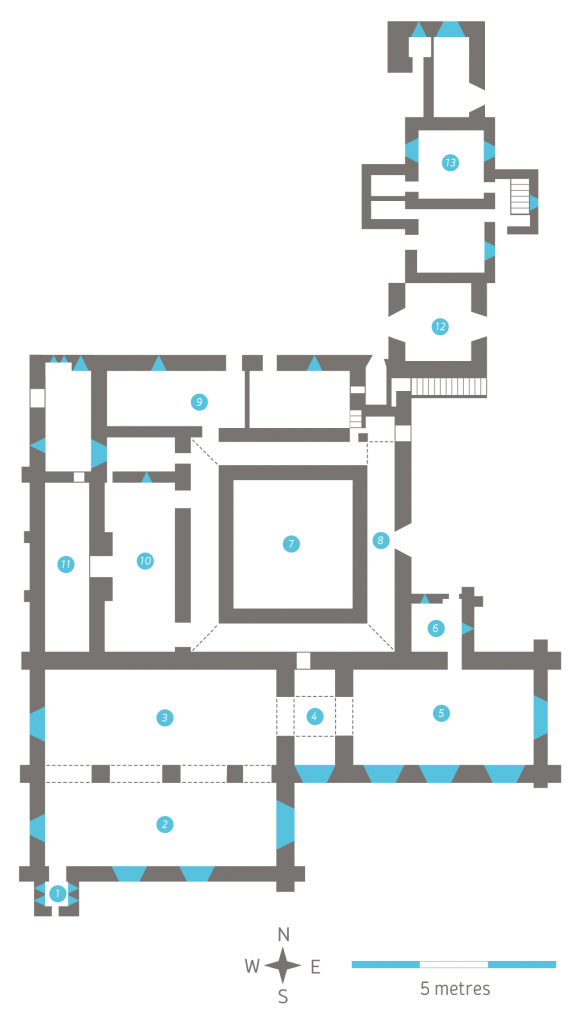

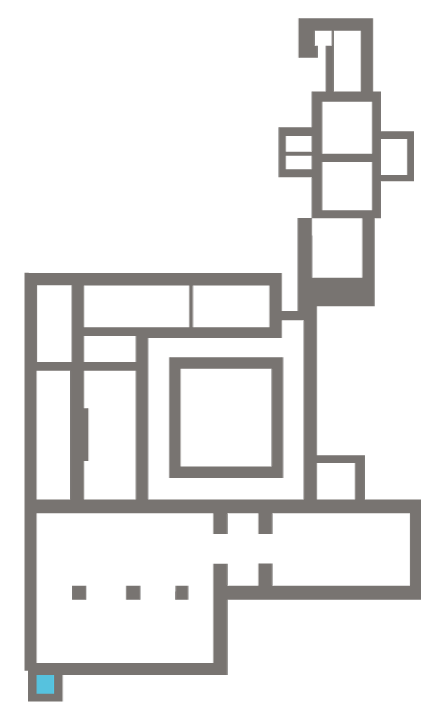

A view of the modern vestibule, which was added to the church southern elevation when it was restored for worship in the nineteenth century, and through which the nave and its lateral aisle are now accessed.

