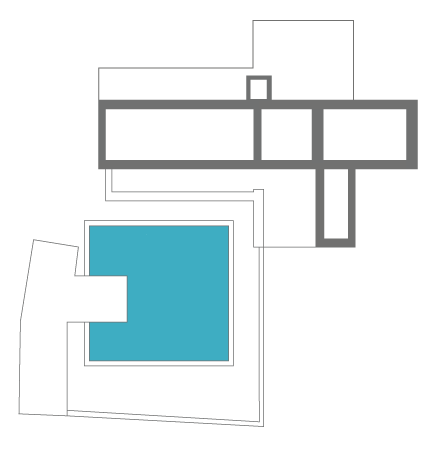

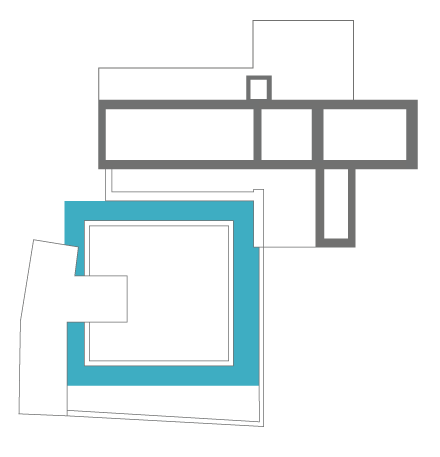

Almost nothing remains of the cloister and domestic buildings of the abbey, which were thoroughly taken down following the Dissolution. During excavations however, 16th century demolition debris recovered from the cloister walk included fragments that allowed a reconstruction of what the cloister arcade would have looks like. It was comprised of round arches resting on twin columns with bases and capitals, a widespread design in a Cistercian context, and was dated to the first half of the 13th century.

Another view of the cloister garth, showing the remains of the collation bay, used during the Collation ceremony, which took place after Vespers. The monks would gather in the walk closest to the church and listen to a reading, before processing back into the church for Compline. The reader took place in front of a lectern set in the collation bay. Opposite the reader along the church south wall were the abbot’s seat and the collation bench, where the community sat down to listen to the reading.

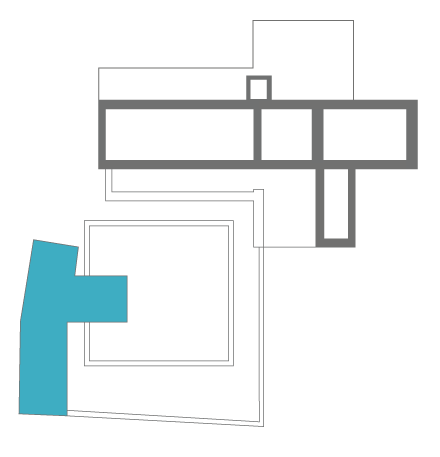

A view of the east side of the cloister walk (or ambulatory). Only the west side of the cloister walk was excavated below floor level, and burials were found - it is surmised that all four sides were used for burials. Nothing remains of the east and south ranges of the abbey’s domestic buildings. However, the remains of the monastic drain that ran below the monks’ reredorter were excavated, showing that the east range originally extended well beyond the south range; but in the early 14th century the reredorter and southern end of the dormitory were taken down.

Today, the visitors’ facilities are housed in the 18th or 19th century stables that themselves incorporated the medieval cloister gateway and some adjacent structures. These are the only standing remains of the abbey’s domestic buildings that once surrounded its cloister.