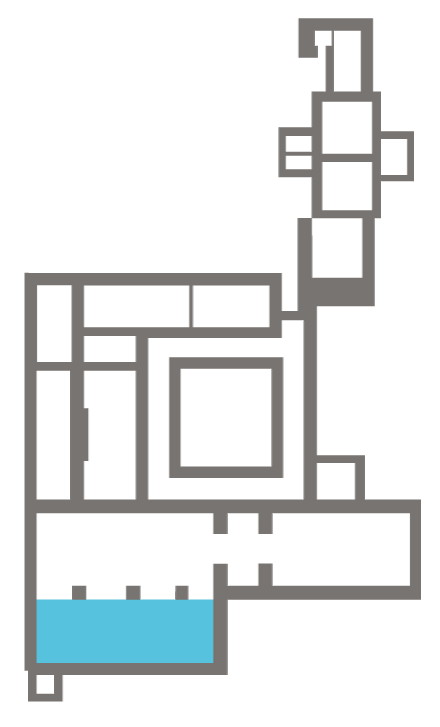

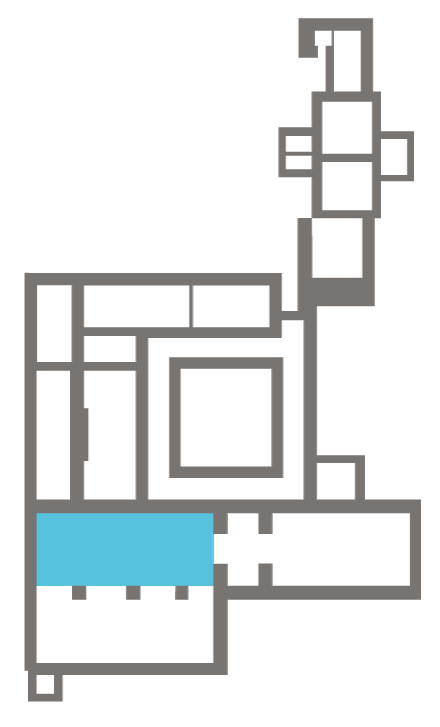

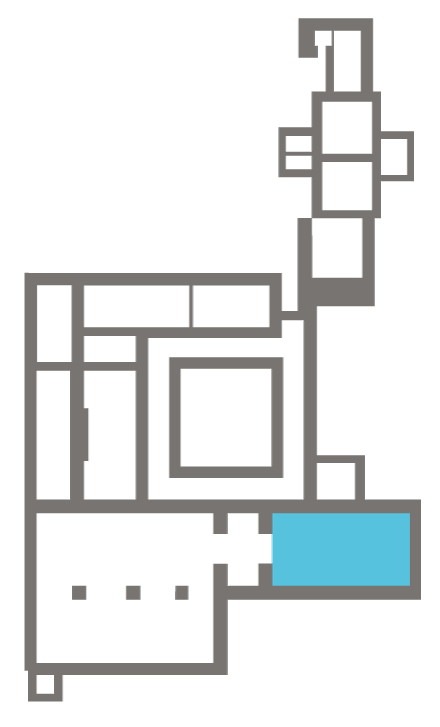

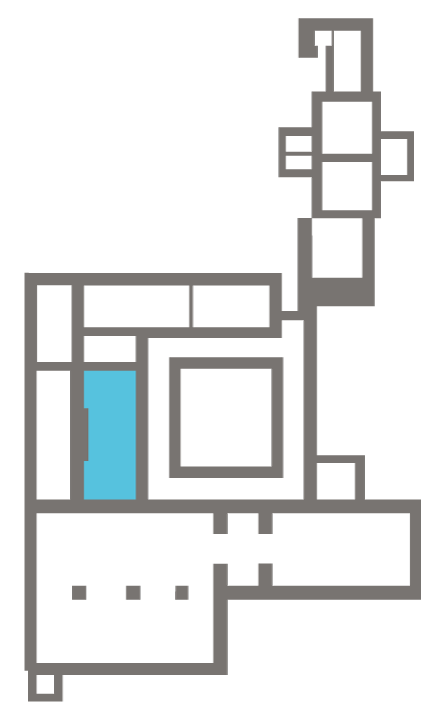

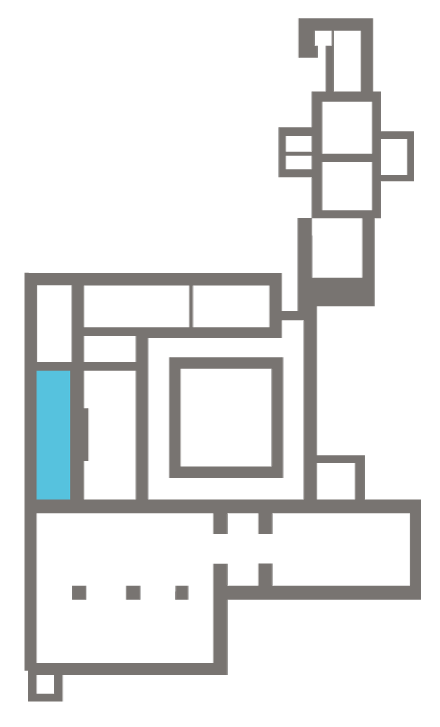

A view of the nave lateral aisle, Which doubled the space where the congregation gathered, where chantry chapels and secondary altars could be funded by benefactors and where they could choose to be buried.

The south elevation of the nave lateral aisle, showing the string course running along the wall above the windows, and which is decorated with a number of carvings, including stylised flowers and grotesque figures

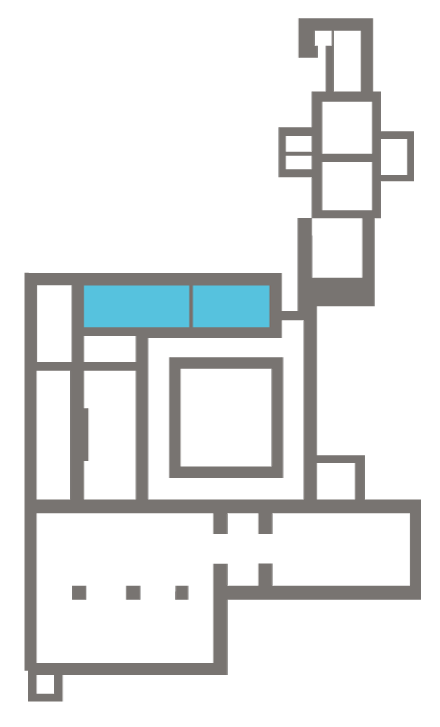

A view of the interior of the nave. When the church was restored for Protestant worship in the nineteenth century, efforts were made to keep as much as the medieval fabric as possible, as well as the medieval internal configuration of the ecclesiastical space, with the congregation gathering in the nave, separated from the chancel by the central tower, with only a limited view of the high altar through the tower arches. However, there is another altar and a pulpit at the east end of the nave, where most masses are probably celebrated today.

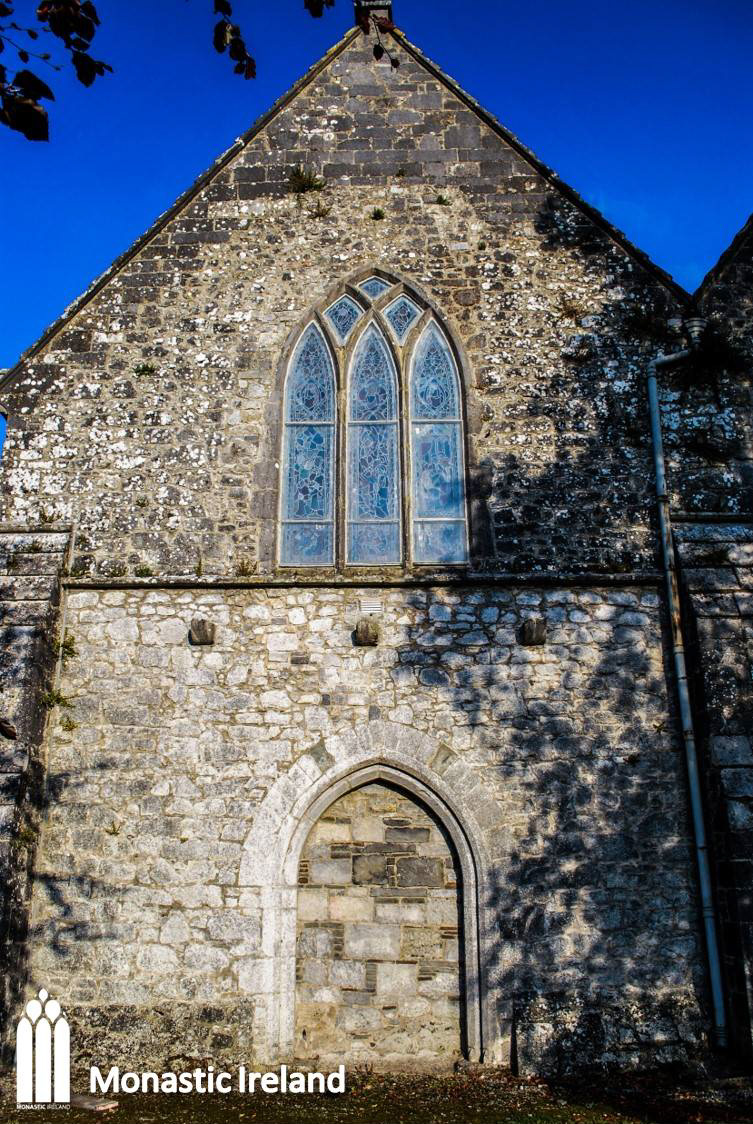

The west façade of the church, showing the blocked doorway that was the original access into the nave for the laity in the Middle Ages.

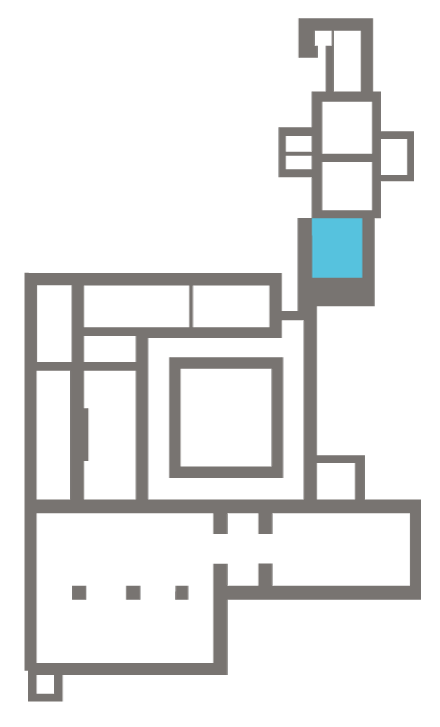

A view of the back of the friary and of the Dunraven mausoleum, which was inserted where the west range of the priory domestic buildings used to stand, between the north range and the church. It was designed by James Pain in 1826-27 and commissioned by the Earl of Dunraven, for the remains of his father and for Quin family of Adare.

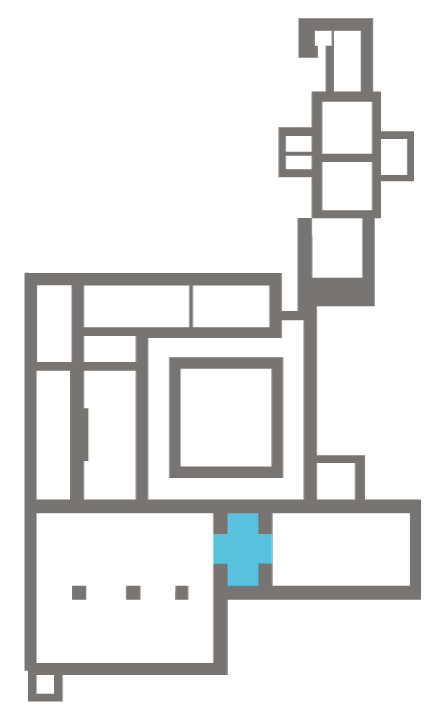

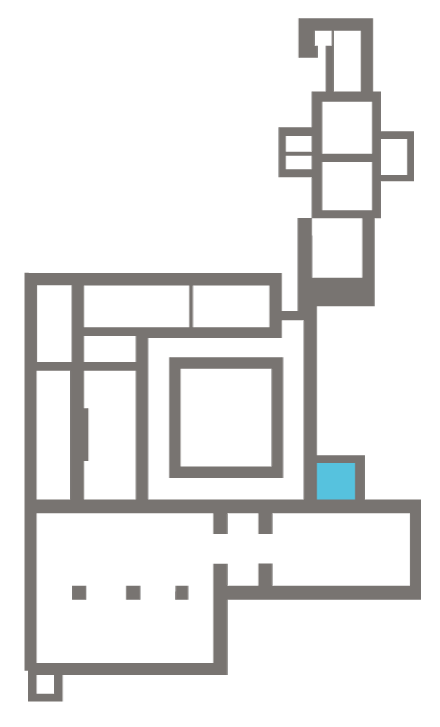

A view of the space under the central tower, looking towards the chancel. Though the access is now blocked, there was originally a doorway connecting the cloister walk and the tower, which would have been the friars’ main access into the chancel.

Three sedilia, where the officing friars would have sat during a service. Its position underneath the crossing tower is unusual, and indicates that a secondary altar, perhaps reserved for private masses celebrated for particular patrons, might have been placed there.

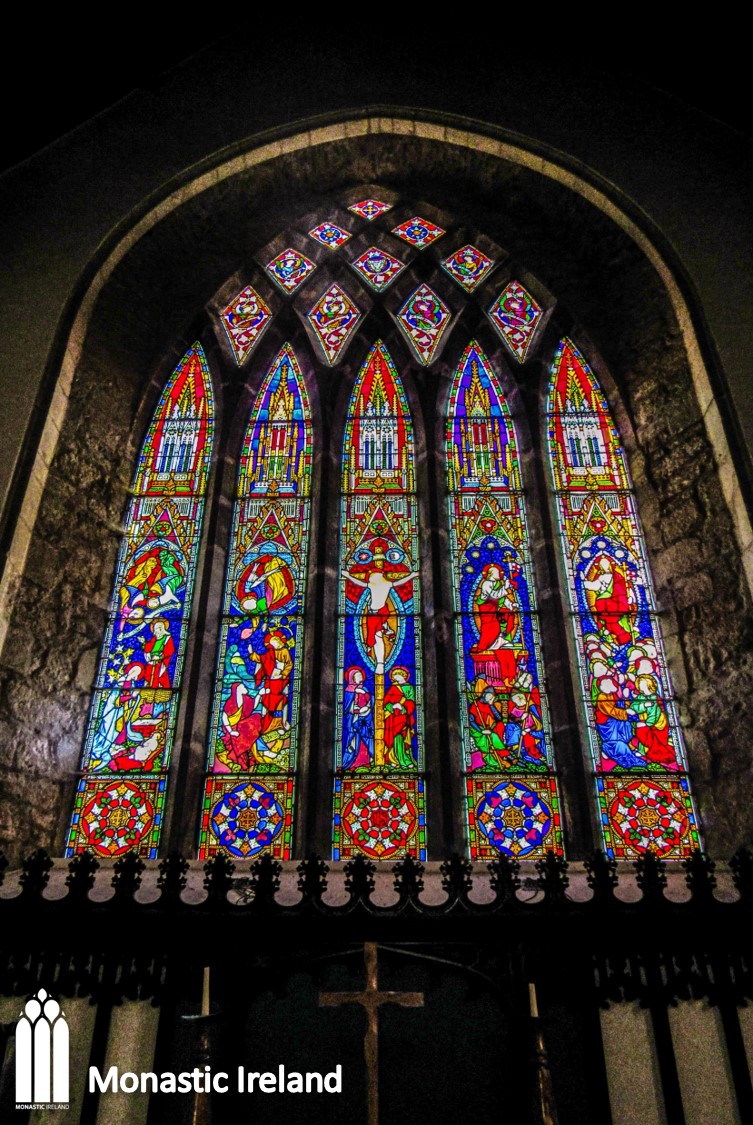

A view of the east window of the church in the chancel. It is a pointed five-lights with switch-line tracery, and dates back to the fourteenth century. Along with the entire church it was restored in the early nineteenth century, and new stained glass was fitted.

A view of the interior of the chancel. The nineteenth-century restoration kept what would have likely been the medieval ecclesiastical division of space, with choir stalls set against the walls, the presbytery separated from that space by a couple of steps and the high altar under the large east window. With its plastered walls and wooden roof, this church gives visitors a good idea of how a medieval mendicant church might have looked like, in contrast with the roofless and empty ruins of friaries that are usually encountered.

A view of the east and south elevation of the church, showing the east windows of the nave lateral aisle and of the chancel. Both date to the fourteenth century, and present switch-line tracery typical of late medieval Irish architecture. The church was restored in the nineteenth century and is now the Church of Ireland parish church of St Nicholas.

Two tomb niches (or enfeux), placed in the north wall of the church choir, close to the east end. Important benefactors of the friary would have been buried here.

Two windows in the south wall of the church choir, both pointed three-lights presenting examples of switch-line tracery. Like the entire church they date back to the fourteenth century, and were restored in the early nineteenth century when the church was used by the Church of Ireland parishioners of Adare.

A view of the friary looking west. To the left of the picture, abutting the chancel of the church is the sacristy or vestry. The doorway at the centre of the picture now leads directly into the cloister walk, but the east range of the friary once stood directly in front of it.

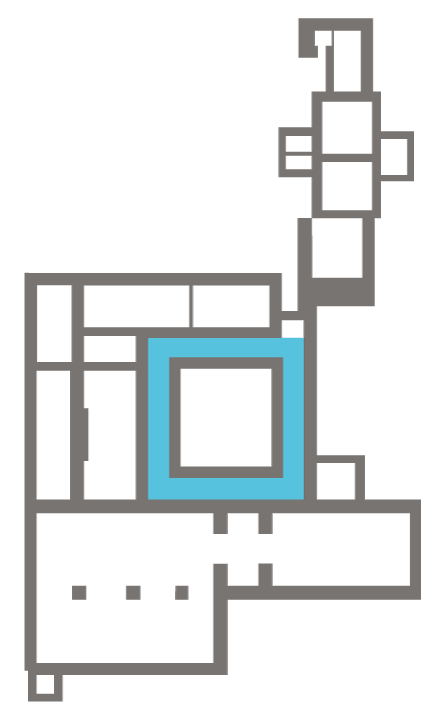

A view of the west arcade of the fifteenth-century cloister square. Behind it stands the Quin family mausoleum, inserted in the nineteenth century just behind the court where the west range used to stand.

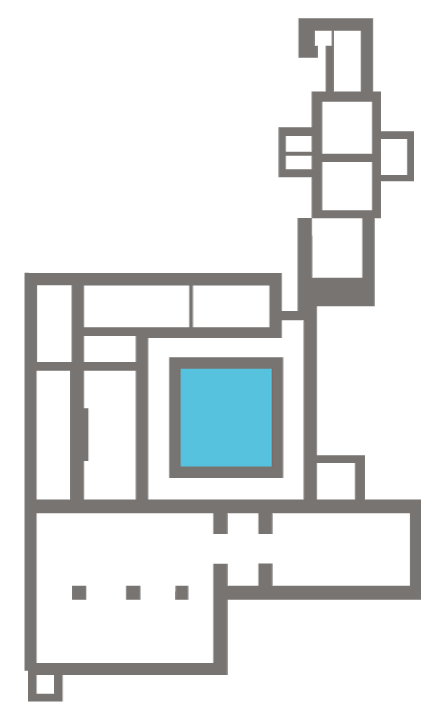

A view of the cloister square from inside the vaulted ambulatory, and a closer look at one set of the cinquefoil arches which made up the cloister arcade, decorated with escutcheons of English crosses.

A view of the interior of the vaulted ambulatory of the cloister arcade. The doorway in the south wall led directly under the tower, giving access to the friars into the chancel.

This carving of a crowned and bearded head is placed at the stop of the square hood-moulding framing the current entrance into the cloister.

The east façade of the north range of the friary’s domestic buildings. It housed the refectory in its upper floor, which was restored and opened as a primary school, St Nicholas, in 1814. In 2008, the school was moved to modern buildings behind the friary. The old school had two classrooms divided by a partition wall, and the old building is now used for PE and drama classes.

The court between the Dunraven Mausoleum to the west and the cloister walk to the east is where the west range of the friary used to stand. The building to the north would have been part of this range, and was restored as part of St Nicholas primary school, which opened in the nineteenth century.

A view of the back of the friary and of the Dunraven mausoleum, which was inserted behind where the west range of the domestic buildings used to stand, between the north range and the church. It was designed by James Pain in 1826-27 and commissioned by the Earl of Dunraven for the remains of his father and for the Quin family of Adare.

A view of the friary’s fifteenth-century gateway, which bears the arms of the friary’s benefactors, the Fitzgeralds of Kildare and Desmond. It led into the garden of the friary and from there visitors would have been received and if allowed, led into the claustral ranges. To the north of this gate are modern buildings dating to the nineteenth century and used as a private residence.